Album of the Week, March 7, 2026

Looking back at Peter Gabriel’s career, some of the consistent themes are perfectionism and painstaking deliberation. We’re talking about a performer who went from 2002 (Up) until 2023 (I/O) — 21 years between releases of original music. (There was other music of merit in that period, but that’s a different story.) So it comes as a surprise to realize that Peter Gabriel’s second album was released only 15 months after his first. Almost all of that is due to his choice of producer for the second album: Robert Fripp.

Fripp was starting to transition in his career from sideman (most notably for David Bowie on “Heroes”) and leader of the intermittently active King Crimson to producer, on the strength of his ingenious guitar work and technological inventiveness (the unique “Frippertronics” system, the first live looping solution for performers, is the best known example). Peter was looking for a specific sound texture, and brought musicians to the record who could provide it, like the redoubtable Tony Levin, drummer Jerry Marotta, and synth player Larry Fast, all of whom would appear in more PG albums. He also admired Fripp’s more improvisational and brisk working methods; he’s said about the album, “Robert Fripp was very keen to try speeding up my recording process, as many people have been since and failed, but he got closest to it.”

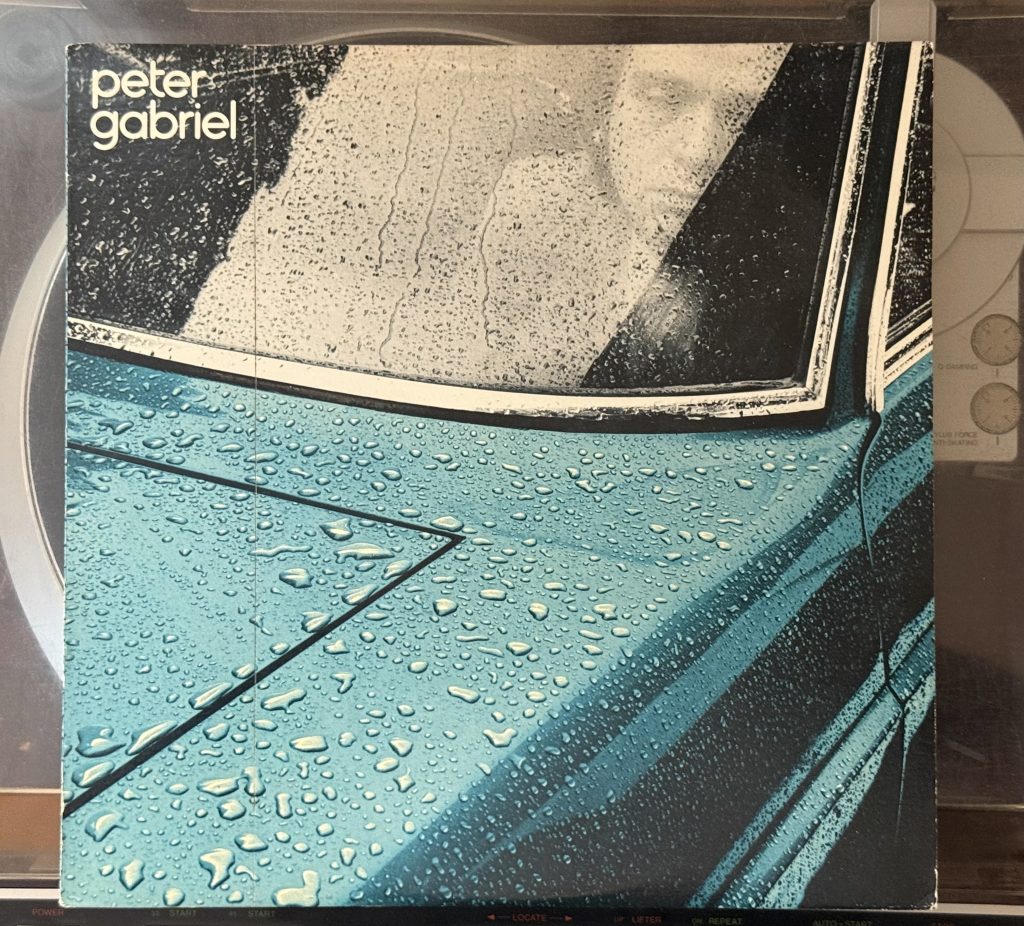

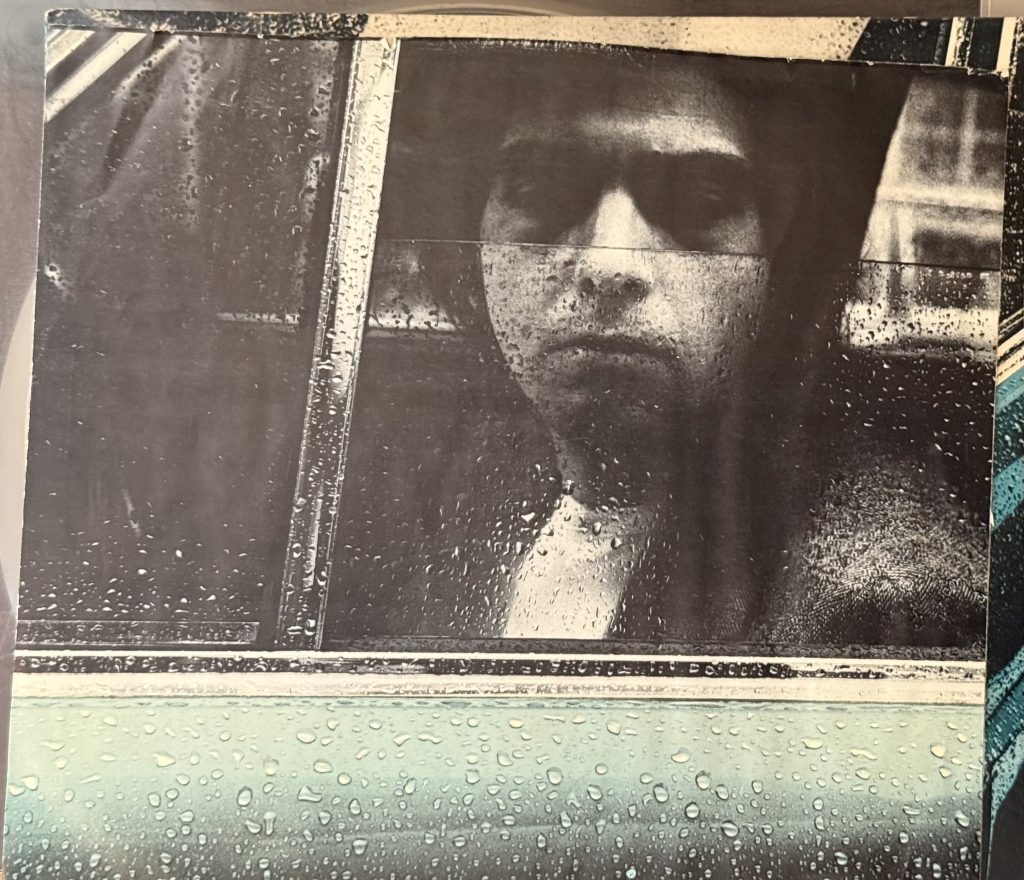

Unusually, the album is the second to be titled Peter Gabriel; Gabriel felt this allowed more attention to be paid to the album artwork by design house Hipgnosis (who also shot the “rainy windshield” on Peter Gabriel (1977)). I’ve also read that he thought of it almost like a magazine or periodical—“here’s the latest Peter Gabriel.” Looking at the entire discography, it’s clear he was never much of a fan of album titles, as we’ll see.

“On the Air” starts in a very different sonic landscape from where PG1 left off. Bright synthesizer lines lead to muscular guitar and bass, backed up by the massive drums of Jerry Marotta. The song is a straightforwardly driving 4/4 until the chorus, which drops into 6/8 for a few bars. And the vocals, while rough—you can hear the strain in his high notes, and his sometimes sandy tenor sounds thin and scratchy—are exciting, especially as he soars up the lines of “on the air” in the chorus. Lyrically, the subject—Gabriel’s Mozo character building a radio transmitter so that he can project his psychic energy out to the world—is obscure but the writing is taut: “Built in the belly of junk by the river my cabin stands/Made from the trash, I dug off the heap with my own fair hands/Every night I’m back at the shack and I’m sure no one else is there/I’m putting the aerial up so I can go out on the air.”

“D.I.Y.,” driven by a throbbing Tony Levin line on the Chapman Stick, is even more tautly wound. Gabriel says he was listening to punk and new wave at this time, and this song shows the influence even though it’s in 5/4 and has a complex chord change in the pre-chorus. It’s another song dealing with the aftermath of his time in Genesis: “You’re still looking for the resurrection/Come up to me with your ‘What did you say?’/And I’ll tell you, straight in the eye.” It’s short and pointed and a great song.

“Mother of Violence” is the only song in Peter’s work with a writing credit by his then-wife Jill. It’s a quiet tune with unusual instrumentation—pedal steel, acoustic piano—and a vocal that sounds a bit like late-1970s Phil Collins and ends with vocalese. It’s all in service of a lyric about difficult family relationships that is one of the more fraught bits of writing on the album.

“A Wonderful Day in a One-Way World” is an odd bit of a song, with a vocal that sounds a bit like a scratch take and a slightly proggy reggae feel, and a lyric that is reminiscent of some of the odder corners of Paul Simon, particularly in the dialog with the old man in the second verse. But it also has some of the better vocal harmonies on the album in the chorus, so that’s something in its favor at least. It’s followed with the frustratingly opaque “White Shadow,” which marries an instrumental track that could have been at home on late-1970s Genesis, circa …And Then There Were Three…. The first verse starts promisingly enough—“Ten coaches roll into the dust/Chrome windows turned to rust”—but then we’re rhyming “spirit died” with “Kentucky Fried.” Fripp’s guitar solo at the end is a thing of beauty, though, in duet with Tony Levin’s increasingly virtuosic bass, and there are hints of a synthesizer sound played by Peter that would become an increasingly familiar backdrop in his other albums.

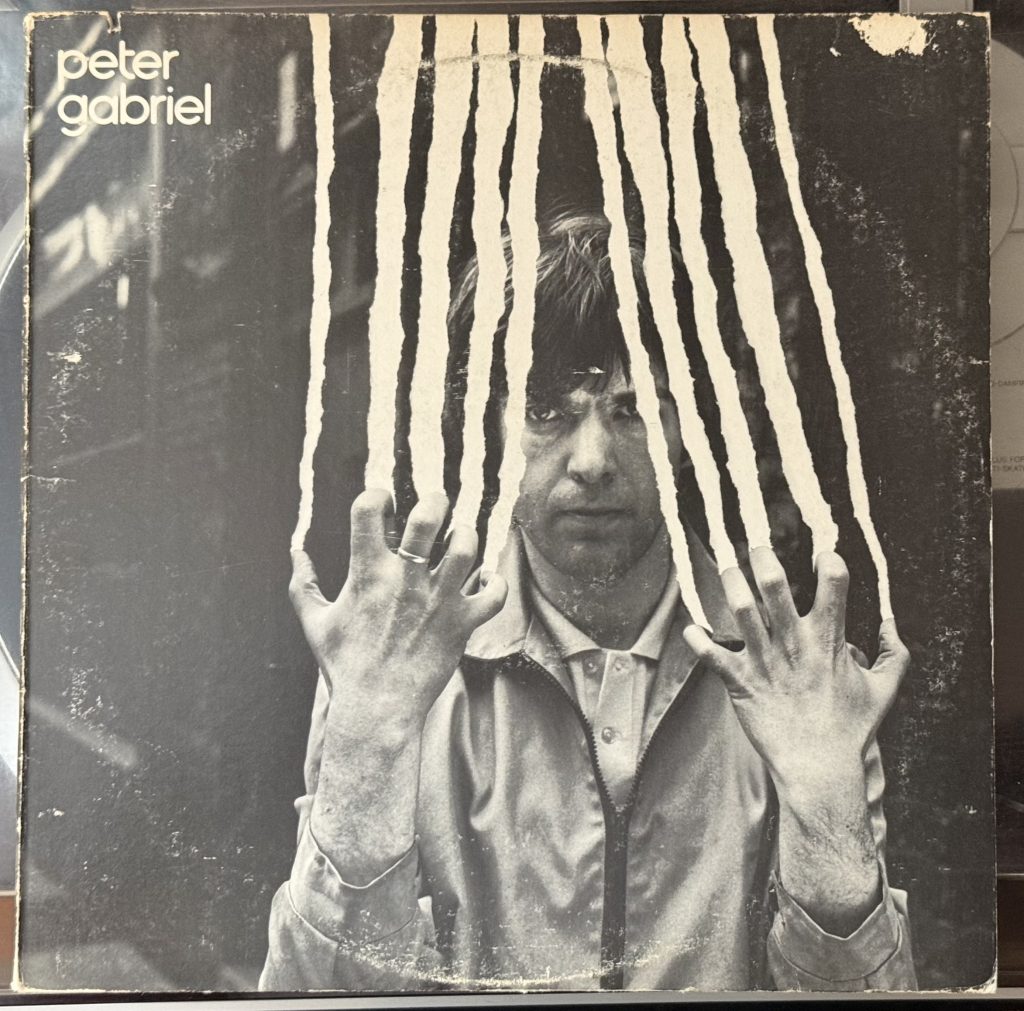

“Indigo” is a piano-driven ballad with recorder and pedal steel, a story of an elderly man coming to terms with his impending death. The track seems to have a bunch of different ideas that never quite cohere, but the vocal is one of the finer on the album technically, with properly prepared high notes and controlled dynamics adding to the emotional affect. That’s a contrast with “Animal Magic,” which has one of the rougher vocals on the album and a lyric about proving manhood by becoming a soldier, and an anonymous guitar solo that sounds a bit like generic ’70s rock.

“Exposure,” though, is one of the key sonic pieces on the album. Driven by a mean locked in groove from Levin and Marotta, the main event here is the Frippertronics and Peter’s repeated chants of “exposure… space is what I need…” It’s the groove, though, that feels the most like a Peter Gabriel song, and we’ll hear it again in many other contexts.

“Flotsam and Jetsam” is a song of lament for a failed relationship. It’s competently written but ultimately forgettable, thanks in part to indifferent vocal recording featuring one of the few instances of an echo or reverb on the album which only serves to underscore the brevity of the song. Peter seems rather in a hurry to get on to “Perspective,” which feels a bit like a downtown 1970s New York number complete with saxophone on the chorus and a repeated “I need perspective” on the verses. Gabriel sings from the perspective of an industrial businessman to his former lover, who may or may not be the earth (“Oh Gaia, if that’s your name/Treat you like dirt, but I don’t want to blame…”)

That leads us to “Home Sweet Home,” which frustratingly sums up all the off characteristics of this second album. The songwriting feels a bit like Peter’s version of Randy Newman (last heard on “Waiting for the Big One”), the pedal steel seems like we’re in a country song, and we have another one of the indifferently recorded scratch vocals. And it’s about a man whose wife commits suicide, killing his child at the same time; despairing, he gambled with the insurance check and won big, buying a country home far away from his eleventh floor walk-up. The last verse features one of Peter’s most challenging-to-listen-to vocals, as his high vocal obbligato provides an impression of the man’s wordless sobs. It feels dark in an exploitive way. We will get much more earned dark passages in future albums, but here it feels like he’s trying on someone else’s pain.

Ultimately 1978’s Peter Gabriel is a frustratingly uneven album. There are some great songs—both “On the Air” and “D.I.Y.” are in the canon of his greatest songs, and “Exposure” is affecting, but many of the others suffer from the rapid approach to recording and writing. He took more time on the next record, and it showed. We’ll listen to that one next time.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

BONUS: Fripp connected a series of albums that he produced in the late 1970s, including Peter Gabriel, Daryl Hall’s Sacred Songs, and his own debut solo album Exposure, as a loose trilogy. He re-recorded “Exposure” for the latter album, and it’s … really something, thanks to vocals by Terre Roche of the Roches:

BONUS BONUS: The band for this tour, with Sid McGinnis in for Fripp, was a tight machine. Here’s a German performance of “On the Air” from 1978 that shows Peter had been watching punk acts: