Album of the Week, January 24, 2026

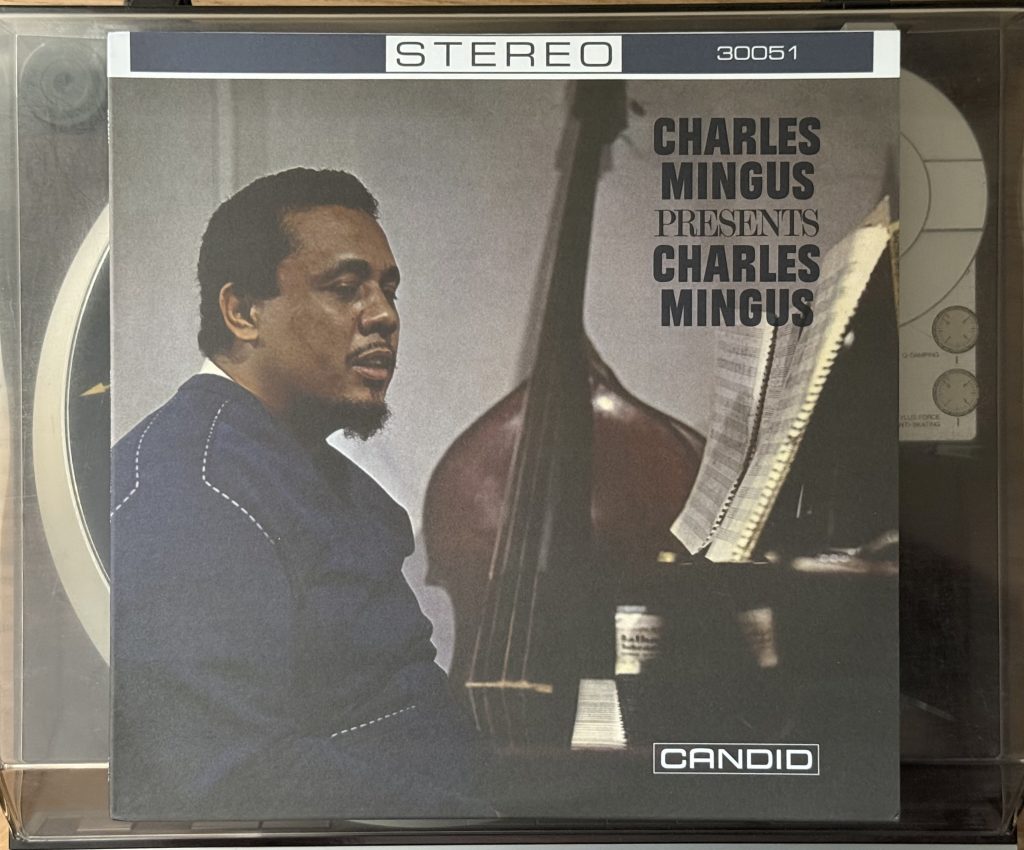

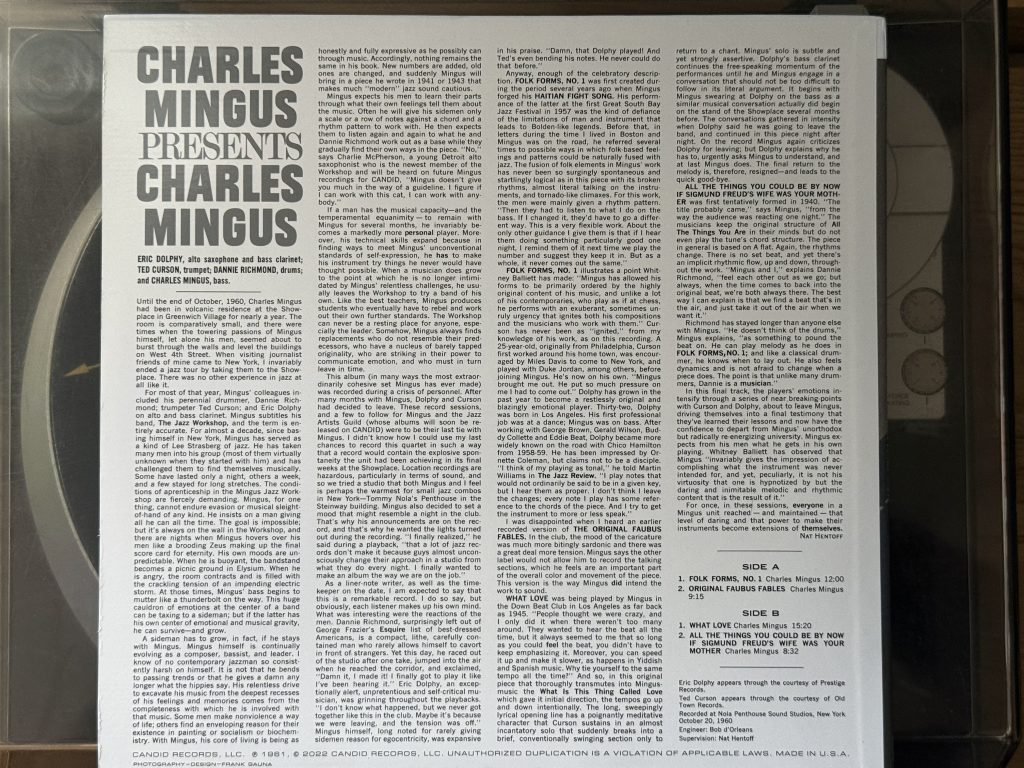

Given the challenges with labels that we’ve seen other jazz geniuses have (cf: Miles’s contractual obligations with Prestige, Trane’s back material being issued for years (again by Prestige), Monk’s contract being bounced around by Riverside until their bankruptcy), it’s remarkable to contemplate Charles Mingus’ seeming ability to record on any label he wanted. Managing to record on Atlantic and Candid simultaneously, doing a few releases on Columbia, bopping over to United Artists, it’s interesting to note that he wanted even more label time—and with Bob Thiele and Impulse!, he found it, at least for a while.

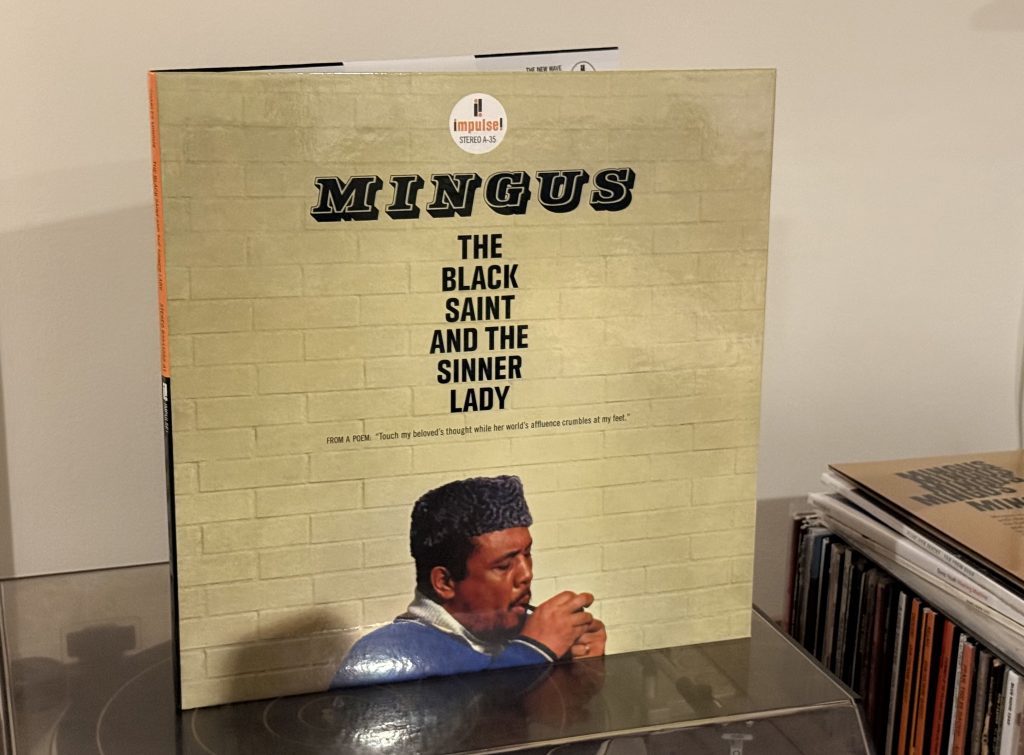

Thiele was a few years into his stewardship of the Impulse! label, and had recorded four major Coltrane albums—Coltrane “Live” at the Village Vanguard, Coltrane, Duke Ellington and John Coltrane, and Ballads—by the time that Mingus entered the studio. Mingus’s session, held January 20, 1963 at the familiar Atlantic studio in New York, was to be both in a line with these great records and totally different. While the session was, like the string of Coltrane Impulse! records, a career-defining work of genius, considered along with Mingus Ah Um to be the summation of his compositional powers, it was different in that it was composed for a much larger group, an eleven-piece jazz orchestra.

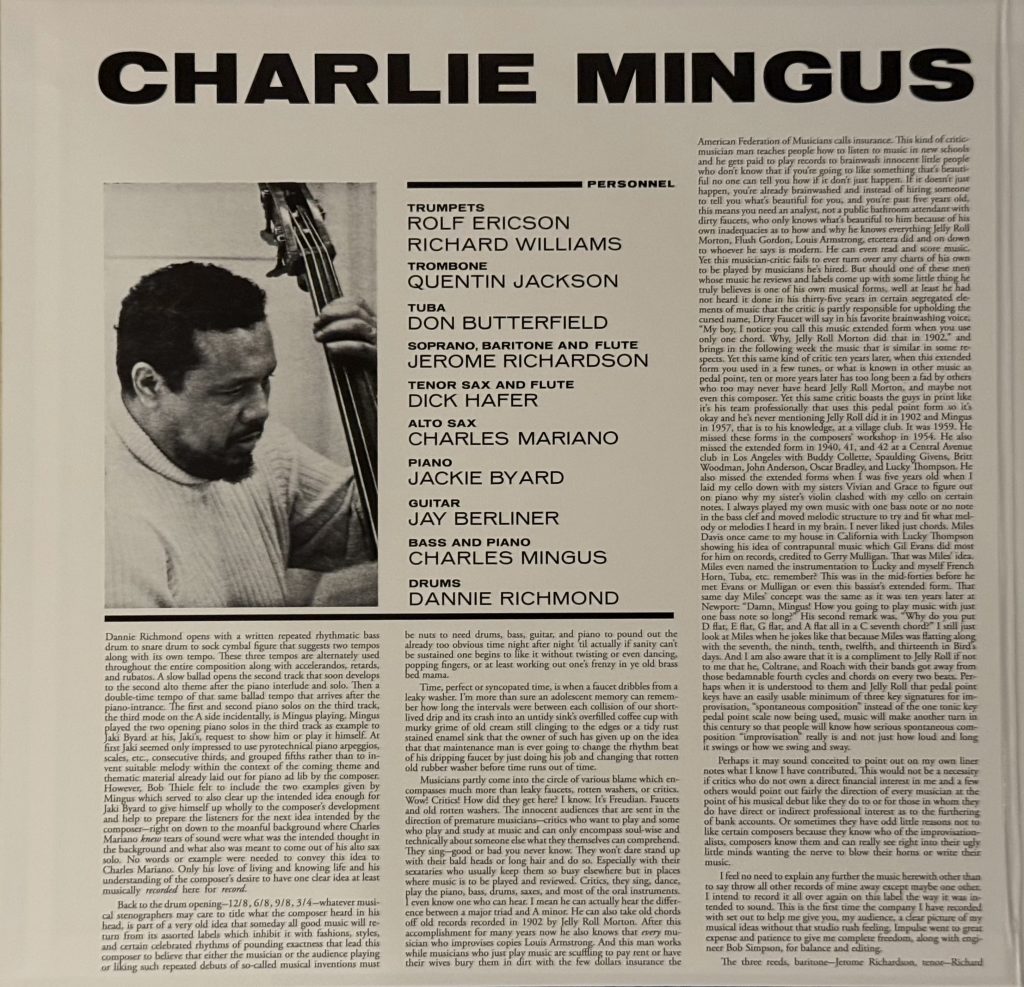

Effectively it was someone else’s orchestra. Bob Hammer, a pianist who had performed with Mingus on his totally bonkers A Modern Jazz Symposium of Music and Poetry and would later play with Johnny Hartman, had formed the orchestra only to have Mingus take it for a run at the Village Vanguard for six weeks, during which time he worked out much of the compositions of the album. In addition to Hammer’s arrangements, the group also featured the redoubtable Dannie Richmond on drums, Don Butterfield on tuba, Jerome Richardson on soprano and bari sax and flute, Charlie Mariano on alto sax, Dick Hafer on tenor sax, Rolf Ericson and Richard Williams on trumpet, Quentin Jackson on trombone, Jay Berliner on classical guitar, and Jaki Byard on piano. Byard, hailing from Worcester, Mass, had played professionally from age 16, was drafted into the Army at age 19 (where he mentored the Adderley brothers), then returned to Boston where he played with musicians including Sam Rivers and Mariano. Byard joined Mingus’ band with his legendary Town Hall concert in 1962 and played regularly through 1964, and off and on in the bassist’s bands through the end of his life.

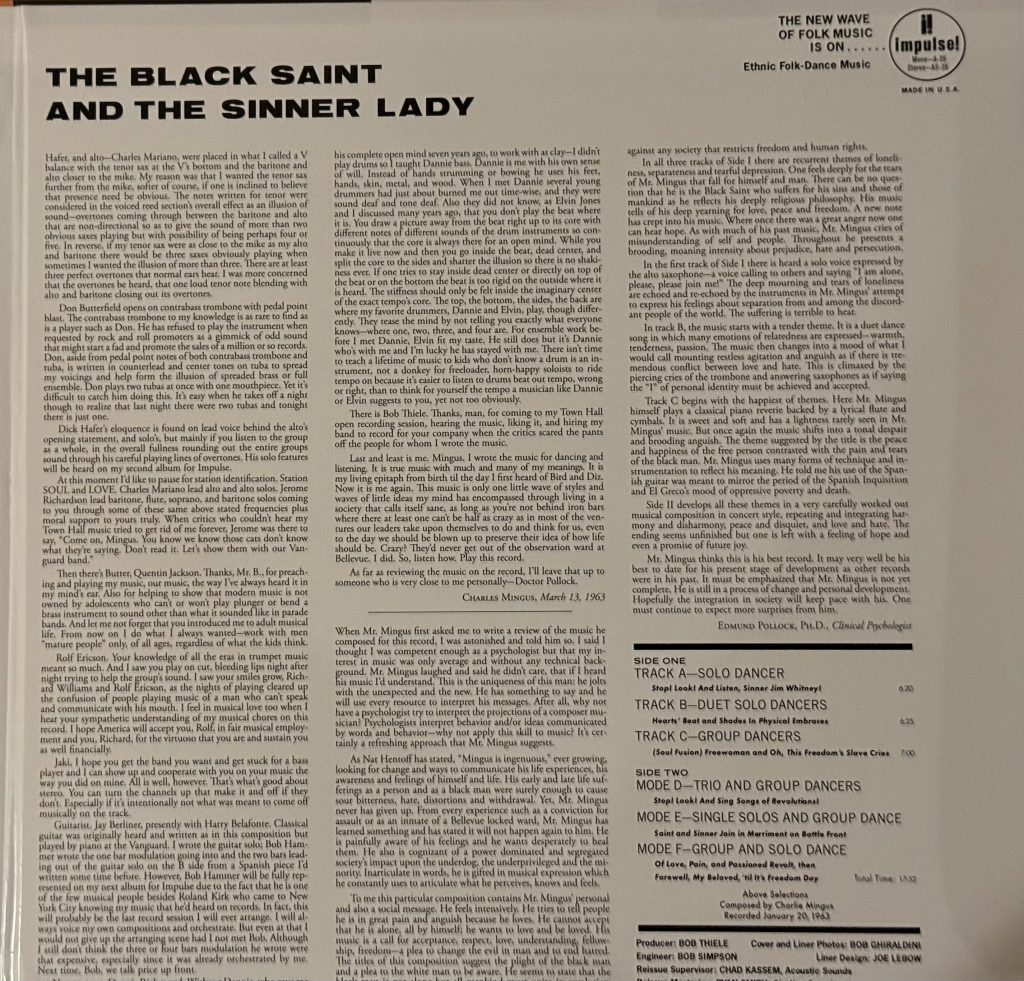

Mingus himself writes astonishingly complete (and verbose) liner notes describing the composition; I’m going to restrain myself to impressions.

“Solo Dancer” opens with a a flourish from Richmond and a solo voice on the alto sax (Mariano) crying in the wilderness against a pedal point of Jerome Richardson’s baritone, Don Butterfield’s tuba (both in the right channel) and collective improvisation by the group against a III – IV vamp—which is to say, a thick cluster of sound out of which solo voices pop. Richardson’s soprano sax solo against a cluster of trumpets grinds deep into that vamp, until the piano calls an end to the dance.

“Duet Solo Dancers” opens with that piano, finally taking us out of the repeated two-chord vamp into something like an Ellington ballad. The movement is subtitled “Hearts’ Beat and Shades in Physical Embraces,” and one imagines the dancers sharing a tender moment before suddenly a pulse in the tuba signals a shift in mood; an argument perhaps? The tempo ebbs and flows as though the fight is picking up volume, until a climax is reached; the fight music returns, this time in a note of regret, until the dancers reconcile and the ballad returns once more.

“Group Dancers,” subtitled “(Soul Fusion) Freewoman and, Oh, This Freedom’s Slave Cries,” opens with the piano (played by Mingus) introducing the third theme, a descending trill from the fifth down to the tonic and then up to the submediant. After some conversational interjections from the band, they pick up the new theme and try it out. The piano returns, playing a segment of Ravel-esque beauty complete with moments of parallel beauty, and then the band picks up the theme once more, with the trumpets, then the flute, then the other instruments picking up the descending theme. Ultimately a new theme (the “freedom’s slave cries?”) emerges, with layers of themes in a long vamp for the entire orchestra, as Mingus’s bass urges the ensemble forward, controlling the tempo as it surges forward and ebbs back. A closing note from the alto leaves us in a cliffhanger going into the second side of the record.

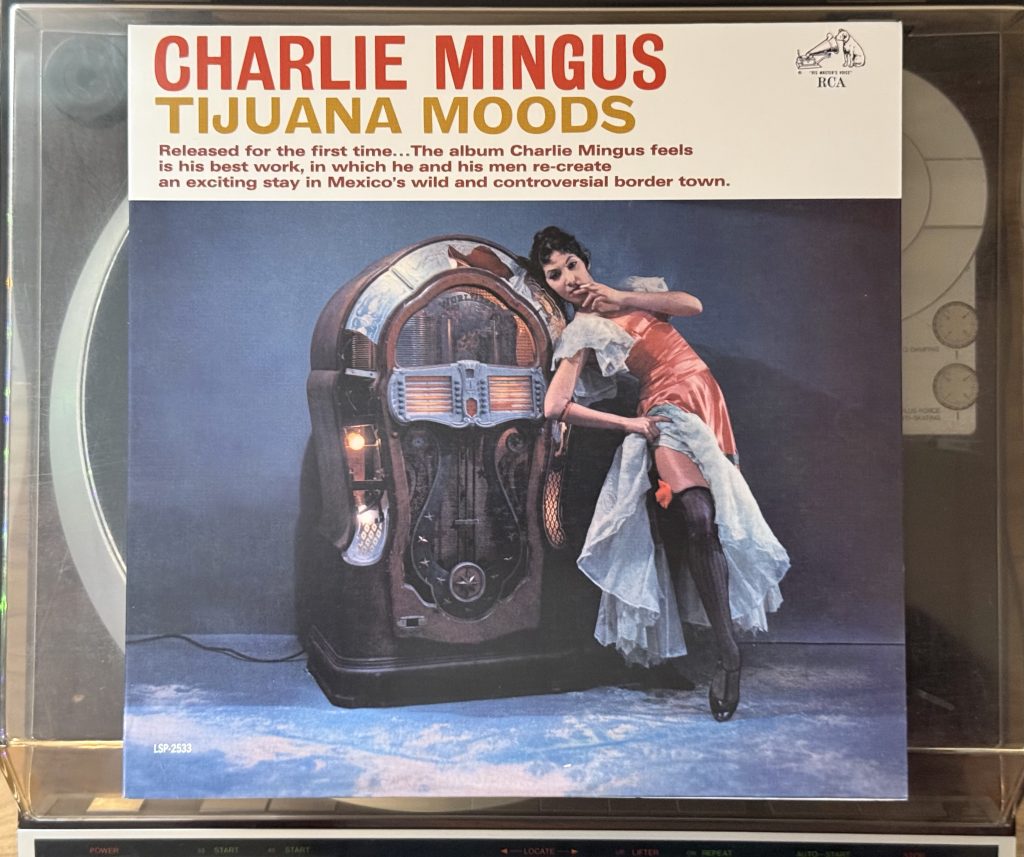

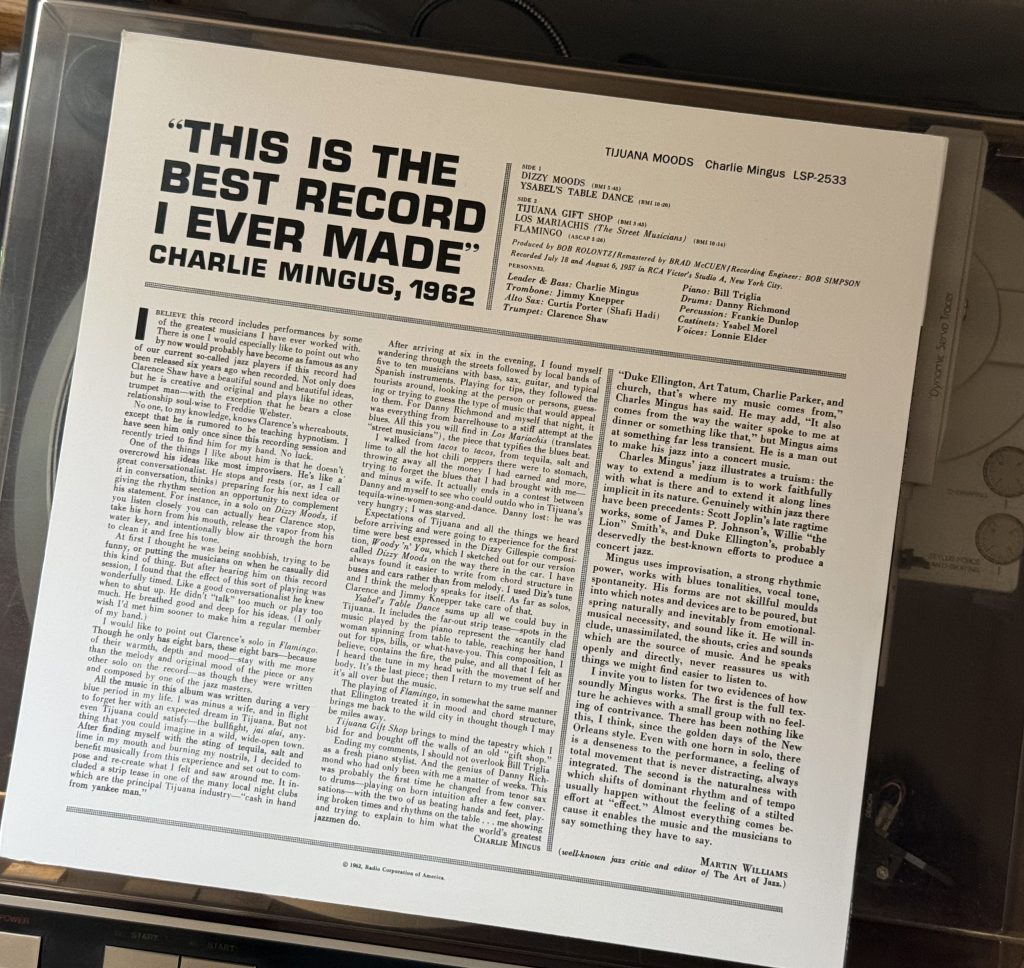

“Medley: Trio and Group Dancers/Single Solos and Group Dance/Group and Solo Dancers” is a single long track that comprises the second side. Opening with conversations between the instruments followed by a soliloquy from Mingus on the bass, the muted trumpets lead us into a sort of cockeyed ballad once more. The dense structure is broken apart by Jay Berliner’s Spanish guitar flourish; one imagines a dancer in full flamenco garb taking the center stage for a moment. The ensemble is not so easily brought into this new sound world, and a tumult follows as they improvise over a theme that slowly reveals its similarity to the “Los Mariachis” theme from Tijuana Moods. Another break from the piano (this time by Jaki Byard) introduces a recapitulation of the descending theme from “Group Dancers,” followed by a Liszt-like cadenza and the descending theme’s return.

A series of solos follows, with the alto sax leading into the group and solo dance “Of Love, Pain, and Passioned Revolt, Then Farewell, My Beloved, ’til It’s Freedom Day.” The love theme from the Duet Solo Dancers returns, introducing a new theme, built atop a major-key vamp, that slowly accelerates as the revolution gains momentum, until the whole ensemble reaches a sort of exhausted collapse, only to start all over again. Ultimately the band reaches a jubilant climax punctuated by the shouts of the different instruments, then returns to an echo of the opening music, as if to say “Look out, folks, we aren’t done yet.” A massive final saxophone solo points at an angle into the sky, as if to promise better days lie yet ahead.

Mingus came to Impulse! following the near-disaster of his Town Hall concert, at which he premiered what eventually became his long-form composition Epitaph in a “jazz workshop” model, with the players working out ideas on stage. In the liner notes, he thanks producer Bob Thiele (who had become the lead at Impulse! following Creed Taylor’s decampment for Verve) for “for coming to my Town Hall session, hearing the music, liking it, and hiring my band to record for your company when the critics scared the pans off the people for whom I wrote the music.” He found the experience congenial, noting, “This is the first time the company I have recorded with set out to help me give you, my audience, a dear picture of my musical ideas without that studio rush feeling, Impulse went to great expense and patience to give me complete freedom…” He also said “Throw all other records of mine away except maybe one other. I intend to record it all over again on this label the way it was intended to sound.” We’ll hear the result of that session next time.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

BONUS: There have been a few attempts to essay a live performance of Mingus’ great composition. This 2013 performance by the Nu Civilization Orchestra in London is worth a listen:

BONUS BONUS: The Nu Civilization Orchestra has kept the work in repertoire, and recently brought the work to the Barbican, along with dancers!