Album of the Week, February 14, 2026

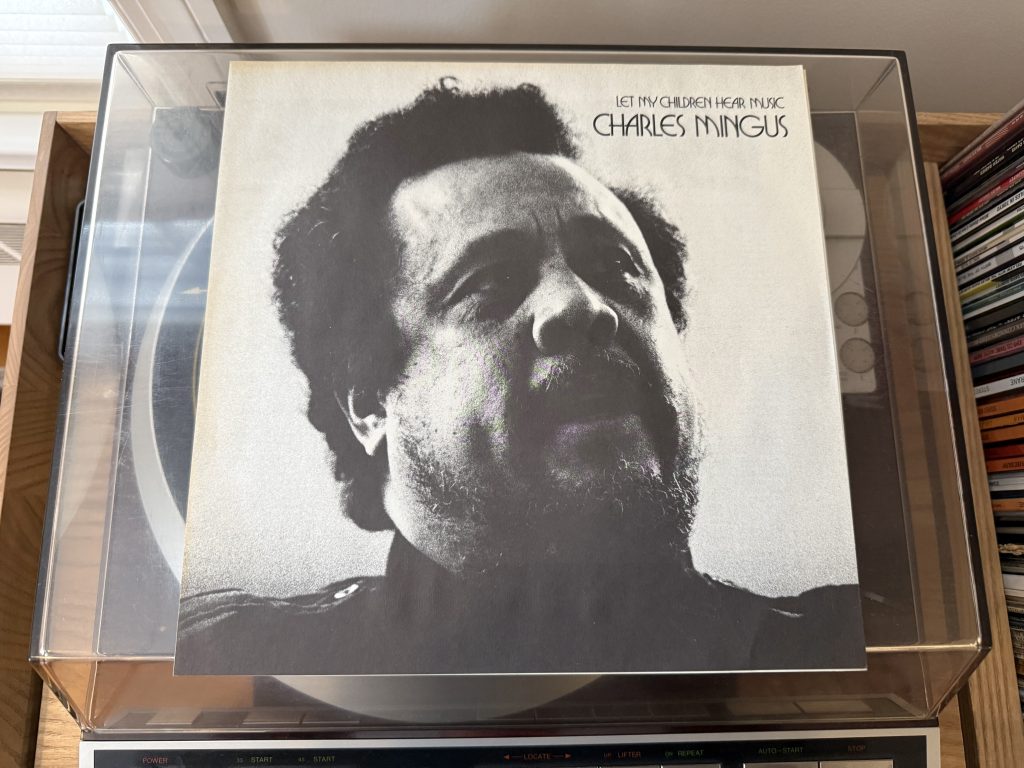

When we last checked in with composer and bassist Charles Mingus, he was on a career high that was about to enter a downturn. Following Mingus at Monterey, he toured heavily but was without a recording contract, and was evicted from his apartment for nonpayment of rent in 1966. But Mingus seems to have always had the ability to convince the labels to place a bet on him, and the fall of 1971 found him working again with Columbia’s Teo Macero on a big-band recording of all-new compositions.

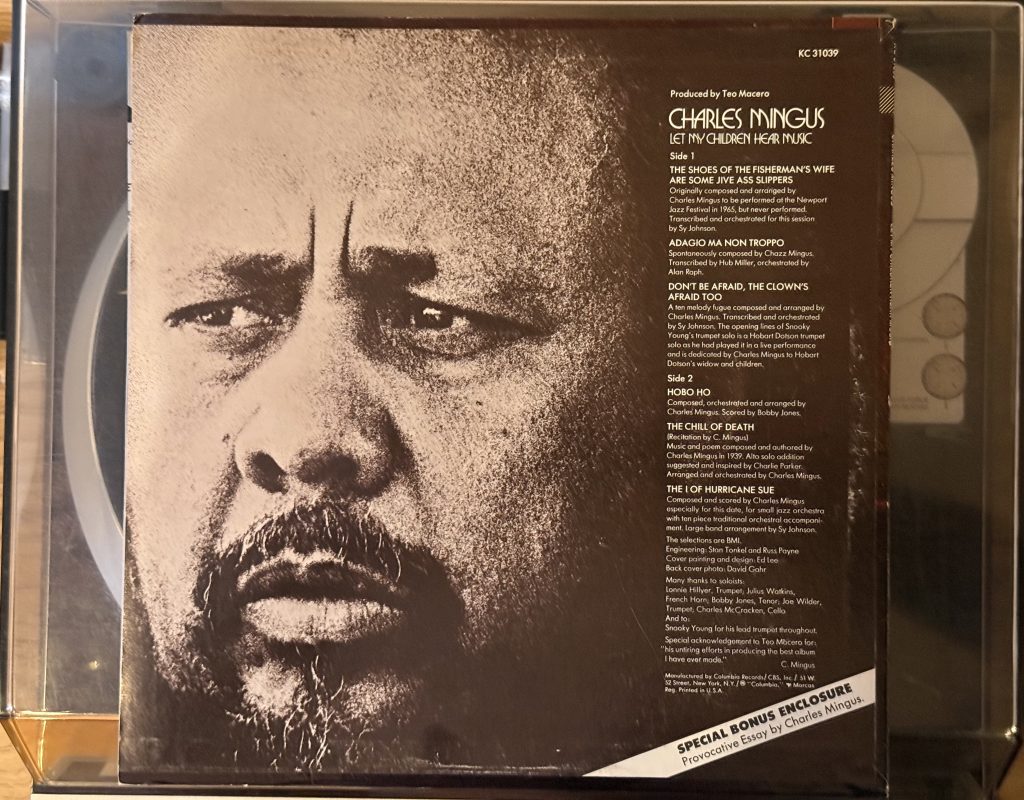

And what a band! Across six recording sessions between September 23 and November 18, a small army of musicians worked on the recording that became Let My Children Hear Music, including Lonnie Hillyer, Jimmy Nottingham, Joe Wilder, and Snooky Young on trumpet, Jimmy Knepper on trombone, Julius Watkins on French horn, Charles McPherson on alto sax, Jerry Dodgion, Bobby Jones, Hal McKusick and James Moody on reeds; Charles McCracken on cello; Jaki Byard, John Foster, and Roland Hanna on piano; and Dannie Richmond on drums. Teo not only produced but also conducted the orchestra and played some alto sax. And alongside Mingus’s bass were three additional bass masters—no less than Ron Carter, Richard Davis, and Milt Hinton. And those are only the musicians we know about—some remain uncredited on the recording due to contractual issues. Collectively they gave Mingus’s music a sound that he had never gotten on record before, with a combination of power and polish.

“The Shoes of the Fisherman’s Wife Are Some Jive-Ass Slippers” might be my favorite Mingus title of all time, even considering that this is the man who wrote “All the Things You Could Be By Now If Sigmund Freud’s Wife Was Your Mother.” From the very beginning of the track we get two impressions: this music is ambitious, and this band is tight. The horns and reeds play the opening melody slowly against a chromatic scale in the bass and low instruments; there’s a coda of sorts to this part signaled by an “Also Sprach Zarathustra” timpani roll, a series of chord changes, and then we’re into a brisk waltz that pauses, then shifts into 6/8 time. The horns and reeds introduce a descending motif that keeps interrupting the waltz until the piano signals another transition and a recapitulation of the top melody. This time the band picks up a new version of the slow theme in a fast 4/4 time, that builds in intensity up the chromatic scale until there’s a sudden swoon and lapse back into waltz time. We’re left to wonder how many of the sudden shifts were scored and how many were the product of Teo Macero’s genius editing skills. All throughout the chord progressions and gestures are wild and free (that timpani glissando against the descending motif at the end!) and the band swings as hard as anything Ellington ever did.

“Adagio, Ma Non Troppo” begins with a lone reed followed by a lone flute, playing music that seems birthed from “Sketches of Spain.” There are interludes of piano and guitar, rafts of flutes and clarinets, and a fast dance with three arco basses all soloing at the same time. True to the title, some moments are downright symphonic here; this section is probably the least swinging on the record, but those bowed bass solos keep us grounded at the same time that they reach for the stars. When the saxophones take the theme it feels like a moment from a Keith Jarrett European quartet composition.1 The whole thing is breathtaking in both composition and performance.

“Don’t Be Afraid, The Clown’s Afraid Too” starts in the circus, with recorded lion roars and elephantine trumpet blasts, before the band swings into a circus theme underscored by oompa bass and tuba and a brilliant walking bass line. The simultaneous solos between tenor sax (right channel) and alto sax (left) stretch the brain to hear all the passing harmonies as the players cross over and solo past each other. Another circus interlude and a brisk Mingus pizzicato solo sets up a chorus of twittering bird flutes, and the rest of the track tosses the theme from section to section before returning to the oompa theme once more before returning to the circus again to take us out of Side A.

“Hobo Ho” opens with a gutsy, funky bass line that anchors us firmly in the tonic. The tenor sax sets up the first melody with almost subsonic support in the lowest instruments. There are horn bursts that wouldn’t have been out of place on The Cat. This is music for a rumble, standing alongside “II B.S.”/“Haitian Fight Song” as some of Mingus’s most groove-driven work.

“The Chill of Death” begins with a Mahlerian moment, a tremolo from the basses over a timpani hit and the orchestra. Mingus recites a poem that dates from the beginning of his career; written in 1939, it captures the constant tension in his work between wild life and the fear of being forgotten in death. After the recitation there’s a sustained organ tone and a free alto sax solo by Charles McPherson over a shifting, uneven instrumental background—sometimes marching to the graveyard, sometimes joyfully dancing, sometimes anxiously peering around the corner. The piece ends with a rare audible splice as McPherson plays into a descending glissando and crescendo by the rest of the band; I wonder how much improvisation was left on the cutting room floor by Macero.

“The I of Hurricane Sue” ends where we began, the second piece recorded in the very first session. There are wind effects and corrugaphones beneath a free intro before the band snaps into a tightly wound, swinging melody. The work ends with dueling pianos, Jaki Byard vs. Roland Hanna, as the whirly tube and winds blow us away. This characteristic of alternating chaos and gorgeously played symphonic jazz is what ultimately sets Let My Children Hear Music apart as a work of staggering genius and an apex of Mingus’s compositional career.

The brilliance and tragedy of Mingus’s life wasn’t yet done. He had a few epochal albums for Atlantic Records, Changes One and Two, ahead of him, but he also had a deeper challenge—ALS, which began to rob him of his mobility and his ability to perform. As a composer and bandleader, he still had some milestone records ahead and we’ll hear one last one next week.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

BONUS: There is an honest-to-goodness bonus track, in the original CD reissue sense, on Let My Children Hear Music. Recorded on the second recording date (September 30) following “Hobo Ho,” “Taurus in the Arena of Life” was first issued in 1992 on the first CD release of the album. It’s a nifty hybrid between a classical sonata in the piano and a blues in the horns, who take a trip to Mexico where things get marvelously strange.

BONUS BONUS: There are a few attempts to play this music live out there, but not many—which is why it came as a shock to find this sextet performance from a jazz ensemble in the University of Virginia’s Old Cabell Hall Auditorium, of all places! I don’t think that’s any of the main faculty up there, but I can’t see the bassist so it just might be Pete Spaar.

- Don’t worry, you didn’t miss a week. We’re not to Keith yet, but we’ll get there eventually. ↩︎