November 29, 2025

Remember how I signed off last week saying we were going to “take a break for some seasonal music,” bringing this run of articles on the jazz organ to a close? Wanna know who our first purveyor of seasonal music is? (Squints) Oh yeah, Jimmy Smith. Had I planned better I could have set this up as a great segue from the organ combo articles into the holidays, but as it is you’ll have to settle for an absolutely spectacular album of both jazz organ and holiday music.

Jimmy Smith in 1964, on Verve, was at the height of both his musical powers and his bankability, and Creed Taylor was not the sort of producer who was above stretching the popularity of his artist for some additional revenue via the time-honored tradition of the Christmas album. Coming off his one-two punch of The Cat and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, you’d be forgiven for expecting that Smith would take things easier on this holiday album. But with a band consisting of many of the musicians who made those great recordings, including Kenny Burrell (and Quentin Warren) on guitar, Art Davis on bass, Grady Tate (and Billy Hart) on drums—plus a whole orchestra that included Jimmy Cleveland on trombone and the elusive Margaret Ross on harp, among others—and charts by Billy Byers and Al Cohn, there was no room for slacking here. This is a seriously hot record, and a fantastic Christmas album to boot.

“God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen (Big Band version)” begins in big band fashion indeed, with a low-brass processional full of pomp and accompanied by the timpani, right up until “tidings of comfort and joy.” At which point the trumpets call a blue fanfare and Jimmy rolls in. The band continues with a “Slaughter on 10th Avenue” style take on the tune for one more verse, but then Jimmy takes the reins and plays a clean organ trio verse with Kenny Burrell and Grady Tate that is telepathically tight and funky. The horns rise up behind the trio like an incipient ambush until they take one more verse, but Jimmy gets the last word.

“Jingle Bells” is a fine and mellow tune for the trio. Check Grady Tate’s subtle explosions behind the band as well as Jimmy’s understated organ part. The slow crescendos on the two held arpeggios are the only loud part of the arrangement, which fades out just as it gets going. It’s cool—something that can’t be said for the opening of “We Three Kings of Orient Are,” which sports a full symphonic brass arrangement that’s well-nigh Mahlerian, courtesy of saxophonist/arranger Al Cohn. But then it turns the corner into a gospel shouter and we’re really off and running. I would have been pleased to hear a side-long take on the middle bit of the arrangement, but here it’s bookended by an outro version of that opening.

“The Christmas Song” is more swinging, with both Jimmy and the band in a laid back mood. The horns are swinging so hard they’re practically a beat behind, and Jimmy happily burbles bits of mood before playing a doggedly on-model melodic solo as the horns provide chromatically oracular pronouncements. A high chorus of trumpets brings us into a double-time solo wherein Jimmy stretches out over a frantic bit of Grady Tate drumming, then back to the chorus which slowly builds to a massive climax, punctuated by a chime before the final chorus.

The trumpets give us a “White Christmas” opening that could be played by the Boston Pops, key change and all, before Grady Tate takes us into bossa nova land. Jimmy’s solo is low key, in the baritone range, at least until the horns take it up a notch, at which point we get a little happy double time arpeggio, a final chorus, and a little “Jingle Bells” quote to wrap it up.

“Santa Claus Is Coming to Town” is a trio number with Quentin Wells and Billy Hart, featuring Jimmy and Quentin trading off licks. The stereo separation (guitar in the left channel, organ in the right) is the only thing that helps to piece apart the players at the beginning, so close is the harmony, especially since Jimmy is soloing without much vibrato. Quentin Wells is a bluesier player than Kenny Burrell and he leans into that here, both in his solo and in the stabs of chords he plays under Jimmy’s solo. Jimmy starts out mellow but builds intensity through his usual tricks, particularly leaning on the tonic and playing bursts of arpeggios around the edges of his solo, all the way into the fade-out.

It’s another Pops-style arrangement for “Silent Night,” complete with bells and flugelhorn, then a handoff to Jimmy and the trio who do what they do best, a brisk, unsentimental swing through the tune. The horns make like “The Cat,” briefly, in the climax of their accompaniment to Jimmy’s solo—indeed, the only thing to criticize here is that they actually overwhelm the organ for the only time on record.

“God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen (Trio Version)” starts right in, sounding a bit like Jimmy’s version of “Greensleeves.” The trio with Quentin Warren and Billy Hart swings convincingly, with Billy’s snare work so powerful that it causes a secondary rattle somewhere between the snares and the ride cymbal. Jimmy spools off riff after riff in his solo, as Quentin Warren walks around the chords, keeping the rhythm going strong. At several points, it sounds as though the group will fade out, but the producers wisely keep rolling tape as the trio lands the hottest number on the whole record at the very end. Finally as the trio returns to the opening vamp, the engineers bring down the sliders and fade it out into the dark.

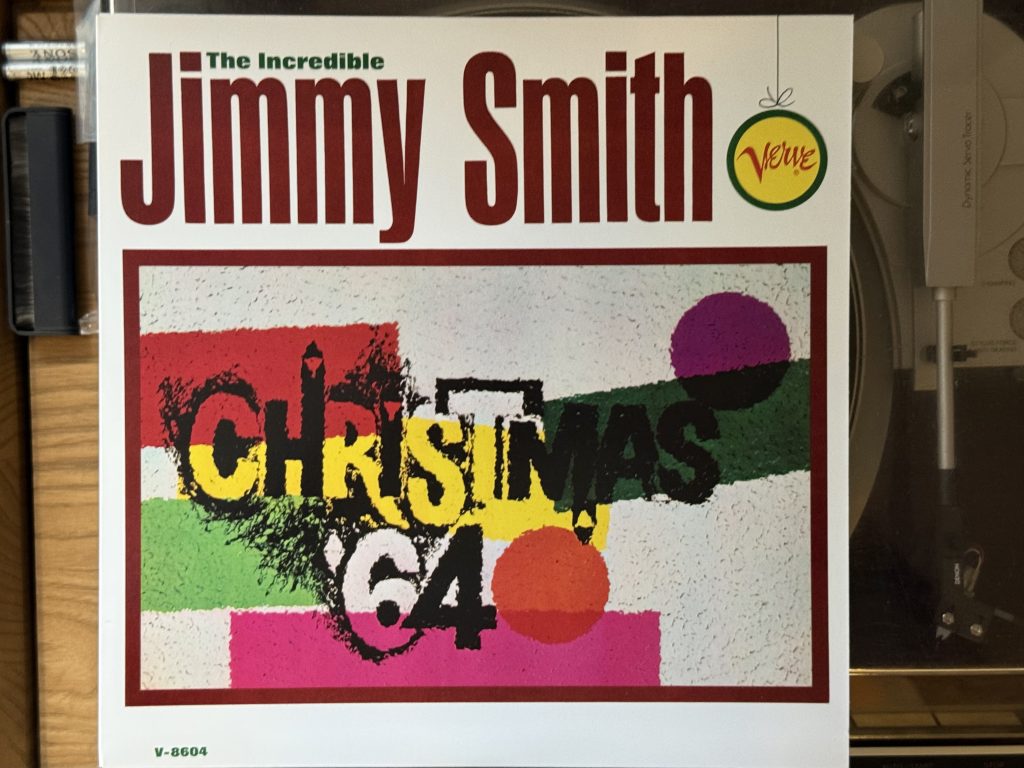

About the only thing wrong with Christmas ‘64 is the title; though it wasn’t the only Verve album to include the year in the title, it was clearly not a good choice for a title for a holiday album, which tend to sell between Thanksgiving and Christmas but can continue to rack up sales for many years. Retitled and with a new cover, the album had a long life under its new name, Christmas Cookin’, including in its CD reissue which included two other tracks, “Greensleeves” from Organ Grinder Swing and “Baby It’s Cold Outside” from Jimmy and Wes: The Dynamic Duo.

Next week we’ll stay in the jazz lane, with a holiday album by one of the players on this week’s set. You can listen to this week’s album here:

BONUS: This album and its related tracks cast a long shadow over holiday jazz records. The late great Joey DeFrancesco included a rearrangement of Jimmy’s “Greensleeves,” as “What Child is This,” on his superb 2014 album Home for the Holidays: