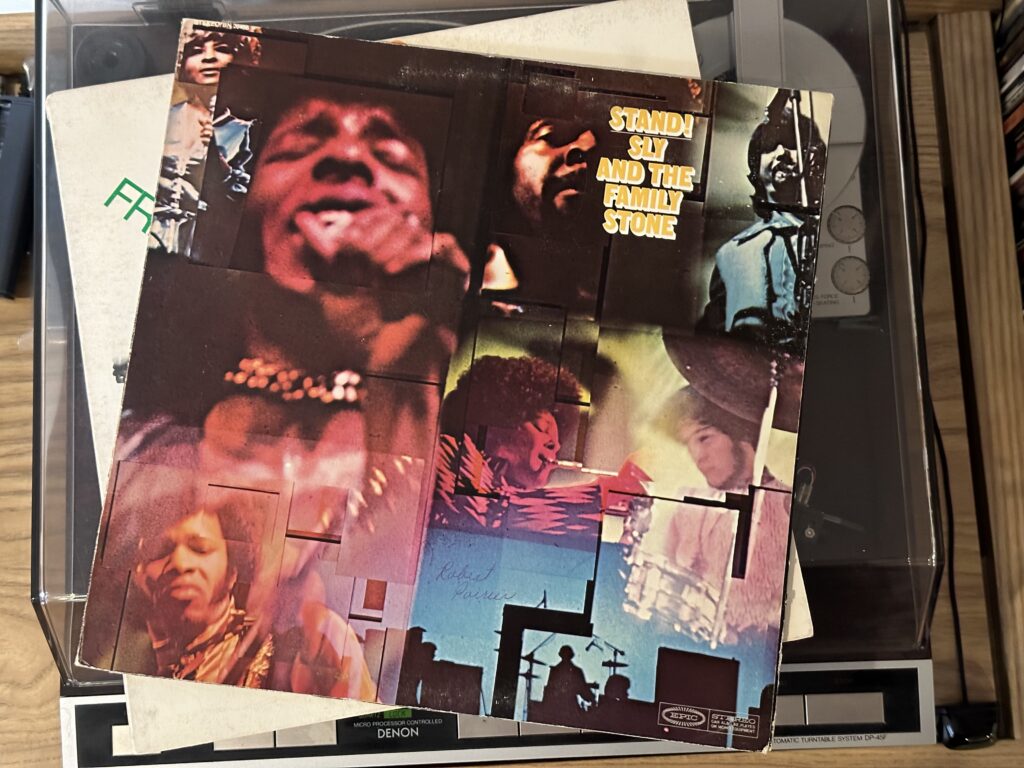

Album of the Week, September 16, 2023

After spending the better part of six months exploring the intersection of jazz and funk music through the catalog of CTI Records, I thought it might be fun to dig into the other side of the equation and talk about funk for a bit. This is going to be a brief, non-encyclopedic peek, because I don’t have some of the records that should really be at the foundation of this discussion. No James Brown, no Funkadelic… But I do have a few that I’ve wanted to write about for a while, so let’s dig in.

Sylvester Stewart was born in Texas in 1943, but his family moved to California when he was young, and you can hear it in his music—a sense of sunny optimism that shines through many of the tracks on Stand!. After singing in doo-wop groups and spending time as a DJ, he formed the band Sly and the Family Stone with his brother Freddie and his sister Rose, both of whom took the Stone stage name as their surnames. The band featured an integrated line-up, following the example of Sly’s high-school doo-wop group; an exciting line-up of vocalists; a great horn section; and the combination of Stone’s rock-influenced guitar and Larry Graham’s relentlessly funky bass.

All the group’s features are in full display on the album’s title track. “Stand!” starts out as a pretty straightforward rock song… for about four bars, until it changes keys in the second half of the verse. A chugging guitar and bass combo leads to the ecstatic chorus. The second verse follows the pattern of the first, and the second chorus starts the same way—and then an abrupt cut into funkytown plays out the last minute of the track, with an incredible syncopated bass pattern on the base and fifth from Larry Graham. Apparently Sly tested the song in a San Francisco club, got a lukewarm response, and went back and recorded the ending with a group of studio musicians.

The second track swerves hard into psychedelia. “Don’t Call Me N—, Whitey” has one of the great (if unprintable) titles of 1960s rock, and the verse (sung by Rose Stone) suggests irreconcilable racial tension and a weariness after the difficult 1960s:

Well, I went down across the country

“Don’t Call Me N—, Whitey”

And I heard two voices ring

They were talkin’ funky to each other

And neither other could change a thing

The rest of the track is pure psychedelic funk, with distorted vocals reminiscent of a harmonica solo over a fiery guitar solo. It wouldn’t be out of place on an early Funkadelic album.

“I Want to Take You Higher” is one of the great bits of synthesis on the album, as the pessimistic blues funk of the second track meets the relentless singalong optimism of the first. A gutbucket harmonica line alternates between solo and backing as each of the band’s five vocalists takes turns on the verse, with stacked harmonies on the chorus. But the most amazing feature on the song has to be the locked in rhythm section, with Graham, drummer Larry Errico, a chugging rhythm guitar, and handclaps hold the line ominously and doggedly on the tonic. The narrator may want to take you higher, but something is decidedly anchoring him to something a lot lower.

“Somebody’s Watching You” again starts out sounding like a pop song, with the verse’s alternating vocals from Sly and the Little Sister backing group over a great trumpet line from Cynthia Robinson. But Sly’s funky organ and the gospel inflected chorus bring the track out of the polite airwaves and into a much funkier place.

“Sing a Simple Song” is a straight ahead funk onslaught, with the band’s secret weapon Rose Stone opening up with one of the bluesiest “yeah, yeah, yeah” openings on record. After the second verse everyone drops out except for drums and trumpet for a moment of pure funk satori. The instruments suddenly drop out behind the vocalists with ten seconds left in the track, to reveal Sly and Rose trading lines with Little Sister behind. It’s a stunner.

“Everyday People,” ironically, had the longest afterlife of any song on the album, thanks to its use in the late 1990s by Toyota for an ad campaign. It deserves its fame for the great songwriting—a chugging bassline behind a low-pitched verse; the trumpet ratcheting up the tension to the chorus an octave higher, with the voices leaning in from the ninth; and the great B part with Rose Stone taunting all the haters to the tune of “Nanny, nanny, boo boo.” It’s the song that Larry Graham famously claims is the first ever use of slap bass. It’s the song that popularized the phrase “different strokes for different folks.” Is it therefore the song that we should blame for Gary Coleman’s career? I find it difficult to be too cynical while singing that chorus, though.

And then, “Sex Machine.” No relation to James Brown’s better known “Get Up (I Feel Like Being a) Sex Machine,” this is the longest track on the album, clocking in at almost 14 minutes of pure funky jam. Sly returns to the vocal harmonica technique from “Don’t Call Me…” on this track for a lengthy improvisation, with Graham’s bass alternately walking up and dropping out. A five minute guitar solo follows, leading up to a crescendo and the return of the harmonica vocals. Another solo on fuzzed out guitar follows, and the track speeds up just a notch. Jerry Martini comes in on saxophone and blows through a key change from G to A, topping out with an ecstatic high A. The rest of the instruments fade out to reveal Eric’s drums; after four measures of the pattern that he had played for the last 12 minutes, he speeds up, soloing in double time, then slowly drops the speed until he is waiting several seconds between beats and someone calls “Time!”

The album closes out with “You Can Make It if You Try,” the only track not featuring Graham on bass; Sly played the instrument on this closing track, which opens with the chorus and alternating vocals on the verses. Then a moment that caught me by surprise—suddenly we get the organ and drum part that the Jungle Brothers famously sampled to create “Because I Got It Like That.” Again, Sly peels away the instruments until it’s just drums and backing vocals, then brings the guitar, organ, and bass back in one at a time for the final coda. It’s an optimistic finale to an improbably upbeat album.

The album was Sly’s first big commercial success, hitting 13 on the Billboard pop chart and 3 on the R&B album chart. “Everyday People” hit number one the week of February 15, 1969. Sly and the band enjoyed the success, maybe a little too much. We’ll hear another one from them in a few weeks, but next week we’ll hear how some of the funk sounds on this album influenced an unlikely musician…with help from someone we’ve heard many times before in this series.

You can listen to this week’s album here: