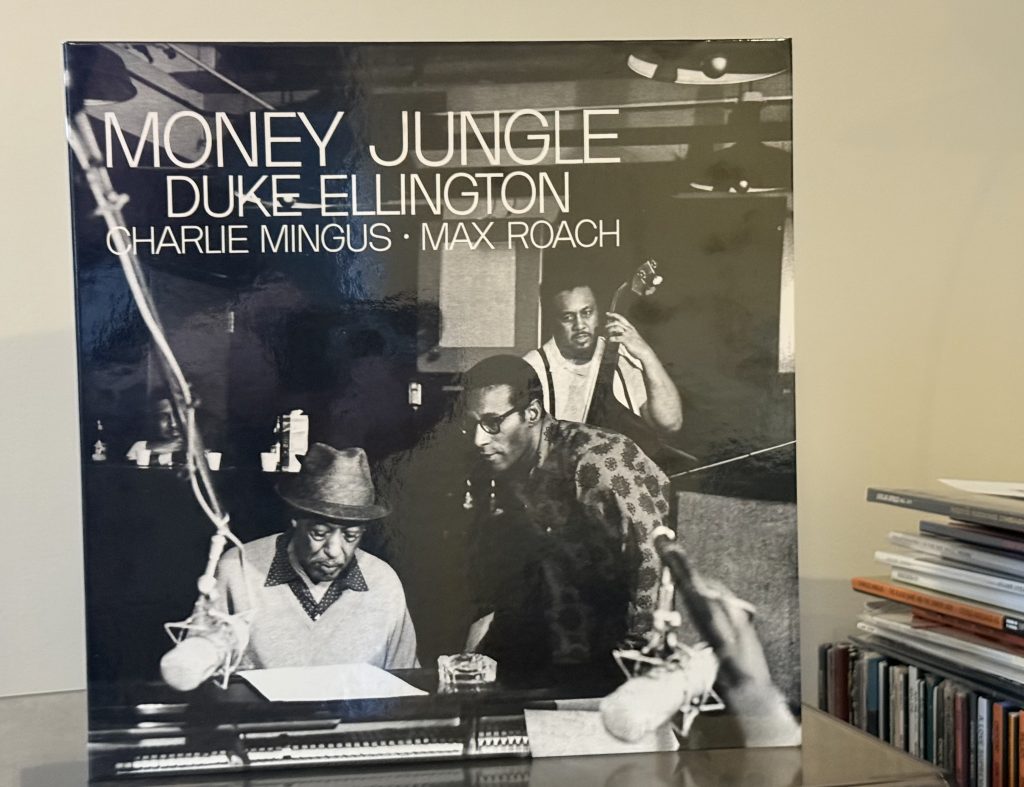

Album of the Week, January 17, 2026

If you listen to enough music, you’ll inevitably hear about those albums that almost never happened because of drama during the recording sessions. The bands who come up in this kind of conversation might be the Beatles, Metallica, or Fleetwood Mac; it’s less common to hear about jazz players coming to blows. And then, there’s Charles Mingus. Never an easygoing guy at the best of times, Mingus’ legendary temper almost ended what turned out to be one of his most legendary sessions prematurely.

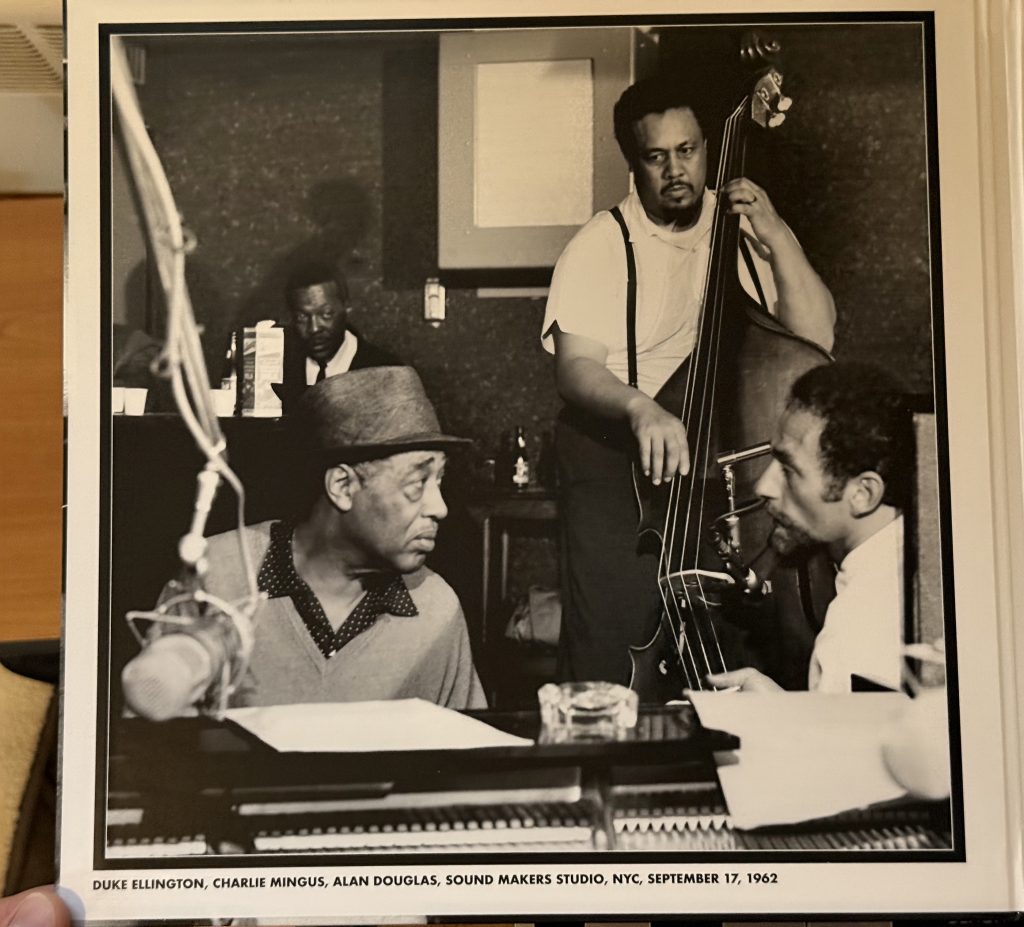

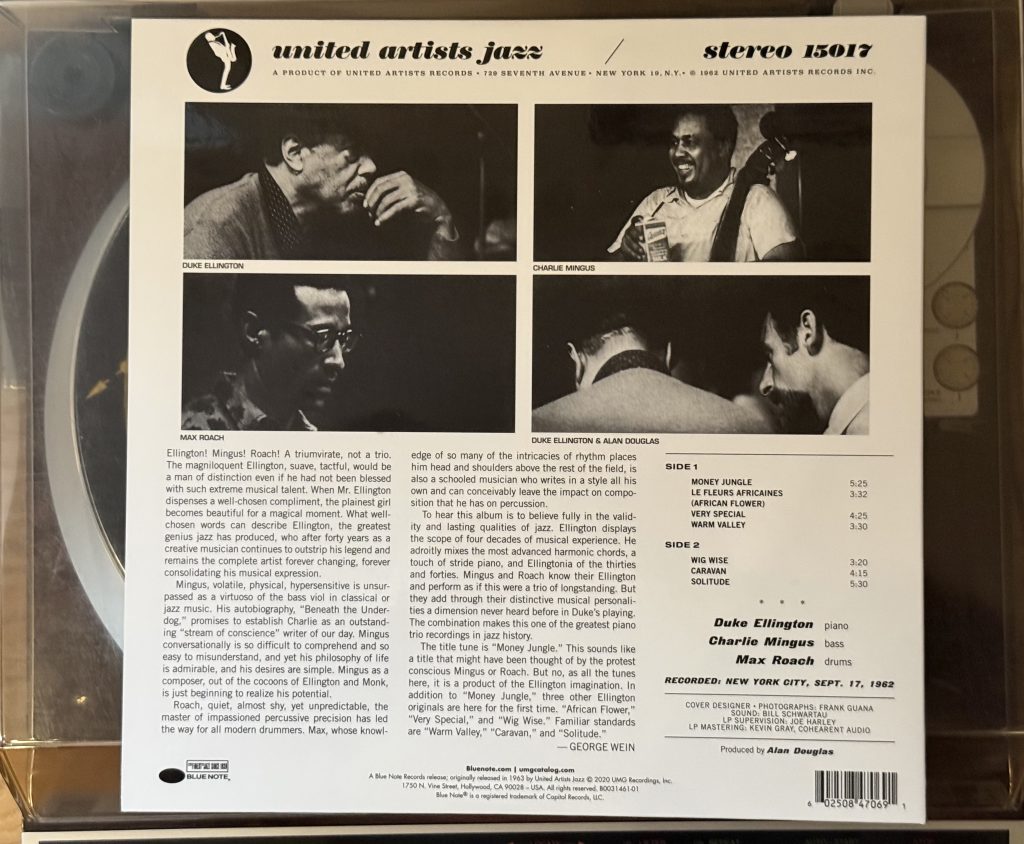

It started with the logistics of the session. In 1962 Duke Ellington came to producer Allen Douglas, who was then working at United Artists Records, to see about doing a piano trio session. Douglas was excited and suggested Charles Mingus, who had been in Ellington’s band, as the bassist; Ellington agreed, and Mingus suggested bringing in Max Roach, with whom he had worked in Charlie Parker’s band, as drummer. Ellington didn’t have a recording contract at the time, so they used Mingus’s contract. Ellington suggested to the men that they think about what tunes they might like to record, and said they needn’t be Ellington compositions.

On the day of the session, Ellington came in with a sheaf of scores, including four new tunes written for the occasion. History doesn’t record Mingus’s reaction, but one suspects he could feel the session slipping away from him and he was frustrated. As the session got more and more tense with each song, he reportedly argued, with Ellington, Roach, or both, eventually leaving the studio. Stories vary about whether Ellington caught up with him at the elevator or the street, but Mingus was eventually persuaded to return and finish the session.

To say you can hear the tension in “Money Jungle,” the opening track in the album’s running order as released,1 is an understatement. Mingus opens with four bars, opening with the low subdominant of the minor scale followed by two hard pizzicati an octave up. Hard is also an understatement; he bends the strings so hard that the pitch distorts. Ellington follows with explosive, dissonant chords as Roach plays a circular pattern on the drums. Eventually all the players lock in on a blues, but it’s not an easy journey. Mingus alternates more conventional walking parts, stuttering stabs, and high runs on the bass as Roach drops snare rolls, fills and other surprises in his part. At the end, Mingus abandons any pretense of conventional playing, hammering a series of suspended chords; the pianist waits him out eventually tolling a series of low notes to signal the end. If Mingus was attempting to assert dominance, Ellington appears to have showed that he could go toe-to-toe with him. (It’s thought that Mingus attempted to quit the session after this number.)

Which makes “Fleurette Africaine” all the more surprising. Like the opener, it was written for the album; unlike the opener, it’s a classic Ellington ballad. Mingus plays much more sympathetically here, but still adds new dimensions to the composition, playing shuddering arpeggi to which Roach reacts with polyrhythmic heartbeats and fills. Mingus plays alternate harmonies under the bridge, and the whole thing comes together just above a hush. It’s gorgeous.

“Very Special” is another twelve-bar blues, this one far less combative. Here Mingus’s bass improvisations are primarily in the space at the end of the twelve-bar repeat, or under Ellington’s third and fourth solo verses. That’s not to say he’s not innovating; some of the rhythmic patterns are quite striking, and the trio locks in on an improvised secondary rhythm during the bridge. But compared to the apocalyptic feel of “Money Jungle” it’s left in a supporting role on the album. It’s followed by “Warm Valley,” with the first verse played solo by the pianist. A classic Ellington composition, named after a landscape feature he saw from the train in Oregon that reminded him of a reclining woman, here it’s a duet with the bassist, with only subtle brush work by Roach adding atmosphere.

“Wig Wise” is the last of the newly written works for this session. A classic Ellington tune, it unfolds at first like a Bach improvisation, all pieces in place, but slowly Mingus starts to sound as though he’s slipping a gear, shifting the emphasis on the beat, leaving deliberate holes in the texture, moving the rhythm. He finds a second melody entirely in the bridge, and responds to the gap left by Ellington at the end of each verse with a different fill each time, finally ending the tune with a plucked glissando up to the highest note on his fingerboard.

“Caravan” was written by Juan Tizol, he of the fight that got Mingus kicked out of the Ellington band. It’s unclear whether it’s the association with Tizol or the fact that the number was recorded late in the session, with temperatures already high, but this one also feels like a raised-voice discussion between Ellington and Mingus. The bassist is imaginative in his fills, but there are places where he continues to run in his pattern rather than following the changes in the music, and at the end he and Ellington alternate attempts to close the track out. This is probably Roach’s high point on the album, with explosive statements from the drums and a variety of tonalities from his kit. (I included this track on an Exfiltration Radio show featuring noteworthy bass performances a few years ago.)

The set closes with “Solitude,” again with Ellington opening the tune solo. Whether to offset the explosive nature of the rest of the recording, or just as a reflection of the innate quietude of the track, it feels almost like an interior monologue at the beginning. Mingus supports the pianist with single notes in the second chorus, but as he modulates the tune into another melody the bassist falls silent, rejoining along with Roach as the composer reenters the melody, now forthright and triumphant. At the end, Mingus plays a rolling fanfare over Ellington’s final chords; Ellington puckishly refuses to resolve the harmonies so Mingus finally does it for him as the album draws to a close.

Whatever the tension in the room, Money Jungle is a complete artistic success, a portrait of music being made amid conflict and frustration. It’s also an opportunity to hear Mingus as a performer, apart from his compositions and his band, and to hear his rhythmic and harmonic imagination at play. Next week we’ll hear those qualities in the context of his compositions once more.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

BONUS: The great drummer Teri Lyne Carrington played the whole Money Jungle album live during the 2014 Internationale Jazzwoche (jazz week) in Burghausen, with a sextet that included Aaron Goldberg on piano, Tia Fuller on saxophone, flute and vocals, Antonio Hart on saxophone and flute, Claus Reichstaller on trumpet, and James Genus on bass. Here’s the title track:

BONUS BONUS: “Fleurette Africaine” has entered the repertoire, with recordings by Gary Burton, Horace Tapscott, Vijay Iyer, and many others. Here’s a 2017 version with Norah Jones on piano and vocals, Brian Blade on drums, and Chris Thomas on bass, from Ronnie Scott’s jazz club in London:

- A 1980s reissue sequenced the album by recording order and added alternate takes and bonus tracks; this version is what’s available on the CD. ↩︎