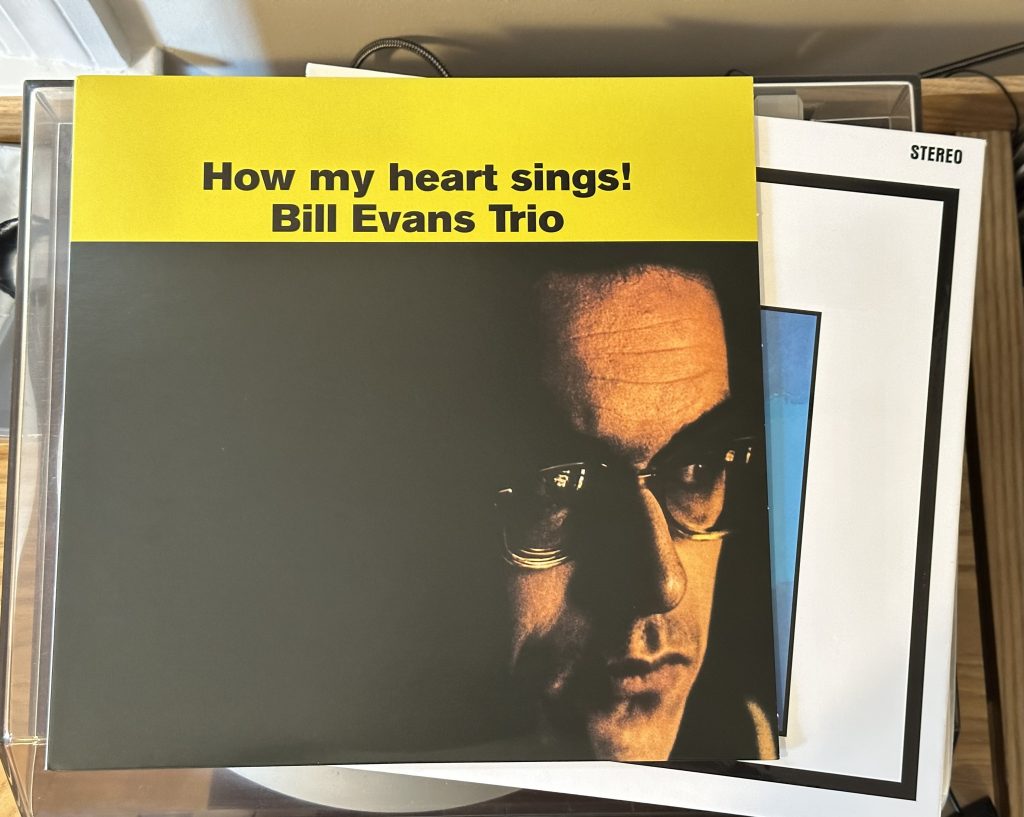

Album of the Week, January 28, 2023

Producer Orrin Keepnews said in the liner notes to Bill Evans’ How My Heart Sings, “This project was the first time I had set out to record two albums by the same group at the same time,” referring to the album of ballads that came from these same sessions, Moon Beams. The theory behind this album was a set of more up-tempo songs to accompany the unusual all-ballads format of the accompanying recording. As Evans himself noted, “the selections presented here are primarily of the ‘moving’ kind, though there is in the trio’s approach to all material the desire to present a singing sound.”

Whatever you call it, this second recording from the May 1962 sessions, not issued until January 1964, is unusually buoyant. But it’s not extroverted; it rings with a quieter joy. You can hear it from the beginning, where Evans opens Earl Zindars’ “How My Heart Sings” with a gentle swing that leans against the syncopation of Chuck Israels’ bass. Drummer Paul Motian is a little more present here than on Moon Beams, underscoring the shift from 3/4 to 4/4 in the second chorus, but he still stays mostly in the background, setting the stage for the dialog between Evans and Israels.

“I Should Care” leans into the rhythm harder, with Motian swinging against Evans through several choruses before falling back behind Israels’ solo. Here the bassist underscores Evans’ point about really singing the line, as the solo is lyrical and all melody. Evans plays with the beat throughout this one, shifting emphasis to the second and fourth beats, especially in the last chorus.

We’ve heard Dave Brubeck’s great standard “In Your Own Sweet Way” before, but here Evans puts his own stamp on the tune, taking it faster and playing with the beat in the bridge, then briefly departing from the gentle swing of the original into a racing second melody, as though bursting into a second song in the middle of a first. Chuck Israels’ solo takes the melody down into the bass depths and fragments it further; when Evans steps alongside him he tosses the fragments back and forth with the bassist as they go.

“Walking Up” is an Evans original, with more than a little of the feel of John Coltrane’s “Countdown,” from Giant Steps. But when he turns the corner (or maybe reaches the landing?) we’re suddenly in a different environment. Perhaps we’ve walked to the top of a bridge and that’s a ray of sun peeking through the fog? At any rate, we’re playing with meter again, moving from straight four into a syncopated off-beat, and it’s fascinating.

If you’re going to play “Summertime” and make it your own, you’d better have some good ideas to share. The version on this record, again, shares some DNA with a Coltrane recording, in this case the version of the great Gershwin tune on My Favorite Things. Both recordings feature a rhythmic motif around the modal suspension underpinning the verse, but where Trane’s version has the beat in McCoy Tyner’s piano, here it’s given to Chuck Israels, who opens the track with the motif and never puts it down. Evans’ version swings more than Trane’s, due in large part to Motian’s skillful fills. This is probably the one track where Motian steps out of the background and you can really hear all of the things he’s got bubbling away under the others.

“34 Skidoo” is the second of three Evans originals on the album, and the jauntiest by far. Sliding in and out of different meters, Evans and Israels take turns syncopating the tune and perform some incredible handoffs between their turns at the wheel. The momentum continues through Cole Porter’s “Ev’rything I Love”; the tune leans closer toward ballad status than most of the numbers in this set, but when Evans comes out of the first chorus he takes lyrical flight.

“Show-Type Tune” brings us out with another Evans composition. A wistful opening on the piano is followed by a metaphorical “squaring of the shoulders” and a more forthright, lyrical verse. The most extroverted performance on the album, the track features Evans pulling out trick after trick in his solo, shifting chromatic scales at the end, and seemingly taking flight at the end. It is a heck of a closing number from such a deeply introverted performer.

The two albums recorded during the May 1962 sessions re-established Evans as a force to be reckoned with, and put a capstone on his time with Orrin Keepnews’ Riverside Records. The following year saw him move to Verve and producer Creed Taylor, where he would make some deeply original recordings — as well as a fair amount of dreck. We’ll hear some of the more original and less drecky work next time.

You can listen to the album here: