Not enough people talk about the through-line from spiritual jazz to smooth jazz.

That may seem like a strange, almost nonsensical thing to say, to compare Coltrane’s A Love Supreme to Grover Washington or Kenny G. Nevertheless, there’s a path there, and it runs through some artists that I’ve talked about on this blog many times before. Generally speaking, the sound I’m talking about, and that I explore in this hour of Exfiltration Radio, blends the soaring messages of hope of Pharoah Sanders’ Karma with the more cosmic sounds of the Fender Rhodes. Many of the works are more audibly optimistic, i.e. in a major key; many of them have lyrics; several have full-blown string arrangements. Some are more spiritual in focus, while others just enjoy the groove. And they almost all seem to come from the late 1960s to around the mid-1970s, with the sweet spot being from about 1969 to 1973.

That said, the overall driving force for this mix was definitely tunes that put a smile on the face and lower the blood pressure. So enjoy! The track listing:

Lonnie Liston Smith, “Expansions” (Expansions): The title cut from Smith’s 1975 album on the Flying Dutchman label, this is a darker groove than most of the songs on the show, but with that deep plea for peace at the heart of it: “Expand your mind to understand/we all must live in peace.” With a great band comprised of Cecil McBee on bass, brother Donald Smith on flute and vocals, Dave Hubbard on saxophones and Michael Carvin on drums.

Ramsey Lewis, “Bold and Black” (Another Voyage): This track from the perennially sunny improviser’s 1969 album points toward more smooth experiments, like 1974’s Sun Goddess, while providing a sunray of musical joy. Classic top-down, driving around music.

Norman Connors, “Carlos II” (Love From the Sun): Drummer, composer and arranger Connors spent most of his career in R&B and smooth jazz, but this, his third album as leader, is a fascinating, fantastic collection of straight ahead jazz with hints of spirituality poking through around the corners. A great line-up of players, including Herbie Hancock on Fender Rhodes, Gary Bartz on saxophones, Buster Williams on bass, Hubert Laws on flute, Kenneth Nash on percussion, Eddie Henderson on trumpet, and Carlos Garnett, who wrote this track, on tenor sax. Dee Dee Bridgewater guests on two tracks. The whole album is a great listen.

Azar Lawrence, “Theme for a New Day” (People Moving): Lawrence played on McCoy Tyner’s Enlightenment, Sama Layuca and Atlantis before recording his first album as leader. By 1976’s People Moving he was producing fully orchestrated sonic experiences that were full of spiritual energy and deep grooves.

Donald Byrd, “Places and Spaces” (Places and Spaces): By 1975, Donald Byrd was in a very different place than when he played on Herbie Hancock’s second album, or even his mid-1960s spiritual jazz outings for Blue Note. His 1973 album Black Byrd, produced by Larry and Fonce Mizell, was a jazz-funk fusion high point that for many years was Blue Note’s biggest selling album. Places and Spaces is the fourth of Byrd’s Mizell-produced albums, and cranks much of what made that album successful up to 11, including swooning strings and a guitar-driven hook that wouldn’t be out of place on an O’Jays record. The chant that drives the record isn’t quite P-Funk quality, but it gets the job done, and Byrd sneaks in a fully respectable trumpet solo amid the rest of the funk.

Bobbi Humphrey, “Harlem River Drive” (Blacks and Blues): Humphrey, a hugely talented flautist, also benefited from the Mizell brothers’ production on the 1973 Blue Note album Blacks and Blues, including their writing this ode to summertime cruising. The band here is mostly session players, including Jerry Peters on keyboards, Chuck Rainey on bass and the great Harvey Mason on drums, but Humphrey’s flute solo is the main thing here, a work of searing beauty in an otherwise light track.

