Album of the Week, March 9, 2024

Inside the gatefold cover of the John Coltrane Quartet’s early 1965 release A Love Supreme are two passages by Coltrane. One is an epistle from the saxophonist to the listener that is equal parts confessional and prayer. The other is a prayer to God. Both provide the missing ingredients that would tip the alchemical brew being created by the Quartet over into something legendary.

A while back, in a review of Steamin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet, I wrote: “Miles had struggled with heroin early in his career… Unfortunately, his saxophone player, John Coltrane, was still in the thralls of the drug, and left after these recording sessions for a period. He would get clean in 1957 (which is a story for another day) and rejoin the band in 1958.” In these liner notes, Trane writes: “During the year 1957, I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life… As time and events moved on, a period of irresolution did prevail. I entered into a phase that was contradictory to the pledge and away from the esteemed path; but thankfully, now and again through the unerring and merciful hand of God, I do perceive and have been duly re-informed of his OMNIPOTENCE… This album is a humble offering to Him. An attempt to say ‘THANK YOU GOD’ through our work, even as we do in our hearts and with our tongues.”

What is sometimes missed in the reading of A Love Supreme as gratitude is that Trane was giving thanks not just for one salvation but for two: the 1957 awakening that saved him from heroin, and an unnamed second event (or events) that helped him along the path. The album, therefore, is not a commemoration; it’s a practice of gratitude, and prayer, and an acknowledgement of the mystery of higher power.

Part of the power of A Love Supreme is that it retains the searching that is the core of Trane’s greatest work, rather than settling for simple praise. Indeed, “Part I: Acknowledgment” seems to be at once solidly in one key and in every key at once. It opens with a pentatonic statement from Trane and what appears to be a cluster of B major chords from McCoy Tyner under a flurry of cymbals from Elvin Jones and a bowed tonic drone from Jimmy Garrison. When Garrison enters a moment later, though, he drops down a fifth and plays the famous opening in F minor:

Trane enters on the fifth, still in F but now playing with mixolydian mode, and Garrison stays in this tonality throughout. Trane’s solo stays grounded here as well, though it does explore modal connections. At the end of his solo, he takes the passage up an octave, overblowing a bit to mark the top, then runs back down and scales up chromatically. He seems to bring his solo to resolution, but then at 4:58 in the track, something funny happens. Biographer Lewis Porter notes that the score for the work says, “Move in 12 keys — move freely in all 12 keys — solo in 12 keys.” And that’s what Trane does — he takes the four note motif and moves through all twelve minor keys as Tyner stays with him and Garrison stays grounded.

He then returns to the theme, and then something that had never happened in his work enters: we hear the sound of Trane’s voice, chanting “A Love Supreme” on the tune of the motif. There are fifteen repetitions of the motif in F minor, followed by four in E♭ minor, as the chanting fades out and Garrison plays a different but related motif, from the fifth up to the seventh and octave. According to Porter, the chant is an overdub, indicating again that Trane had a specific idea of how he wanted the performance to go and that he was looking for a particular conception. Trane seems to invoke a vision of a God who is everywhere at once, or of an angel looking in all directions at the same time yet is grounded in one place.

Garrison opens “Part II: Resolution” in E♭ minor, picking up the key from “Acknowledgement.” He uses a different technique here, sounding a chord on two adjacent strings at once to sound out something like a prophetic utterance. When Trane enters, he is in full apocalyptic mode, playing the melody four times and then yielding to Tyner for the solo. Tyner is in classic form here, soloing in different rhythms and exploring adjacent voicings as he drops bombshell chords with his left hand, all while Elvin Jones pours gas on the fire. Trane returns to state the melody but doesn’t really get a full solo here. While very much a piece of the whole, “Resolution” is the one movement that feels like it could be picked up and dropped onto Crescent or another mid-1960s Trane album. More than anything else this points out the consistent theme of searching that stretched from his early works through to the very end.

“Part III: Pursuance” opens with a propulsive Elvin Jones solo that breaks everything open, leading into Trane’s statement of the tune. Tyner again takes first solo, alternating between following Trane’s blues and quoting bits of the “Acknowledgement” motif. As Porter says, this quartet owned these high velocity treatments of the blues, and no moment represents that statement so much as Tyner’s alternate melody that he states just before Trane enters to take his solo. Trane is jet propelled here, keying off Jones’ fierce energy, and tireless; after two and a half minutes of his solo, he starts to overblow the reed, getting a mighty Pentecostal honk, before he and Tyner step back to let Jones’ volcanic energy erupt one more time, then fade back. Jimmy Garrison now takes a solo that recapitulates moments from both “Resolution” and “Acknowledgement,” eventually landing back in C minor.

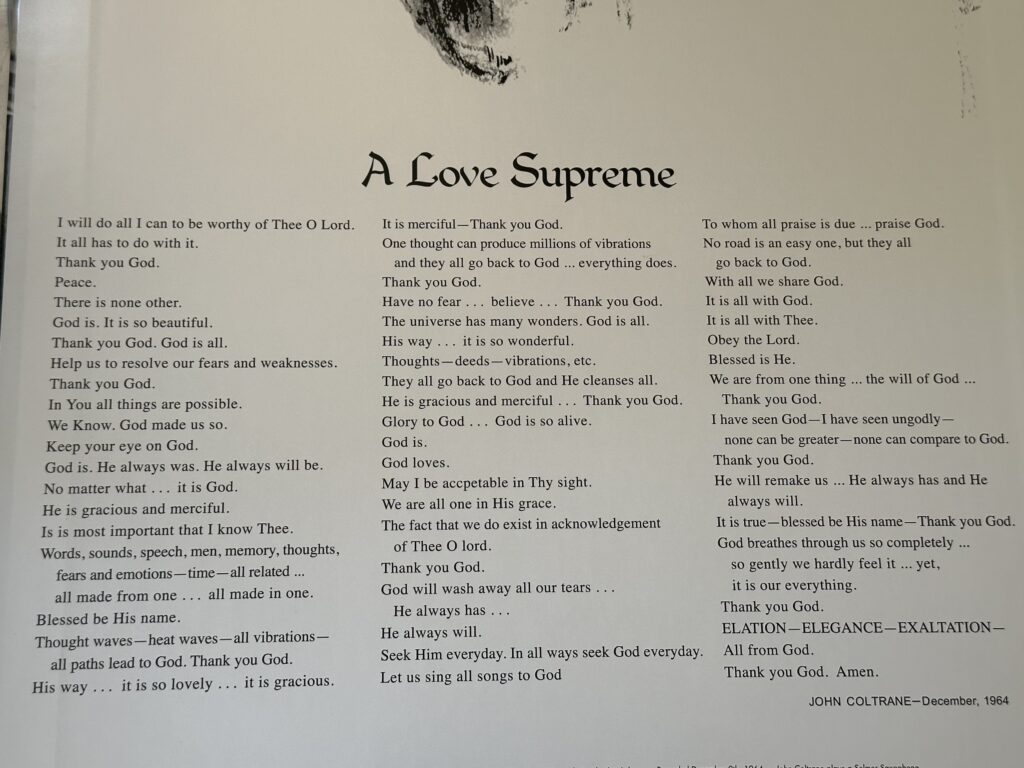

“Part IV: Psalm” is many things: a culmination and coda of the suite; a free, melodic solo by Trane; and, in all likelihood (as documented, again, by Porter), a direct translation, note-for-syllable, of the poem that Trane places on the other side of the gatefold. It is at this point in the suite that the purpose of the ballad albums that the Quartet recorded from 1962 to 1963 becomes clear. Without that immersion in melody, “Psalm” (and its spiritual predecessor, “Alabama”) could never have happened. The quartet provides powerful accompaniment underneath Trane’s recitation, Jones on timpani, Tyner with washes of block chords, Garrison with a long subterranean rumbling. Trane concludes with a reading through the horn of the final words of his poem, “Thank you God. Amen,” and then a brief recapitulation of the opening flourish of the work.

One of the reasons that A Love Supreme still seems to connect with listeners all these years later is surely this combination of mystical reach and absolute accessibility. The “a love supreme” chant at the beginning is a prayer, a mantra, and a hook that catches the listener. Even without the words, the strongly rhythmic playing of Jimmy Garrison, in particular, throughout the album gives the listener something to catch onto amid the blistering improvisation coming from the quarter.

Regarding that second salvation event I mentioned earlier. While unclear whether it’s connected to Trane’s straying “away from the esteemed path,” in the summer of 1963 he left Naima, his first wife, and his adopted daughter Syeeda (born Antonia) and stayed “in a hotel sometimes, other times with his mother in Philadelphia. All he said was, ‘Naima, I’m going to make a change.’” Around this time, he met the pianist Alice McLeod, who shared his interest in spirituality, and their paths would remain connected for the rest of his life, both personally and in his music. We will hear more of her music later.

He was working with other musicians as well. In fact, on December 10, 1964, a day after recording the tracks that became this album with his Classic Quartet, he recorded it again, with the addition of second bassist Art Davis (last heard with the quartet at the Village Gate) and saxophonist Archie Shepp. Both are thanked in the liner notes for their work “on a track that will regrettably not be released at this time.” Shepp in particular would go on to be a part of Trane’s sound in the following years. And Trane would take A Love Supreme not as a finished blueprint, but as a starting point to build even higher and stranger things. We’ll start to hear that next week.

You can hear this week’s album here:

Postscript: Later in 1965, Franzo and Marina King heard Coltrane play “A Love Supreme” in one of a handful of live performances. It moved them so deeply that they established a church in their home city of San Francisco dedicated to the spiritual teachings of Coltrane, known today as the St. John Will-I-Am Coltrane African Orthodox Church, or simply the Coltrane Church. They’re still going today, and Trane’s “A Love Supreme” poem is their central text.

5 thoughts on “John Coltrane, A Love Supreme”