Album of the Week, February 7, 2026

Last week we witnessed Charles Mingus solidifying his place in the pantheon with an album that realized some of his greatest compositions with definitive performances (and contractually required placeholder titles). As we noted, Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus marked the reunion of the great bassist and his avant-garde compatriot Eric Dolphy. Mingus took the band on tour to Europe; Dolphy stayed there and died in a diabetic coma.

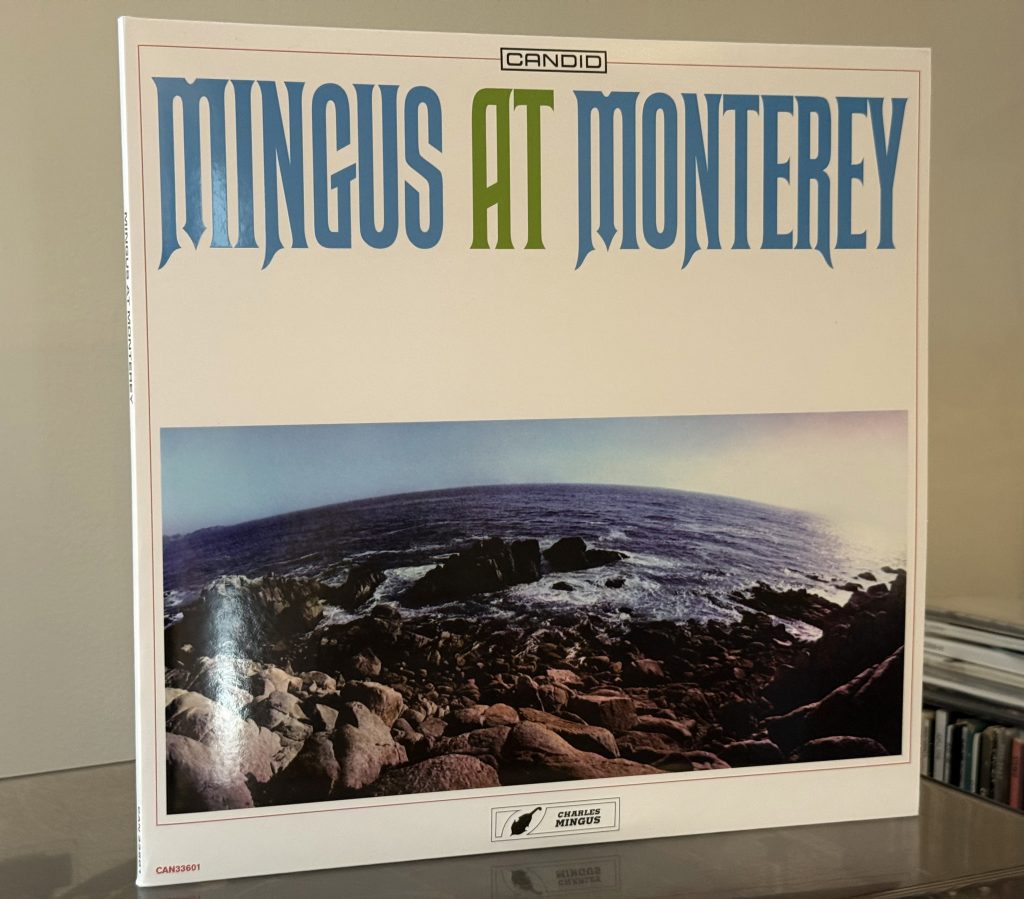

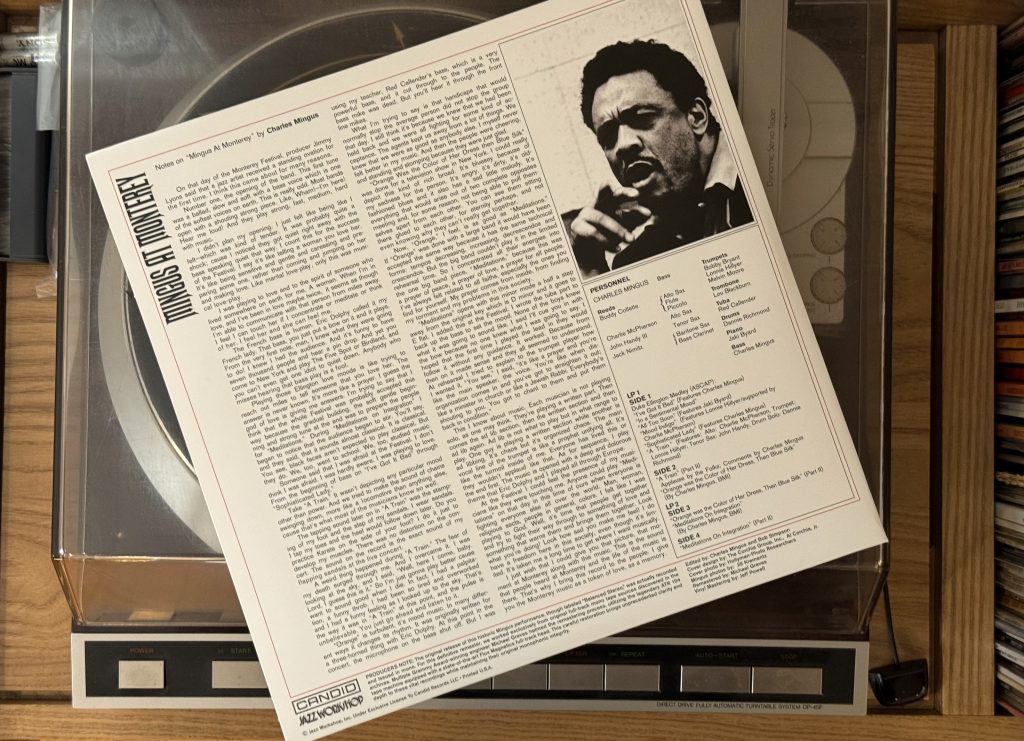

Given these facts, one could forgive Mingus for falling back to the familiar and focusing on that “greatest hits” repertoire, or from pulling back from touring and performing. Fortunately for us, the way Mingus dealt with challenges was to work and to create. His performance at the Monterey Jazz Festival on September 20, 1964 captured him doing both, with a band that had a rhythm section of Mingus stalwarts (Jaki Byard, Dannie Richmond) and a horn line consisting of Lonnie Hillyer on trumpet, Charles McPherson on alto and John Handy on tenor; Handy, an old Mingus band hand, rejoined at the last minute after Booker Ervin was hospitalized. For the last number, the band expanded into a big band formation, with Bobby Bryant and Melvin Moore on trumpet, Lou Blackburn on tuba, Red Callender on trombone, Buddy Collette on flute, piccolo and alto, and Jack Nimitz on bass clarinet and baritone sax. The performance gives us something old and borrowed, something new, and something blue (and orange).

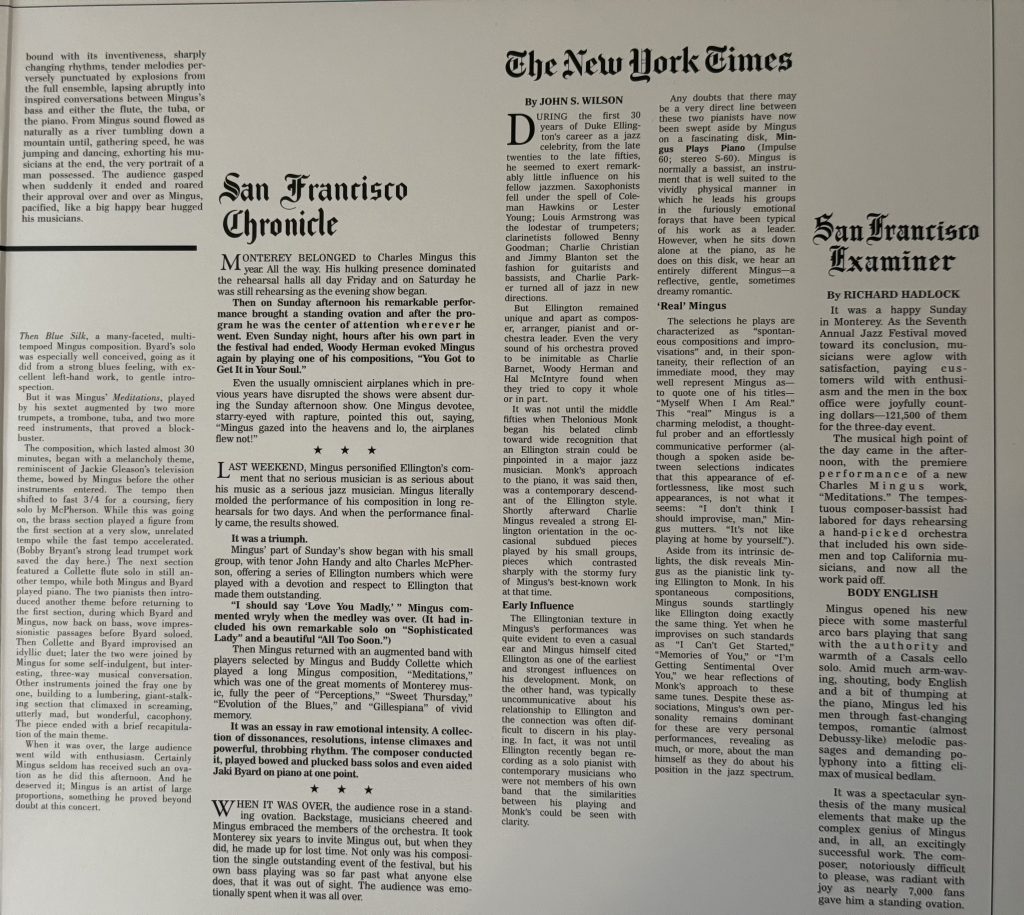

The “Ellington Medley: I’ve Got It Bad — In a Sentimental Mood – All Too Soon — Mood Indigo — Sophisticated Lady —A Train” is our “old and borrowed” segment, continuing Mingus’s exploration of the compositions of his inspiration, one-time boss and sometime sparring partner Duke Ellington. The band is relaxed; there’s a little stage chatter before Mingus takes a solo intro to “I’ve Got It Bad” with sparse accompaniment from Jaki Byard, and sensitive solos from McPherson and Byard. One Ellington classic flows into the next, all commented on from Mingus’s bass.1 Until, with a sudden break, we are taking the A Train. The band is jubilant to the point of almost unhinging, particularly Lonnie Hillyer’s imaginative trumpet and Handy’s tenor (the only shortcoming in the live recordings: the tenor saxophone is somehow overpowered by Byard’s piano). At the end there’s an unaccustomed solo from Richmond, showing that not only was he frequently the glue that held the adventuresome band’s performances together, but he could also blast a mean drum solo. The end dissolves into almost-dissonance, the band gasping over the final diminished chord. To the enthusiastic applause of the crowd, Mingus notes, “I imagine I should say ‘I love you madly’ at this point… Because, ah, if there is a recording, all the money will go to Duke Ellington, which is about due him; I’ve stole enough.”

Mingus announces “Orange Was the Color Of Her Dress, Then Blue Silk”; it’s a blues introduced with a shivering run in the bass over a stride influenced piano line. The trumpet and alto state the tune (Handy, from Mingus’ announcement, sat this one out because he had only had one day to learn the material!). Then suddenly we’re leaving the blues behind, falling into a woozy delirium that improvises on the chords and promptly lands us right back into the blues. McPherson’s solo continues to explore the tune in free time, but always coming back to the blues at the end, stretching the twelve-bar form to untold lengths. Byard’s statement anchors firmly in stride and the gospel blues, with the band smearing glissandi and shouting behind him, until everyone drops out and he plays something closer to a sonata. The kaleidoscope shifts again; Hillyer is here with something halfway between New Orleans and the Village Vanguard, then the band returns to that stretched out blues once more, leaning into it until the penultimate bar stretches out the seconds, finally turning into an unresolved sigh. (On the two record set, the composition splits between the back half of Side B and into the first half of Side C.)

Mingus announces “We’ll be back with more musicians,” and with the full band on stage launches into the arco solo that opens the premiere of “Meditations on Integration.” Out of a brief tune-up moment comes Mingus’ opening arco solo, sounding like a combination of the Beethoven 9 basses and the hora. The band enters with a busy line that Buddy Collette’s flute flies and darts above; McPherson’s alto answers with an anguished cry above the ongoing Stravinskyan rhythm of Mingus, Richmond and Byard and the stabs of horns from the rest of the band. Things threaten to dissolve into formlessness as Byard thunders on the low tonic and the band plays the chords of the melody in sequence, almost as choral interjections. McPherson returns to the melody as the band recapitulates the opening, rising to a chaotic crescendo out of which a duet of flute and low piano emerges. The band continues in this vein for some time, with Collette’s flute signaling turns in the melody and changes in the solo.

At almost 14 minutes into the tune there is a breathtakingly high bowed bass solo that sounds for all the world like a cello has appeared on the stage. Mingus plays a low stretto on the tonic and diminished supertonic as Byard speaks once more with moments of Liszt and Bud Powell; the duet between the two is an elegy from which Collette’s flute emerges once more, Ravel-like. A tremolo from Byard and rapt applause from the audience seem to signal another shift, but the interplay between Byard, Mingus and Collette continue until Mingus’s high shout calls Hillyer forward. The liner notes report a rehearsal conversation between Mingus and Hillyer, in which the composer tells him, “It’s like a prayer and you’re like the main speaker… Everybody’s shouting to you. You got to chant to them and put them back in condition.” And so the final portion goes, with the whole band hollering and Hillyer’s voice conjuring order forward. When the final chord comes, the audience gives Mingus a thundering standing ovation, the first in the entire history of the festival.

1964 was a career peak for Mingus; unfortunately, tough times were ahead. In 1966 he was evicted from his New York home; the only recordings to appear for the rest of the decade were older session recordings (Tonight At Noon, from 1957 and 1961 sessions for Atlantic records, is a classic) and live recordings from tour dates in Europe and America. That long drought would end in the early 1970s with a recording we’ll listen to next time.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

BONUS: Mingus’s tour of Europe with Eric Dolphy yielded early performances of “Meditations on Integration” and “Orange Was The Color of Her Dress, Then Blue Silk,” including this audio recording from the Salle Wagram in Paris on April 17, 1964:

- I believe one of the inspirations for Mingus’s bass technique is the contrabass recitative at the beginning of the fourth movement of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. Like Beethoven’s basses, he was always observing the performance and the melody closely, and always, always opining. ↩︎