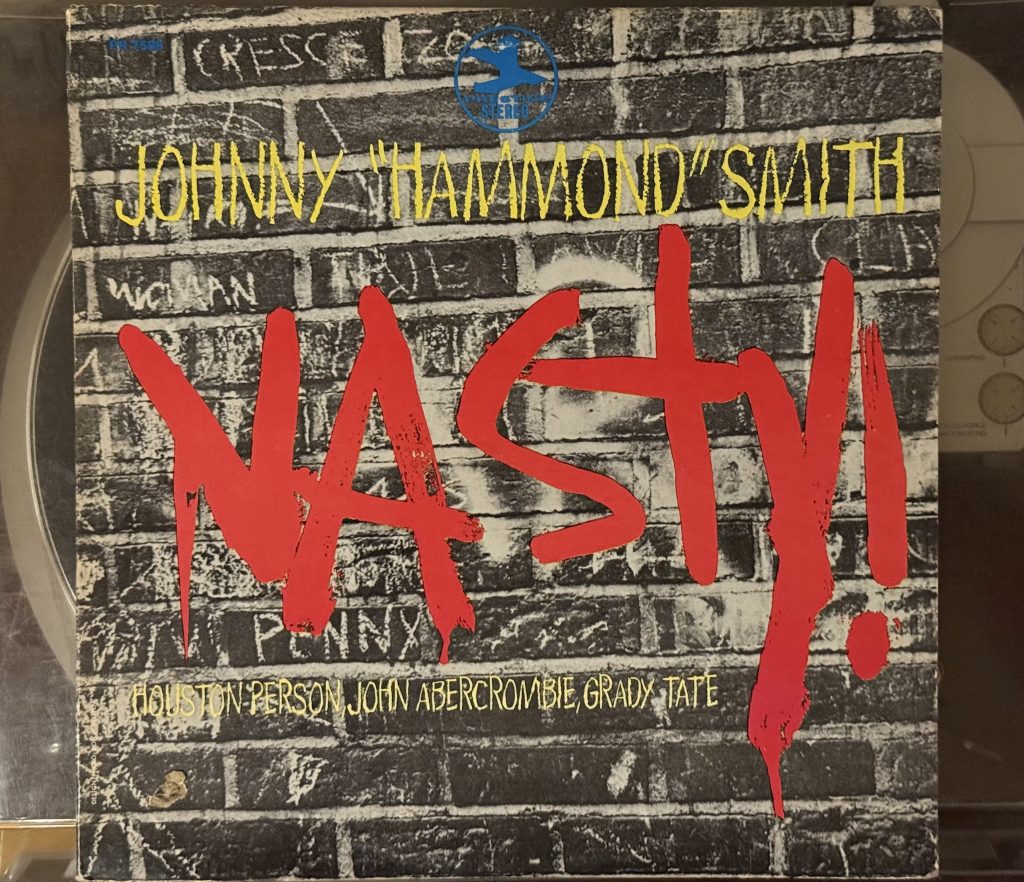

Johnny Hammond, “Can’t We Smile?” (Gears): This work, by keyboardist and sometime jazz organist Johnny Hammond, née Johnny “Hammond” Smith, not only gave me the title for this hour but kicked off the process of putting it together, after Lisa asked me why I was listening to smooth jazz; defending the track made me realize how much I liked it and how much depth lurked beneath its smooth exterior. Released in 1975 on Milestone Records, it’s another Mizell Brothers joint with Mason, Rainey, Peters, and Nash, along with trombonist Julian Priester (from Herbie Hancock’s Mwandishi band) and avant-spiritual violinist Michael White.

Lonnie Liston Smith & the Cosmic Echoes, “Rejuvenation” (Astral Traveling): Before there was Expansions there was Astral Traveling. Smith’s first album with the Cosmic Echoes was recognizably straight-ahead jazz, with much the same crew as on Expansions, but again Smith’s composition leaned forward to the optimistic and hopeful, particularly in the ebullience of George Barron’s saxophone melody. Smith’s solo similarly feels extroverted in an almost soul-shouter kind of way.

Alphonse Mouzon, “Thank You Lord” (The Essence of Mystery): Mouzon’s first album, in 1973, has tinges of the same mystery that the drummer brought to the first incarnation of Weather Report, combined with a melodic and compositional sensibility that feels akin to with Smith was doing at the same time. It also feels like some of Keith Jarrett’s 1970s work, broadly anchored in major-key tonality with a swooping saxophone shining a light in the darkness.

Pharoah Sanders, “Astral Traveling” (Thembi): Before there was Astral Traveling, there was … “Astral Traveling.” The first track on Sanders’ 1971 album, his last with Smith, was legendarily composed by the band as Smith sat and played a Fender Rhodes for the first time ever in the studio. I like this version better than the one on Smith’s later album because I feel more wonder in the playing, as though the band is together exploring a new world. It’s also a welcome view of a side of Pharoah Sanders that we don’t often think of, but he could be as gentle as he was often fiery.

Leon Thomas, “The Creator Has a Master Plan” (Spirits Known and Unknown): This brings us to the last track. Vocalist and composer Leon Thomas collaborated with Sanders on the composition of “Creator,” and both Sanders and Smith are here on this recording. This version from Thomas’s debut album gives a good view of his approach: a wide-eyed spirituality, still with some of the ululating vocal flourishes of Sanders’s recording, but overall less cosmic brimstone and more bliss.

There is nothing wrong. We have taken control as to bring you this special show and we will return it to you as soon as you are exfiltrated.