Album of the Week, January 9, 2026

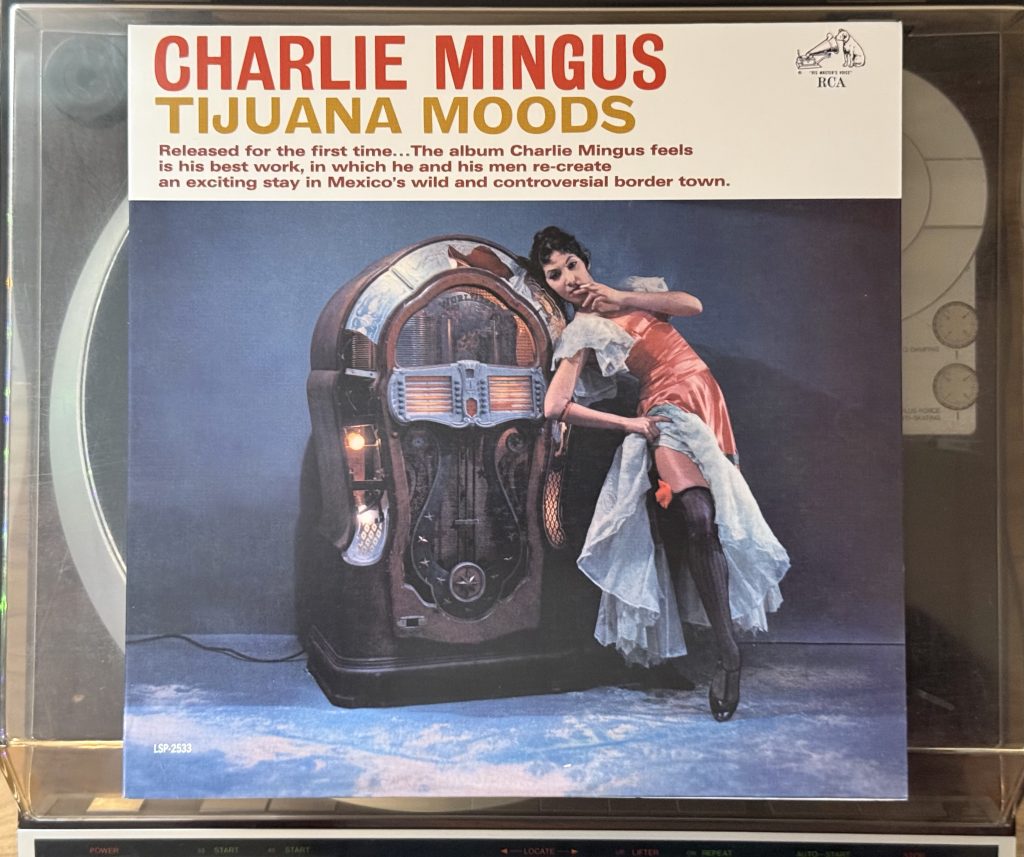

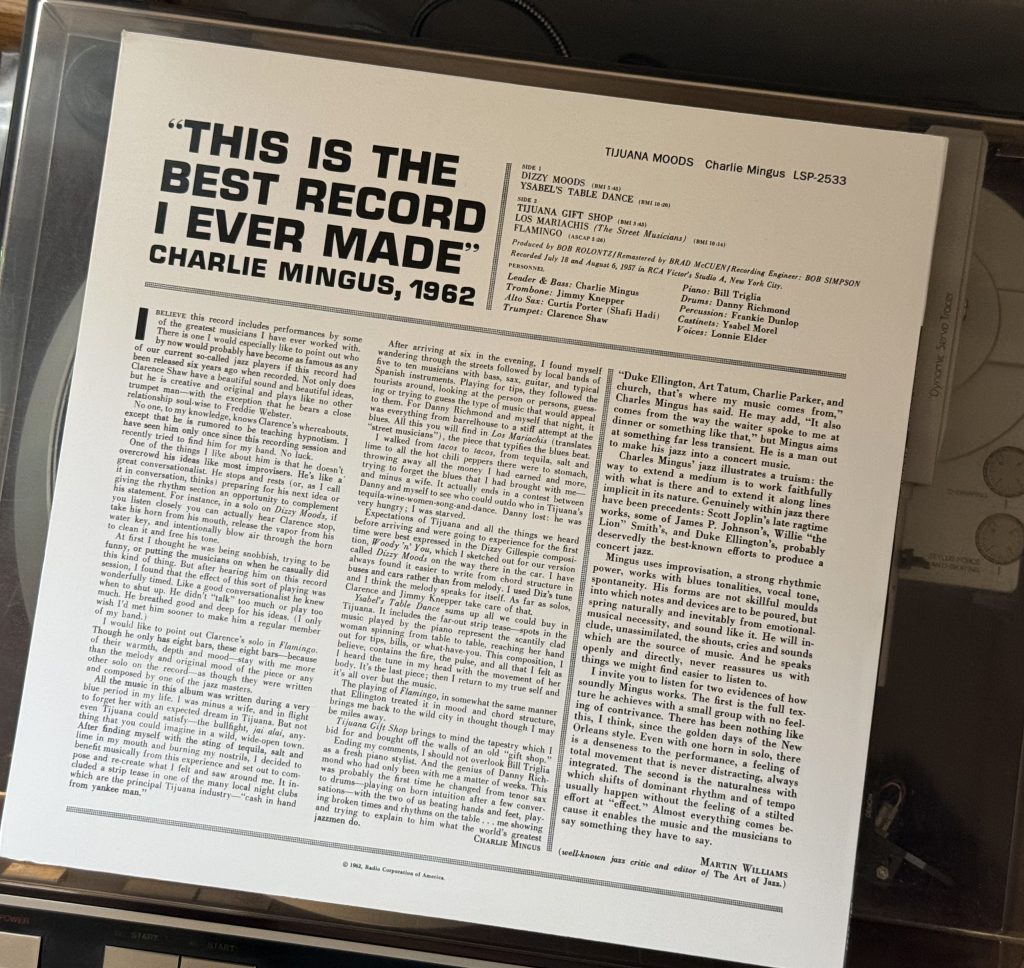

The hazard of writing about jazz records is that you inevitably hit the question: do you write about the records in the order they were released? Or in which they were recorded? This makes a big difference in the order, as many labels would sit on recording sessions for years. Prestige practically made a business plan out of this, recording many sessions with Miles, Trane and others and then releasing the albums when the artists had grown famous—sometimes years later. The same thing happened with today’s Charles Mingus session; recorded in 1957 by RCA Victor, it didn’t see the light of day until June of 1962, following one of his most eclectic and eccentric albums, Oh Yeah.

The group heard on the album is a mix of Mingus stalwarts, including Dannie Richmond on drums, Clarence Shaw on trumpet, Jimmy Knepper on trombone, and Shafi Hadi on alto and tenor sax, all of whom performed with Mingus through the 1950s and 1960s; and percussionist Frankie Dunlop and pianist Bill Triglia, both of whom racked up their sole Mingus recording credits on this album. Special note should be made of the contributions of actor and playwright Lonnie Elder, providing “luxury casting” in the blues singing on “Los Mariachis,” and especially Ysabel Morel, playing castanets and providing yelps and cries as a flamenco table dancer in her sole recording credit. The album provides a phantasmagorical journey through the South of the Border town through Mingus’s originals and highly idiosyncratic arrangements.

“Dizzy Moods,” a Mingus re-arrangement of Dizzy Gillespie’s “Woody’n You,” opens us up with a cockeyed horn fanfare followed by short solos from Mingus, Richmond, and Triglia. The band plays the first verse together, getting an atmosphere highly reminiscent of Mingus’s “Haitian Fight Song” in places. Knepper, Hadi and Shaw all turn in ripping solos, but what ultimately what sets this apart from other large-ensemble jazz of the 1950s (especially Miles and Birth of the Cool) is the feeling that the group’s playing might edge into chaotic noise at any moment. Indeed, there’s enough menace in the playing to recall Mingus’s penchant for fighting, whether the story about him and Juan Tizol that we talked about last week, or his turbulent relationship with other musicians—including some on this record.

“Ysabel’s Table Dance” is a tequila-tinged tour de force of a composition, the rhythm alternating between Morel’s castanets, sounding like a sped-up toreador battle, and the band’s more relaxed swing temp0. Mingus accompanies Morel’s initial foray with an emotive solo, played both arco and pizzicato like a large cello. There are what seem to be hard cuts from one section to another,1 as Hadi, Shaw and Knepper all take brief statements of the melody at something approaching warp speed. A melancholy solo from Triglia stops time, and the band returns in a swinging slow four. The final few minutes find a synthesis of the band’s melody and Morel’s Iberian dance, with Mingus accompanying the castanets with a col legno riff of his own.

“Tijuana Gift Shop” opens with a brisk riff by Richmond and Dunlop, followed by a playful melody in the horns that seems to embrace the wild energy of the town; Mingus’ notes state it was inspired by a tapestry that he “bought off the walls of an old ‘gift shop.’” The band engages in some inspired collective improvisation, with hardly any single-horn solos until Hadi’s lovely melody at the end, sounding a closing cadence reminiscent of Miles’ Sketches of Spain (still three years in the future when this album was recorded!).

“Los Mariachis” evokes the visitors walking through the streets of town until they are stopped by a group of horns playing a sad ballad. Mingus’s bass propels a slow blues beat into motion, with Shaw and Knepper limning the blues melody as Lonnie Elder provides an inchoate blues cry. There’s an abrupt shift of mood courtesy of Shaw’s trumpet as the band strikes up a more traditional mariachi melody, albeit one with the horns playing in multiple musical motifs all at once. We return to the ballad once more before launching into a more modern dance, which becomes a tender moment scored by Knepper and Triglia. The blues and the modern dance alternate through to the end of the track, but ultimately the blues wins out.

Ted Grouya’s “Flamingo,” given a far more expansive reading here than when I last wrote about it on Wynton’s Standard Time Vol. 3, has its melody sketched out by Shaw and Hadi in a completely free moment, the players pulling the melody out of the late night air. Knepper plays a heartfelt solo on the bridge, punctuated by a dissonant blast from the horns as the tune turns the corner into the chorus. The overall impression is of a quiet early morning rendezvous, with the romance punctured by bursts of sound spilling out as a door opens and a patron reels into the night air, bringing Mingus’s tour of the wild town to a close.

Mingus is said to have stated, on the occasion of Tijuana Moods’s release in 1962, that it was “the best record he’d ever recorded.” While that is highly debatable (Mingus Ah Um, anyone?), it does provide a highly coherent, if kaleidoscopic, view of his compositional talents in these longer-form songs. As noted, many of the musicians began longer journeys with Mingus with this album; Dannie Richmond in particular had switched to the drums from the saxophone shortly before this recording. Not all the relationships would last; Mingus notoriously punched Knepper in the mouth during an argument later in 1962, damaging his teeth and his embouchure, an injury that affected his playing and required years for him to recover from. We’ll hear another notoriously argumentative—but brilliant— Mingus recording next time.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

BONUS: There are relatively few live performances of the material from this album, making this 1964 Copenhagen performance of “Ysabel’s Table Dance” (minus Ysabel, and castanets!) highly interesting:

- A 1986 reissue notes that there are hardly any complete takes from the original sessions; the tracks were assembled from something like 21 takes of the five songs. ↩︎