Album of the Week, August 24, 2024

When we began listening to Miles over two years ago, we touched on the heroin addiction that nearly derailed his career just as it was starting. We then jumped ahead to 1955 when he began recording a series of pivotal albums for Prestige that led to his fame and fortune (and a bigger contract at Columbia). But starting at the beginning of 1954, Miles was coming back, having gotten clean from his addiction and recording newly disciplined and interesting music. Prestige released the results on 10″ LPs, and then, following Miles’ departure for Columbia, reissued them on 12″ records.

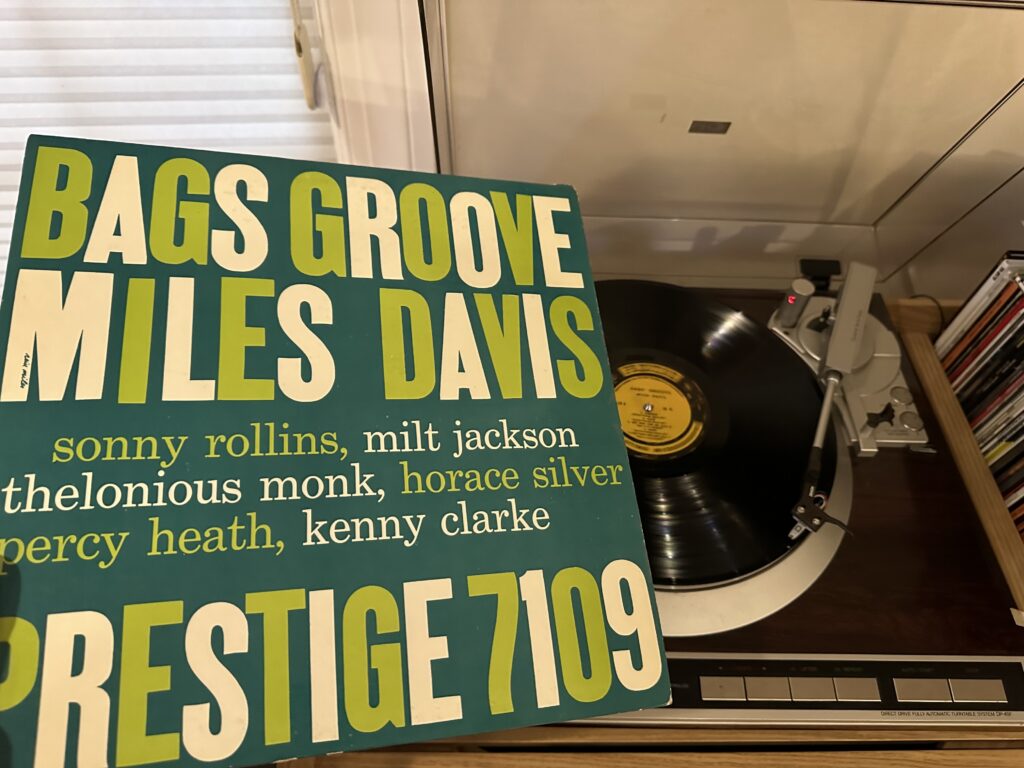

Two of those sessions, recorded June 29 and December 24, 1954 in Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in Hackensack, make up Bags Groove (the brilliant typographic album cover by Reid Miles omits the apostrophe, ducking the question of how to do a proper possessive, and I reluctantly follow suit). The players are a pretty significant who’s who. The first session (on side 2 of the record) includes Sonny Rollins and Horace Silver, while the second (side 1) features Thelonious Monk and “Bags” himself, Milt Jackson, on vibes. All tracks feature Percy Heath on bass and Kenny Clarke, a year away from expatriating to Paris, on drums.

“Bags Groove” comes in two versions, marking the first time in this blog series that we’ve run across a classic jazz LP that actually includes an alternate take. Both takes lean toward the “cool” side of Miles’ early repertoire, thanks to Jackson’s modal introduction and Miles’ Harmon mute. The liner notes by Ira Gitler say that Miles asked Monk to lay out during his solo, which must have aggrieved Monk to no end! But Monk does as asked; in the second take he drops out for the entirety of Miles’ solo, re-entering behind Milt Jackson, where he subversively adds different and unexpected chords until Bags himself drops out and Monk takes over. Hearing Monk do his thing has to be the principle pleasure of this arrangement, in fact, aside from the fluency of Miles’ solo over what would otherwise be a pretty straightforward 12-bar blues.

The numbers with Sonny Rollins are a different story. Sonny was apparently writing compositions on scraps of paper during the June 29 session, and three of his most enduring and most-covered compositions are the result. “Airegin” (“Nigeria” spelled backwards) has more than a little of the feel of “A Night in Tunisia” in the introduction, but it pretty swiftly shifts to its own thing—not yet as volcanic as it would be in another year with Miles and Trane on Cookin’, but a pretty hot groove nonetheless. The tempo is ever so slightly more relaxed here, perhaps in part due to Percy Heath, whose walking bass line sounds like it doesn’t want to be hurried.

That same sense of relaxed groove permeates the Charlie Parker-like “Oleo,” which again is a much more laid back take than that which the First Great Quintet would record on Relaxin’. But don’t tell Sonny; he and Monk get into some understated interplay during his solo, and there’s even a great moment where he single-handedly alters the chords on his way out of the solo with just one note. Monk is a little less demonstrative in this number, perhaps because no one told him not to play!

The sole standard on this session, “But Not For Me” appears in two takes, with take 2 first. Thanks to Monk, we don’t get a straight ballad, but a sort of wink at one; he doesn’t seem to accompany the other players as much as he comments on them. Rollins’ solo is a rollicking one, with more than a little swagger in its swing as he works in bits of “Doxy” into the second verse of his solo.

Speaking of “Doxy,” the third of the great Rollins standards here, Gitler calls out the “funky” character of the music; I’d prefer to call it “suggestive,” in a slightly exaggerated Mae West-style “come up and see me sometime” spirit. Interestingly, Rollins’ own solo is the only one that doesn’t feature any intimations of either hanky or panky.

We close with “But Not For Me (Take 1)”; are we suggesting that the doxy is not for us? Here the repetition of the performance is OK with me as the solos are anything but repetitive. Miles in particular takes a unique approach to the rhythm of his solo, playing a sly hemiola before dropping completely out of the last bar before Rollins picks things up. Monk is less oblique here than on Take 2, playing an unusually straight ahead solo before he develops into the idea of commenting on the other players on the last chorus. It’s a solid ending to a solid session.

Bags Groove gives us a great window into Miles the bandleader before he put his first great band together, as we get a fascinating glimpse of what an alternate quintet might have looked like (imagine Thelonious Monk on Milestones!). Next time we’ll check on some of the players that did become part of that quintet, and the one who made it a sextet, in a live setting.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

PS – A note on collecting vinyl: Sometimes you get lucky. I didn’t set out to find a copy of the 1958 second pressing of this early Miles set earlier this summer, but when I walked into the antique shop in western Massachusetts it was right there, and to my delight it was gorgeous and beautifully playable.