Album of the Week, July 13, 2024

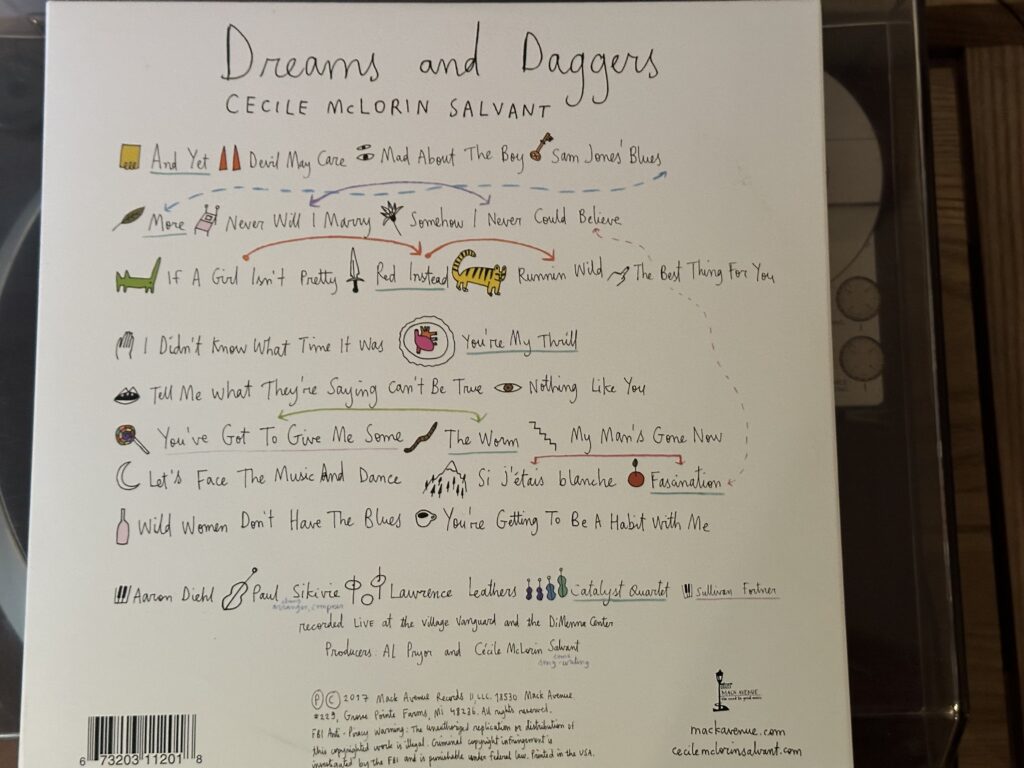

Cécile McLorin Salvant was on a roll. She had just picked up her second Grammy award for best jazz vocal album for Dreams and Daggers. No less a luminary than Wynton Marsalis had tapped her to tour with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, saying, “You get a singer like this once in a generation or two.” You’d be forgiven for thinking that she would rest on her laurels, or at least continue in the same path that had brought her to this point of success.

But being Cécile McLorin Salvant, this must have looked like a good time to start to make some changes. She began booking and playing dates without her longtime trio (Aaron Diehl on piano, Lawrence Leathers on drums, Paul Sikivie on bass)—instead, she and Sullivan Fortner appeared as a duo.

Fortner’s arrangements, orchestral in imagination and execution, meant that her musical horizons were not constrained; on the contrary, her new sound was freer and more wide ranging, borrowing from cabaret and stage even as she reached beyond the Great American Songbook for material. So Stevie Wonder’s “Visions” becomes something like lieder, her vocals alternately fierce and tender as Fortner’s piano sounds echoes of Brahms and Schubert, while “One Step Ahead” resonates with the sound of the R&B club with Fortner’s Hammond B3 organ, swinging against the merry waltz of the piano. We get a scampering, ominous undercurrent in Howard Dietz and Arthur Schwartz’s “By Myself” that turns into a solo that sounds like both parts of Bill Evans improvising in overdubs on Conversations With Myself. And Richard Rodgers’ 1962 song “The Sweetest Sounds” (from No Strings) has healthy dollops of boogie-woogie and Brahms forming a substantial solo number, introduced by Salvant’s wistful introductory reading of the tune.

This isn’t to say that the album is all Fortner, all the time. Indeed, Buddy Johnson’s “Ever Since the One I Love’s Been Gone” provides a vehicle for Cécile’s voice to spin a dark tale of sorrow and regret with subdued accompaniment in a live performance from the Village Vanguard, while the original “À Clef” hypnotizes with Salvant’s chanson performance, balanced with a touch of Nadia Boulanger in the accompaniment. Dori Caymmi’s “Obsession” is a breathtaking miniature of desire. And Dorothy Wayne and Ray Rusch’s “Wild Is Love” balances a nonchalant vocal delivery against the sound of an accompaniment that seems at imminent risk of tumbling down the stairs.

The jaunty organ of “J’Ai L’Cafard,” a 1930 French song by Louis Daspax and Jean Eugene Charles Eblinger, belies the darkness in Salvant’s performance of the desperate tale of a drug addict, a darkness that appears only in the final snarl of the chorus. For my ear, Salvant’s live reading of “Somewhere” could use a little of that snarl; for my taste, there’s a little too much portamento and rubato in her reading. But there are pleasures aplenty in Sullivan’s accompaniment, which finds an Ornette Coleman-like intensity in the long solo, and in Salvant’s hushed, unaccompanied final verse.

“The Gentleman is a Dope” finds Cécile back in delightfully familiar territory, with a swinging accompaniment underscoring a scornfully joyous narration over the Rodgers and Hammerstein original; the tune could easily have fit on any of her earlier albums, save for the thunderously cockeyed sonata of a solo between the first verse and the reprise. Alec Wilder’s “Trouble is a Man” is in more mature territory, a straight-up ballad sung with defiance and heartbreak in approximately equal measures. Cole Porter’s “Were Thine That Special Face” falls somewhere in between, as Salvant’s Petruchio attempts but fails to woo his Kate. “I’ve Got Your Number” starts as a cool rebuff that breaks down Cy Coleman and Carolyn Leigh’s cocky narrator before proposing that the two join forces; it’s enhanced by Fortner’s solo, which sounds a bit like Thelonious Monk sideswiping Bill Evans on a bicycle before riding off into the wobbling night.

“Tell Me Why,” the old Four Aces song, is given a tender balladic performance here, with Salvant’s reading of the line “Suddenly I’m feeling happy, so happy I want to cry, oh tell me why” shifting from joy to lump in the throat within the same phrase. Salvant returns to Rodgers and Hart for “Everything I’ve Got Belongs to You,” digging into lines like “I’ve got a powerful anesthesia in my fist/and the perfect wrist to give your neck a twist” with relish.

The album finishes with an ambitious live reading of “The Peacocks” that is both helped and hurt by Melissa Andana’s presence on saxophone; both she and Cécile want to take a fair amount of portamento on the chorus and they aren’t quite in sync, resulting in some clashes. But Andana’s saxophone solo is simpatico and gorgeous, and thematically the song, presenting the clash between the beautiful surface and the unknowable inner life of the loved one, is a good summation of the album. With it Salvant rounds out her survey of different modes of failure and joy from romantic love, presenting a more cohesive and wilder artistic statement than on her previous outings.

This was Cécile McLorin Salvant’s last album for Mack Avenue. As she won a Grammy for each of her preceding albums as well as this one, you could be forgiven for thinking that the world was running out of superlatives to give her. And you’d be wrong, but she shifted to a new label before we would learn about it. We’ll hear about that journey soon. Next time, we’ll talk a bit about another jazz vocalist who was shaking up his career, and his band.

You can buy or stream this week’s album on Bandcamp or listen to it on YouTube: