Album of the Week, November 23, 2024

As we discussed last time, Herbie Hancock went through a transition back to acoustic jazz following the success of his “Rockit” band, and with a few exceptions stayed in this lane. His former Miles Davis (and VSOP) bandmate Wayne Shorter was in a different place. Following his departure from the Miles band after Bitches Brew, Wayne cofounded one of the bedrock-foundation fusion bands, Weather Report (we listened to their first album back in 2022). He stayed with Weather Report and had a fascinating side career as a sideman to Joni Mitchell (with whom he recorded 10 albums) and others (that’s him on Steely Dan’s “Aja” and Don Henley’s “The End of the Innocence”). And he continued to record as a leader.

In retrospect, his albums and original compositions in the 1970s and 1980s had some common characteristics, though they were all very different on the surface: strong, if quirky, melodies, combined with rich orchestration—though sometimes the “orchestra” was a bunch of synthesizers. There were high points, like his duo album 1+1 with Herbie Hancock, but there were also some puzzles, like Phantom Navigator, recorded primarily with synthesizers the year after Weather Report’s dissolution and received poorly by critics. But underneath the puzzling production choices were still some of the Shorter trademarks, including new compositions based around the familiar themes of exploration to the edge of space and beyond.

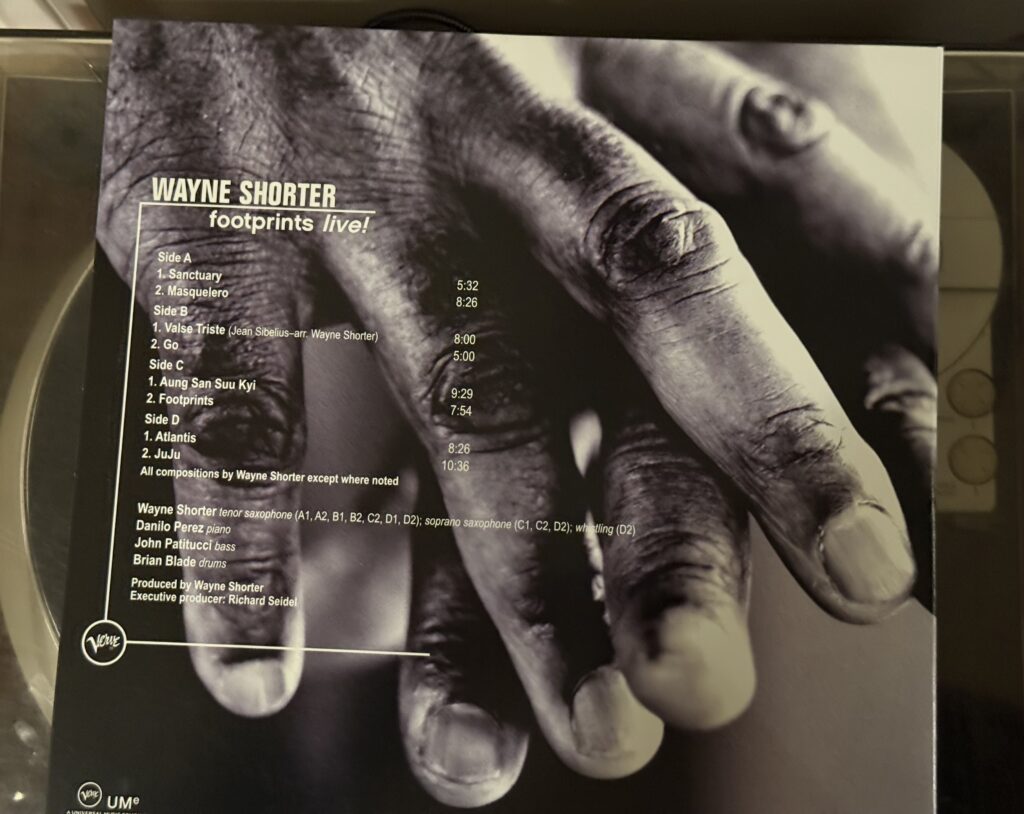

So in the early 2000s when he started touring with the Wayne Shorter Quartet—the first time in his over forty-year career that he had a steady ensemble named after himself!—people started taking notice. And the quartet, also known as the “Footprints Quartet” following this first appearance in a set of live recordings released in 2002, was worth listening to. We’ve met Danilo Pérez as the bandleader on Kurt Elling’s Secrets are the Best Stories; here the pianist was in the full flower of his career, having joined the faculty of the New England Conservatory and in demand both as a performer and a composer. Bassist John Patitucci had played extensively with Chick Corea in both acoustic and electric settings, as well as with Herbie Hancock. And drummer Brian Blade was in demand as a sideman for artists as various as Joshua Redman, Brad Mehldau, and Emmylou Harris; immediately prior to joining the group he appeared on Norah Jones’ debut Come Away With Me. The group joined Shorter on a series of European jazz festival performances (Festival de Jazz de Vitoria-Gasteiz, Jardins Palais Longchamps in Marseille, Umbria Jazz Festival in Perugia) that took a spin through Shorter’s entire career. But this wasn’t a conservatory act; it was an act of revolution.

“Sanctuary,” a track from Bitches Brew, begins with a haze of cymbals and a figure in the bass, then a repeated figure in the high octaves of the piano and an almost imperceptible low note on the tenor saxophone. Shorter rises in prominence in the track, playing a series of diminished minor arpeggios, and Pérez immediately responds with a stronger attack; throughout the players sense each others’ energy and support or even egg it on. Shorter plays the melody as a quiet improvisation in a series of two- and three-note patterns, over a constantly shifting chordal landscape in the piano and locked-in drums and bass from Blade and Patitucci.

The song doesn’t end so much as abruptly crash into “Masqualero,” which is signaled by the descending figure of the theme. The arrangement at first appears to be chaos, with the different players all going in slightly different directions from the opening. However, within a minute both Shorter and Pérez have locked into a slightly Latin rhythm, punctuated by recaps of the theme that you gradually come to realize are the organizing factor, separated by stretches of solos. … Well, the recaps of the theme and a gradually rising tide of intensity, led by Pérez’s piano. And then at about the halfway point, the band seizes onto a new melody, one that surges back and forth (and is a little reminiscent of Nirvana’s “Something in the Way”) before soaring into the stratosphere with Shorter’s soprano sax, at last taking flight. The rhythm section finally settles into a massive groove, one player shouting to another over the rolling thunder of Blade’s drums until they reach a final recapitulation of the theme.

“Valse Triste,” an arrangement of a Sibelius tune that Shorter first played on his 1965 recording The Soothsayer, is a genially shambling waltz tune in which the band pulls out some brilliant bits—imitative piano that follows Shorter’s cascading notes, drum work that seems to blend New Orleans drum tones and silvery cymbals in equal proportion, and a rock solid anchoring bass that underpins while moving the arrangement forward. By the time you notice all the parts working in concert you realize that they’ve left Sibelius far behind, just in time to find him again. When Shorter returns, it’s with a feathery, searching solo that seems to dart above the waves as they crash on the shore, and then soar out to sea.

“Valse Triste” segues seamlessly into “Go” via an introduction on the piano. We’ve met a version of this Schizophrenia-era tune before, as the melody to Kurt Elling’s “Stays”—one wonders if Danilo Pérez brought him the tune. Here the quartet delicately supports Shorter as he essays the melody across multiple verses, with Pérez exchanging harmonic ideas with Shorter, Patitucci both anchoring the tonality and arpeggiating around the corner to see what comes next, and Blade staying in the background, providing only touches of emphasis and ultimately stepping back to let the rest of the ensemble wind up the tune into silence.

The band propels “Aung San Suu Kyi” with a brisk syncopation, approximately 50% faster than Shorter’s rendition of the tune on 1+1. Patitucci’s bass is especially powerful here in a subtle but funky line that hints of a power beneath the simple melody. Pérez takes an angular solo in which Shorter makes gnomic observations, at one point triggering a burst of laughter from the rest of the band. Shorter finds a secondary melody that seems the inverse of the main theme as the rest of the band locks into another one of the massive grooves like the one they found on “Masqualero,” before the final recap.

Shorter then rips off the theme of “Footprints” at approximately the Miles Davis Quintet’s tempo as the forward motion leaps from Pérez to Patitucci to Blade. As each one pauses for breath the next member of the quartet pushes the theme forward. Shorter seems to comment cryptically on the tune with gnomic asides, even essaying a snippet of “Rockabye Baby,” before settling on a motif that feels like a major-key extension of the last four bars of the original theme. Again the band swarms on the newly improvised moment as Shorter dives and pulls up one melodic idea after another. The ideas end in a strangely tender place as Shorter’s saxophone tails off on a high note with Pérez supporting him.

“Atlantis” makes an appearance from Shorter’s 1985 album of the same name. It’s played here as a ballad with a Latin tinge and a muscular bass line. The band reaches an early summit collectively about three minutes in, but Shorter keeps exploring, and ultimately lands on a tune that climbs and circles, ultimately landing on the supertonic, where the piece ends with Pérez striking the strings of the piano. The work flows directly into “JuJu,” where Patitucci plays an arco melody over whistling by one of the band members. Blade plays a heavy funk beat as the players shout to each other and we realize that we’ve been in three all along, as Shorter limns the melody. He steps back as Patitucci and Pérez exchange snippets of the melody, ultimately finding a still quiet rendition of it. When Shorter re-enters, he freely improvises a melody both delicate and fierce before returning to the theme, which climbs up octaves before he locks back into a groove with the band, returning once more to the theme with a climactic outpouring of energy before Pérez winds things down to a finish.

By returning to the quartet format, Shorter found an ideal group to carry forward both his compositional ideas and his improvisational explorations. He would continue in this format, and with this group, almost to the end of his life, with varying emphasis on absolute freedom and composed exploration. We’ll hear another step on this journey next week when we bring this series to a close, for now.

You can hear this week’s album here: