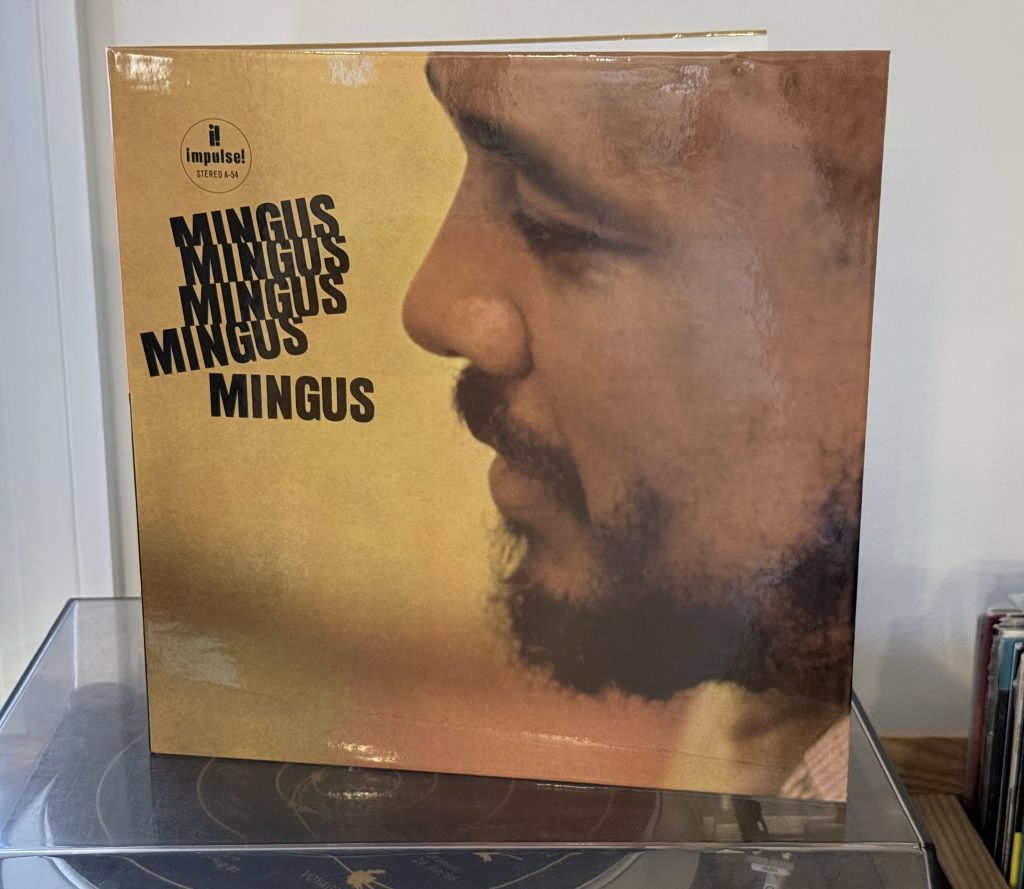

Album of the Week, January 31, 2026

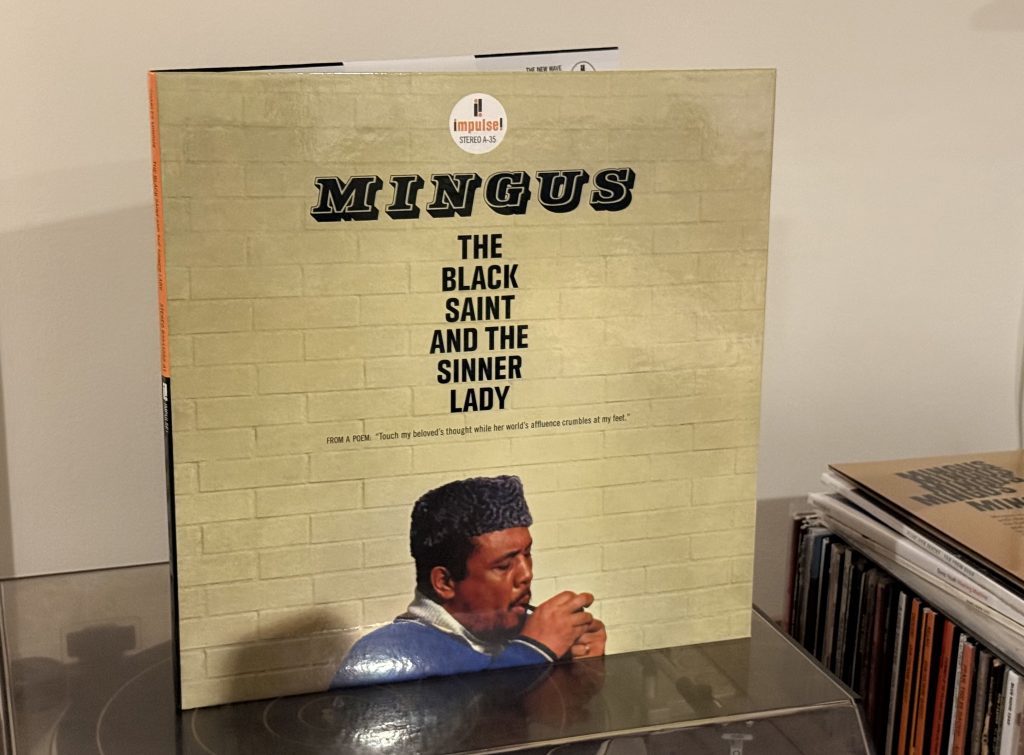

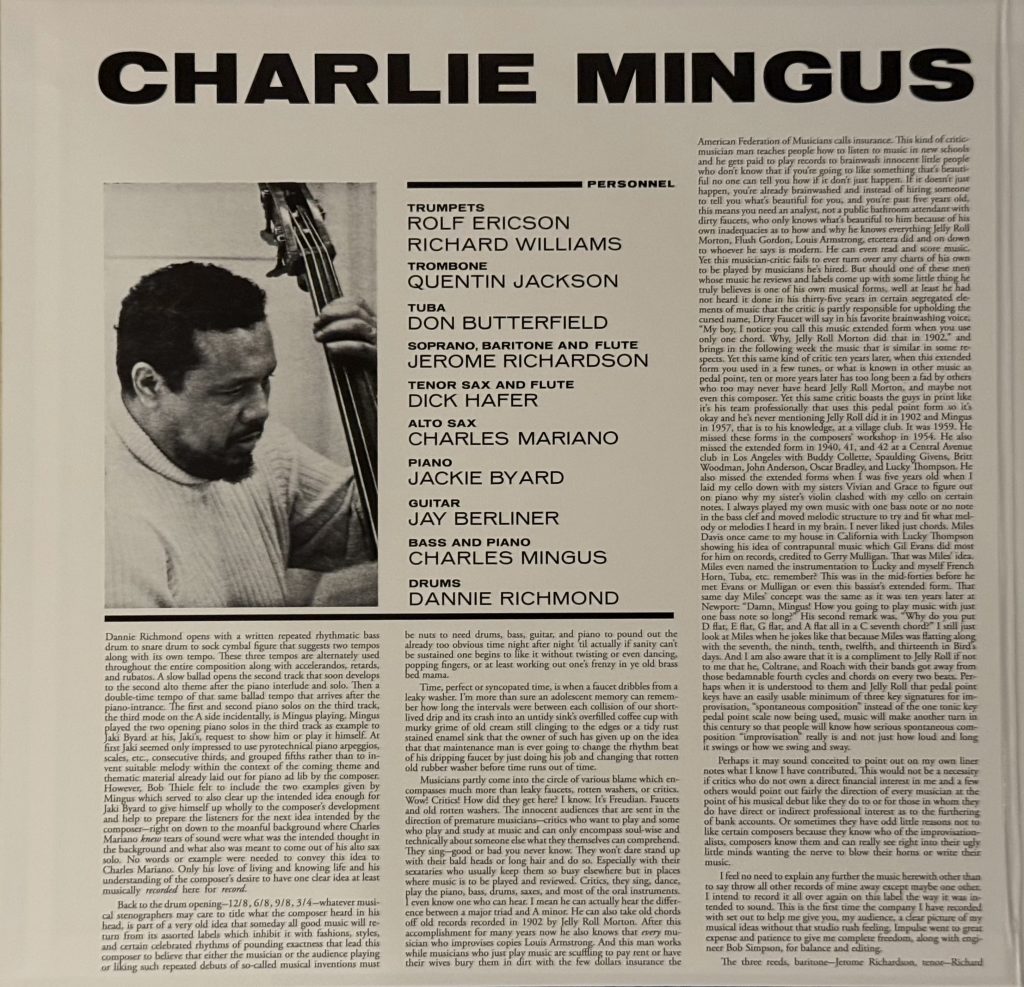

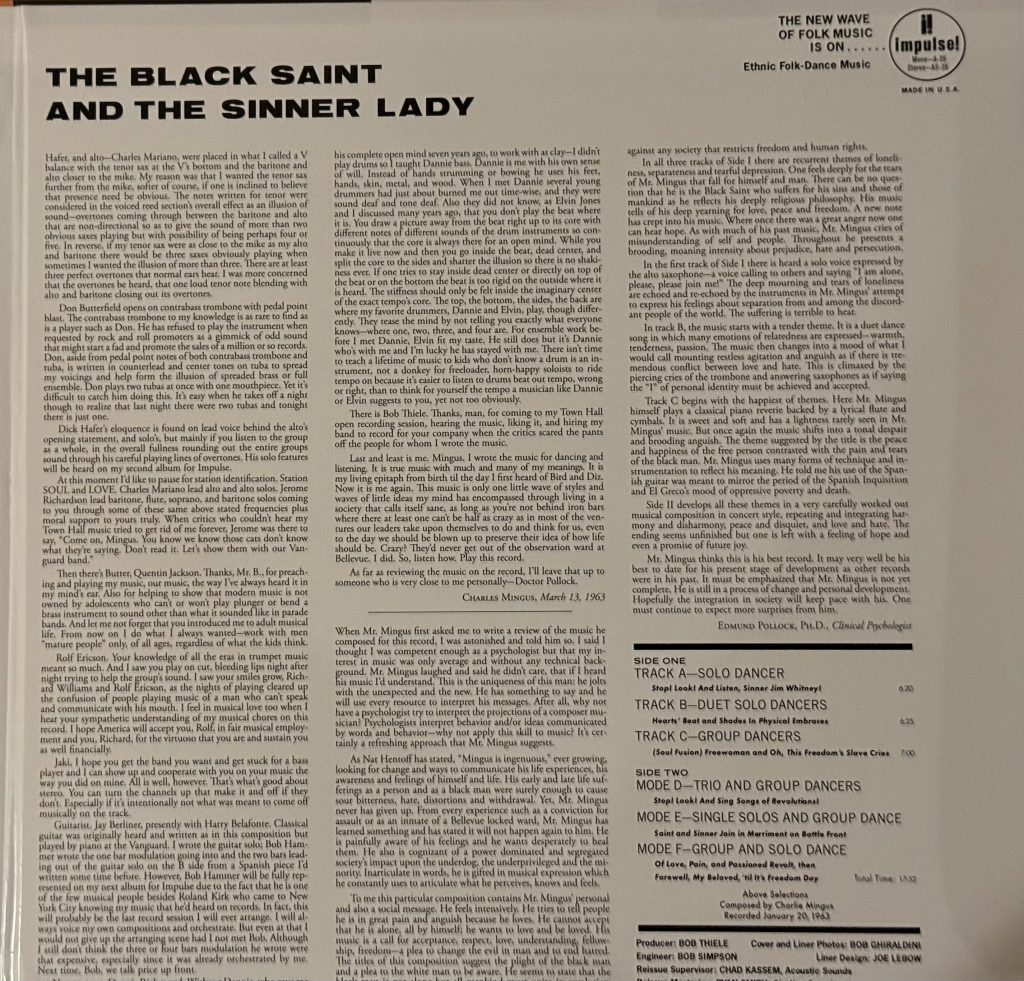

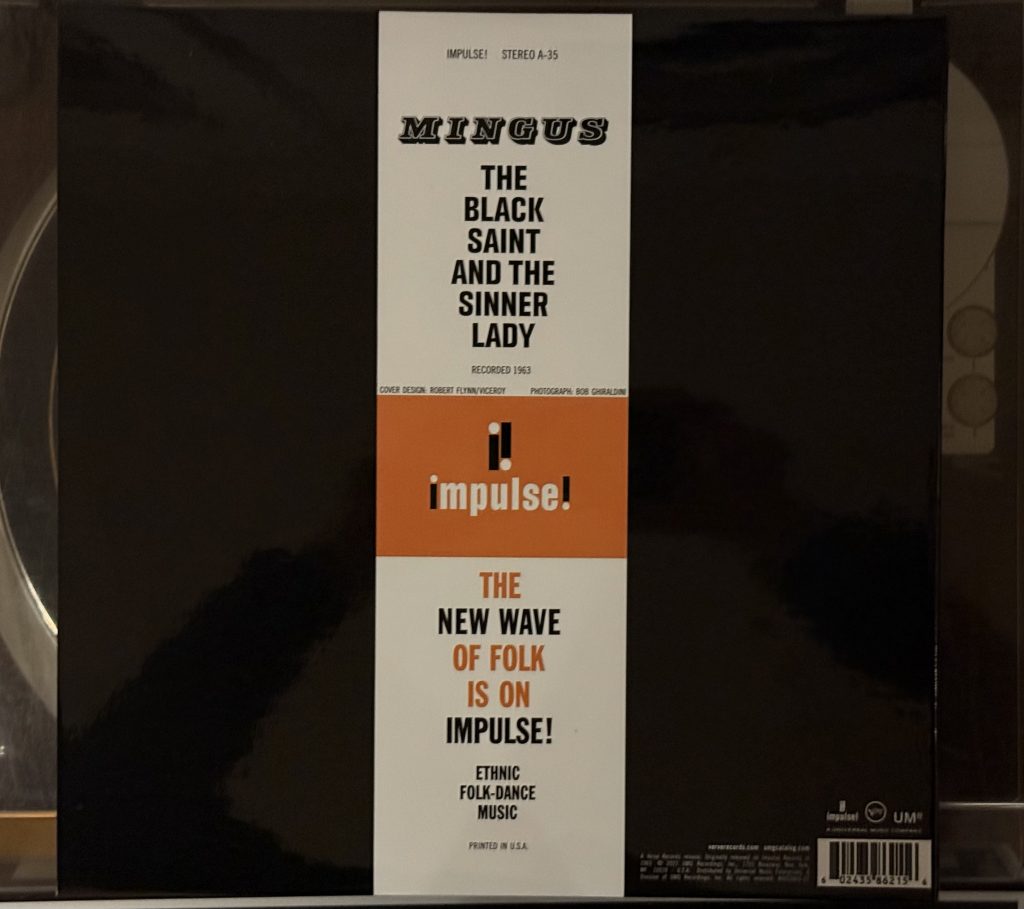

As we mentioned last week, Charles Mingus felt that he had found a sympathetic producer and label when he recorded The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady with Bob Thiele on Impulse!, and stated in the liner notes, “I intend to record it all over again on this label the way it was intended to sound.” Today’s album, Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus, is the fulfillment of that promise, with many of the same players who appeared on the earlier album and a set of career-defining compositions (and one memorable cover) filling out the grooves.

Indeed, of the band, Jaki Byard, Jay Berliner and Dannie Richmond were back (though Walter Perkins actually played drums on most of the tracks). Of the horns and reeds, almost all (Charlie Mariano, Jerome Richardson, Dick Hafer, Quentin Jackson, Don Butterfield, Richard Williams, Rolf Ericson) were returnees from the prior album, but a few new-to-us faces appeared: Britt Woodman on trombone, Eddie Preston on trumpet. And returning to the band were Booker Ervin and Eric Dolphy.

Ervin began playing with Mingus in 1958, and appeared on almost all the great bassist’s records between that year and 1961, including Mingus Ah Um and Blues and Roots, before going his own way for a few years. He played with Randy Weston and released almost 20 albums as a leader across Bethlehem, Savoy, Candid, Pacific Jazz, and most of all Prestige before his untimely death in 1970. And Dolphy, whose departure from Mingus’ band had informed the composition “What Love?” on Charles Mingus Presents, had played with Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, John Lewis, Oliver Nelson, and a whole host of other musicians before returning to Mingus’s working band for this record; he rejoined the band in earnest in early 1964.

For publishing and copyright reasons many of the tunes on the album appear with different titles than on their first appearances. Accordingly, “II B.S.”—a retitling of “Haitian Fight Song” from Mingus’s early recordings Plus Max Roach and The Clown—begins the album in swinging form, with Mingus’s fierce bass playing over a skittering of stick hits in the drums. The horns build up section by section over the bass melody, play countermelodies underneath, pull back under Jaki Byard’s piano solo, re-enter with a chugging rhythmic pulse, and then return with the slow burn once more until they build to a screaming climax.

“I X Love” is a reworking of “Duke’s Choice” from A Modern Jazz Symposium of Music and Poetry. It’s a swoony, gorgeous ballad, introduced by cluster chords and an out-of-nowhere guitar run, spotlighted with melodic solos from Dolphy and Mariano on alto sax and from the trumpet trumpet as the rest of the band splash out in seemingly (but not actually) random harmonic directions all around. There’s a spectacular clarinet moment from Dick Hafer before the lower brass take us back to the top once more. Throughout, the combination of Butterfield on tuba anchoring the bottom of the chords and Mingus’ nimble bass solos yields a deeply satisfying sonic landscape with deep harmonic range, nowhere more so than at the very end leading into the final alto cadenza.

“Celia” originally appeared on Mingus’ 1957 record East Coasting, in a sextet performance with none other than Bill Evans at the piano. Here it appears to continue the slow dance of “1 X Love,” until suddenly the corner turns and the band humphs into a fast groove led by Dolphy’s alto sax. The two modes of the tune continue to alternate, now with a tuba melody line, now with Mariano’s alto, always with Mingus’ steadfast walk alongside Richmond’s rhythmic outbursts. The work winds to an end with the lowest possible rumble from the tuba lending a faint edge of madness to the concluding chords.

“Mood Indigo” is the sole non-Mingus original on the album. In the liner notes Mingus states, “It’s absurd to put Ellington in polls. A man who has accomplished what he has shouldn’t be involved in contests. He should just be assumed to be in first place every year.” (Apparently there were no ill feelings after the drama of Money Jungle.) The arrangement is deeply felt, starting with a quiet horn chorus under Mingus’ sensitive bass; the horns drop away for an unhurried bass solo with splashes of piano and quiet brushed cymbals. The band returns for one more quiet chorus before finding their way through the end of this deeply felt tribute.

“Better Get Hit In Your Soul,” making its memorable debut on Mingus Ah Um as “Better Git It In Yo’ Soul,” is opened with Mingus’ solo bass and then the reeds playing the melody. It’s Jerome Richmond’s baritone that gets the chorus part, accompanied by wordless yells from Mingus way down in the mix that are just barely picked up by his bass direct mic. That’s Walter Perkins on the drums on this one, coming as it does from the September session that makes up the majority of the tracks. The brilliant bit of this arrangement: after Mingus sings the tag line, “Better get hit in your soul,” and the band stops, they recapitulate everything in an extended coda, this time in a swinging 4/4 rather than the fierce 6/8 of the melody. They seem likely to do it again, too, as Mingus trails pizzicato and Byard plays into the fade-out.

“Theme for Lester Young” follows “Better Get Hit” as it did on Mingus Ah Um, when it was titled “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat.” Written as a tribute to Young a few months after his death, the song proceeds as a series of statements from each of the horns over the noir-ish charts. The tune feels as familiar as a worn suit, given new life by the depth of the horn section and by Byard’s extended chords at the end.

Last, “Hora Decubitus” appears in a new title, having originally been “E’s Flat, Ah’s Flat Too” on Blues and Roots. This is blues all right and a fast one, swung by Mingus and Richardson, then the rest of the band joining in. Dolphy’s solo switches out of time for a minute before he’s joined by the rest of the group. It’s a joyously swinging dance with each member of the group improvising across the tightly arranged charts, and a coda that calls to mind all the high points from the album as Mingus gets the last word.

Mingus kept a subsection of this band together for the next year, recording a few concerts and taking a tour to Europe where they met much acclaim. At the end of the tour, Dolphy told Mingus his intention to remain in Europe. He had a series of dates booked, traveling to West Berlin on June 27, 1964 to play the opening of a jazz club called the Tangent, but he fell severely ill and could barely play. On June 29 he fell into a diabetic coma and died; stories vary as to whether doctors gave him too much insulin, causing insulin shock and death, or whether they assumed that he was on drugs and left him to die in his bed. Mingus, bereft, carried on. We’ll hear another milestone performance from after the band’s return to the States next time.

You can listen to this album here:

BONUS: The Mingus-Dolphy European tour of 1964 yielded a number of memorable performances recorded for television. This one, recorded in Belgium, has some spectacular moments of interplay between Mingus and Dannie Richmond, and truly spectacular moments between the horns and Dolphy on flute, plus a truly fantastic bit where Mingus plucks the strings of the piano in what appears to be an avant-garde improvisation until we realize, no, he’s taking a tuning break.