Album of the Week, April 26, 2025

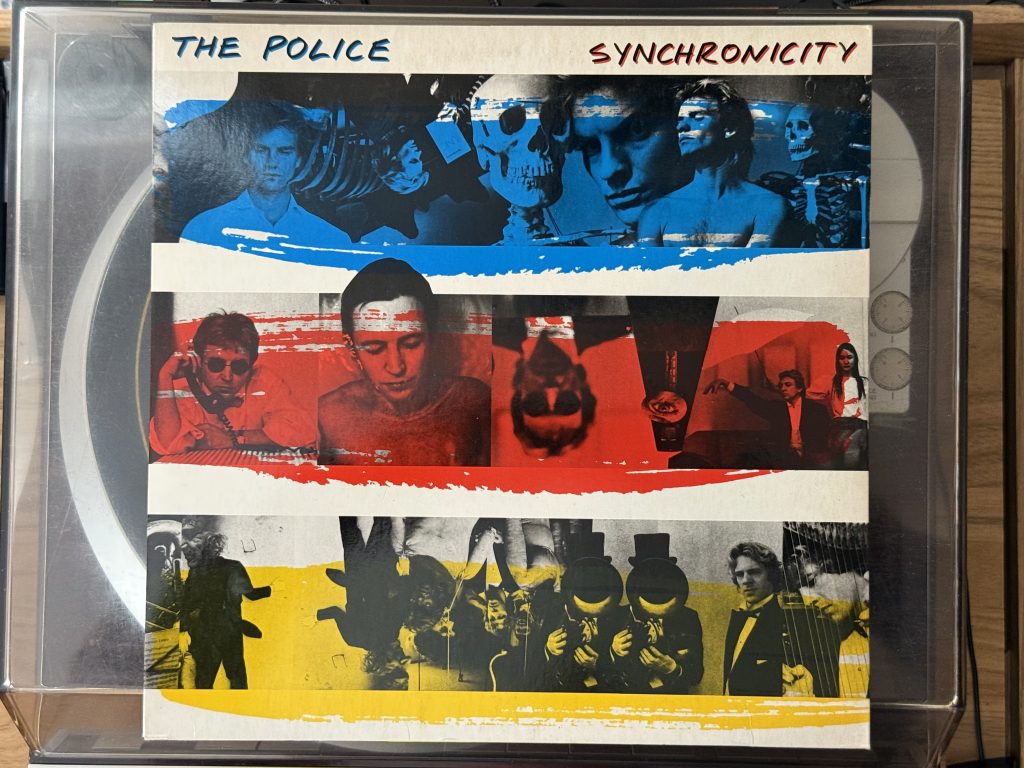

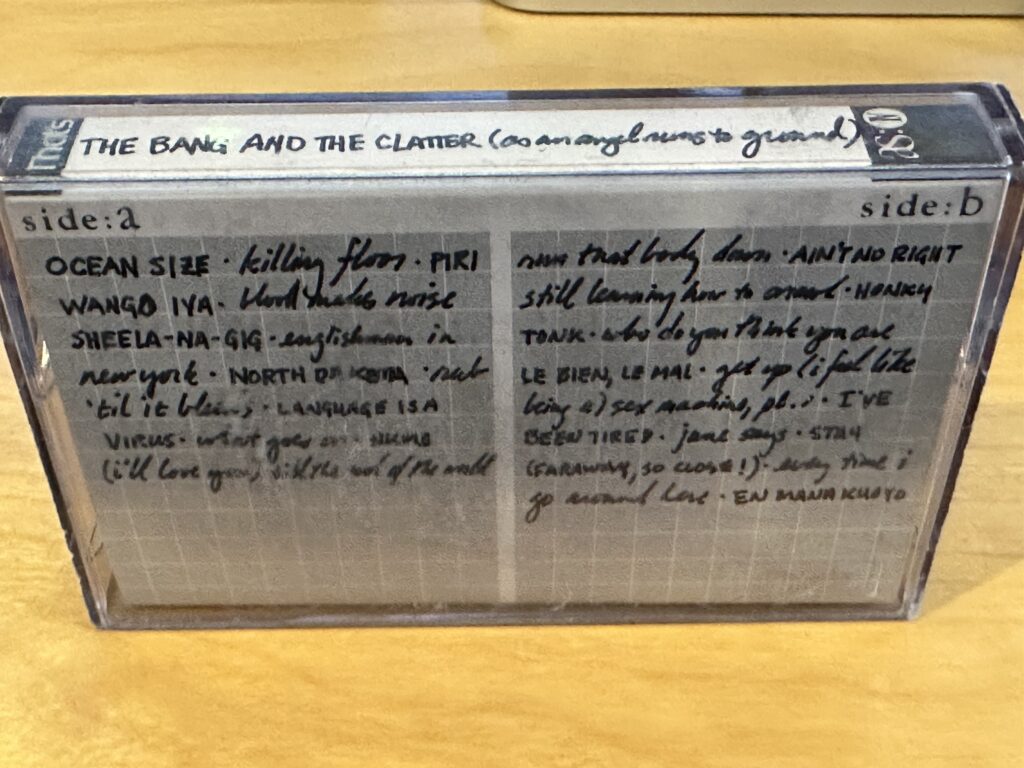

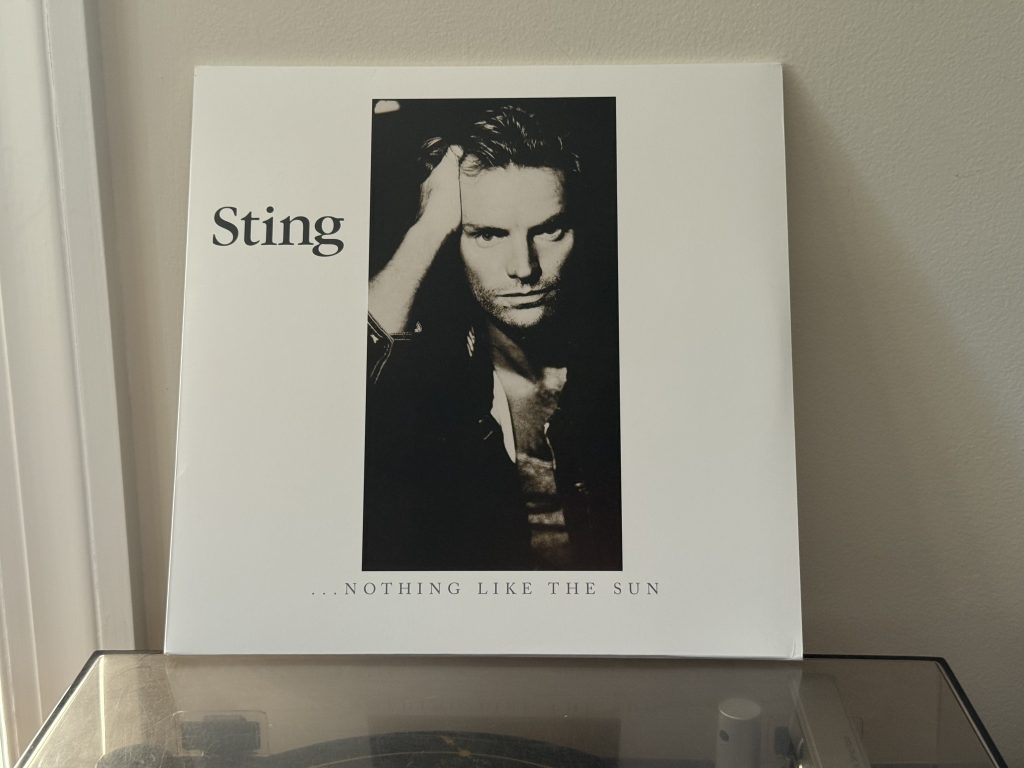

So it is that we come to Sting’s second solo album, and I have to warn you that I’m not sure I can be objective about this one. I was fourteen, almost fifteen when …Nothing Like the Sun, complete with its elliptical title, was released, and it pretty much consumed me. My parents gave me a copy on cassette; I joined a CD club, in part, to get a copy on CD. The tour was my first rock concert, at William and Mary Hall. For goodness’ sake, it was “Sister Moon” that got me attention from girls when I sang at a talent show at the Governor’s School for the Sciences in the summer of 1989.

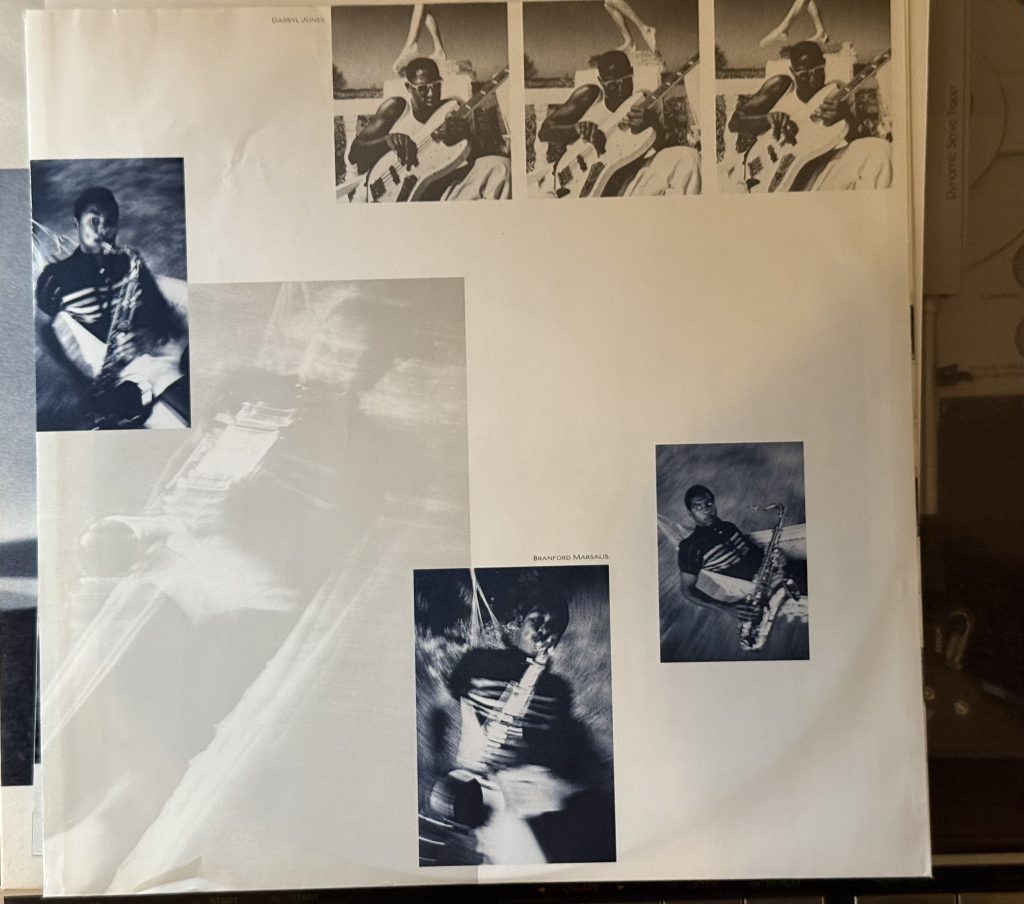

So let’s dive right in. “The Lazarus Heart” opens the album at full tilt and with seemingly every musician (as noted last week, both Omar Hakim and Darryl Jones did not return from Sting’s first solo album) making themselves known in the first couple of bars. There’s an arpeggiated guitar riff from none other than Andy Summers, over layers of more guitar and keyboards, percussion from Mino Cinelu and a bass pattern that seeks up to the supertonic. After four measures, Manu Katché’s snare and cymbals announce the start of the song. Branford and Kenny Kirkland play the opening hook together on soprano saxophone and a keyboard that sounds an awful lot like a flute. Sting’s vocals are syncopated and push and pull against the tempo as he tells the story of a dream of his mother and a wound in his heart. Even had Sting not dedicated the album to his mother’s memory, you would be able to tell that she loomed large in his subconscious still, seven years after he hurt both his parents with his words in a Rolling Stone interview. The arrangement itself feels dreamlike, with Andy Summers’ guitar and Kenny Kirkland’s keyboards echoing and washing around the corners of the song. There’s a brilliant moment at the bridge where Branford takes the tune out of the syncopated beat it’s been in since the start and pulls it into straight measure for about eight beats, and another in the last chorus where everyone but Mino Cinelu’s percussion drops out, revealing the richness of the arrangement by its absence.

Andy Summers sticks around for “Be Still My Beating Heart” (Sting asks in the liner notes, “Why does tradition locate our emotional center at the heart and not somewhere in the brain?”). This is a gentler song, but not a ballad, driven by a bass figure (doubled in the keyboards) that runs up from the dominant to the tonic, and washes of Andy Summers guitar that blend into saxophone obbligatos, all driven by the pulse of the percussionists. There’s subtle vocal harmony on the chorus and almost subliminal piano parts happening under the pre-chorus; the latter becomes apparent when the vocals drop out in the second chorus. The whole thing is the closest Sting ever got to writing a Sade song.

“Englishman In New York” stands as another in a long line of early Sting songs that are driven on the back of a busy synthesizer part, in this case a pizzicato string part that makes up the majority of the arrangement for the first verse of the song (turning into synth strings for the bridge). Thankfully there’s also a fantastic Branford Marsalis through-line on the soprano sax, as well as some top-notch contributions by Manu Katché (the hi-hat! the snare work on the first verse!) and Mino Cinelu (a fine use of the cuíca throughout the chorus). Branford gets a properly swinging solo verse after the bridge, with fine support from Kenny Kirkland. The whole thing was written as an homage to Quentin Crisp, as Sting reports in the liner notes.; there was a movie made of the gay icon’s last years in New York titled after the song, starring John Hurt.

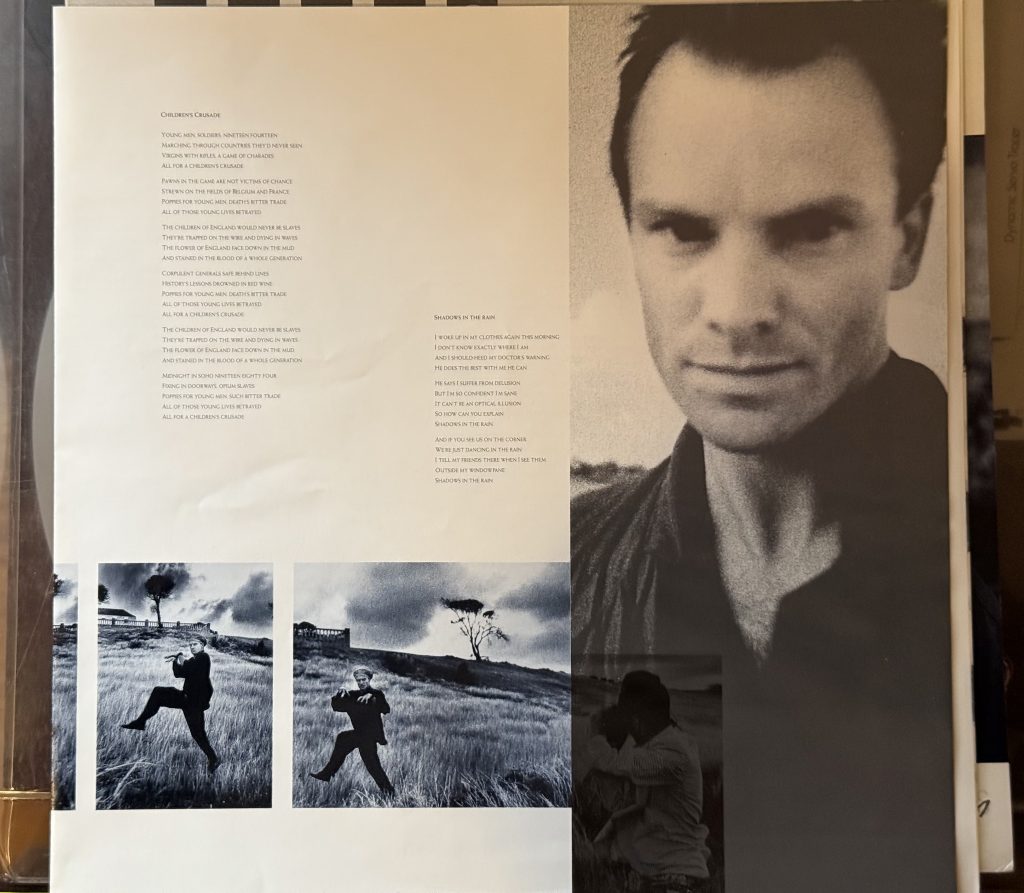

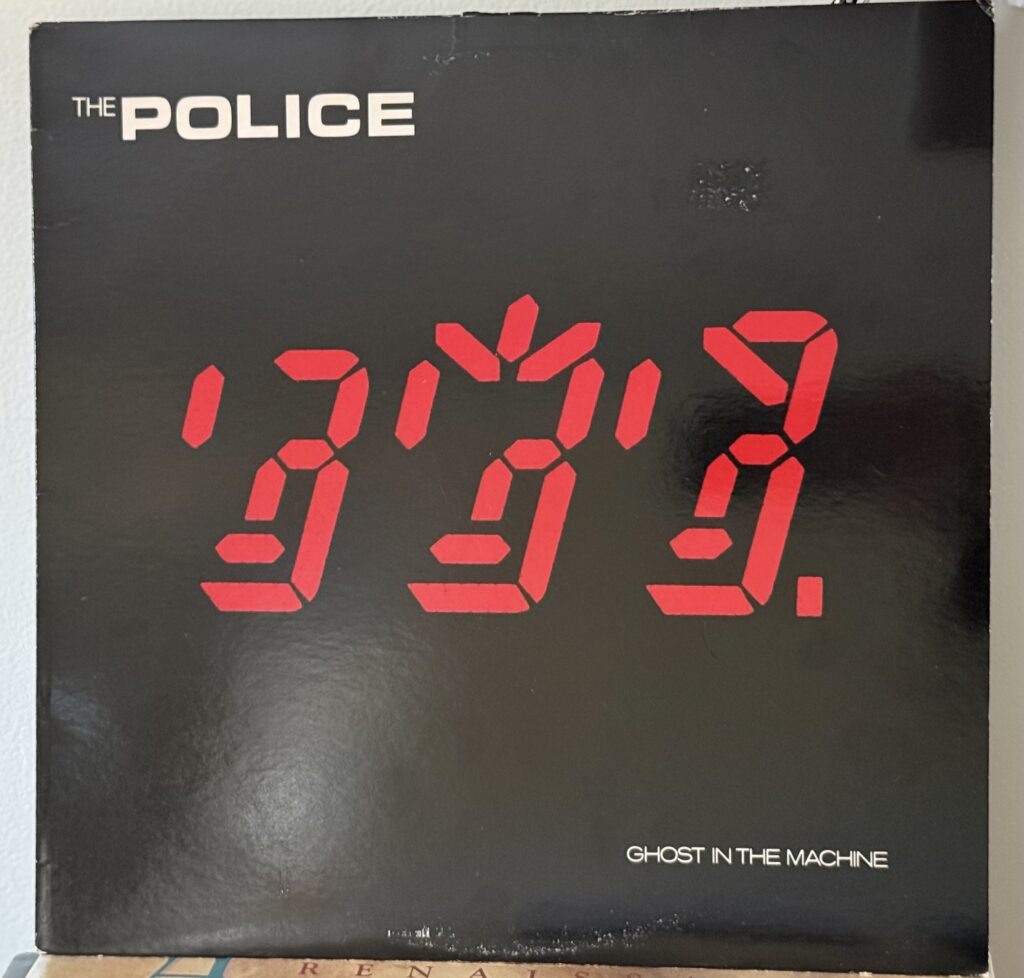

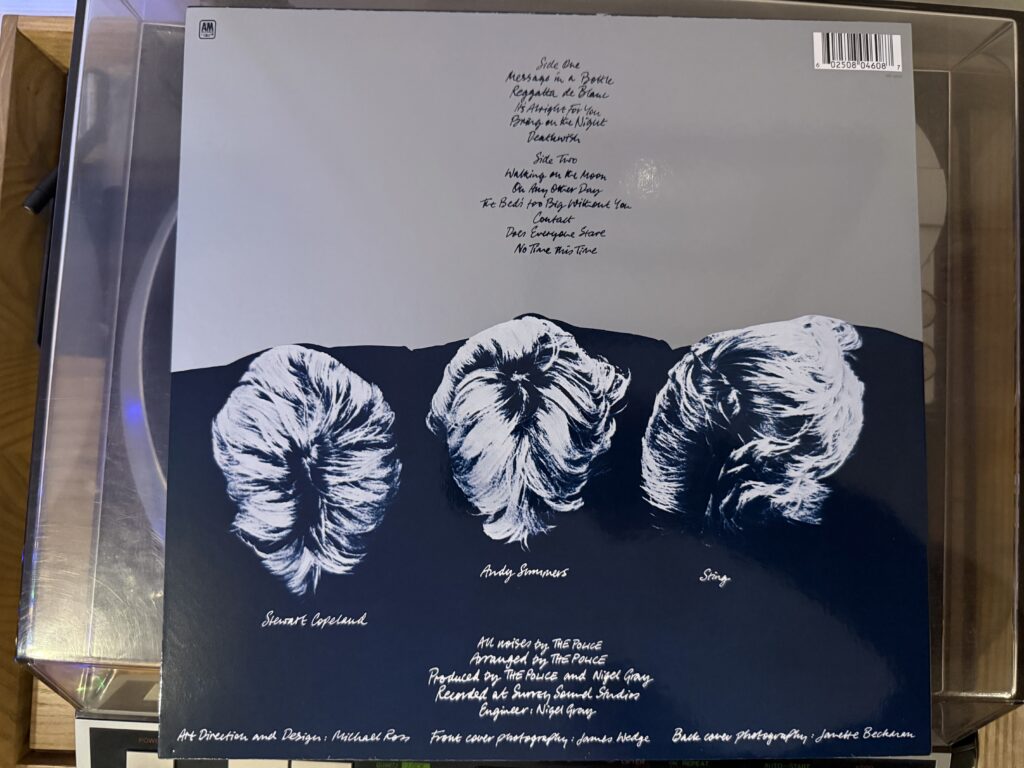

“History Will Teach Us Nothing” is the one reggae-inflected song on the album, Sting having mostly moved well beyond the days of Reggatta de Blanc by now. The groove, with guitar, bass, drums and percussion, is tight, but unfortunately the trick of doubling the sax with the keyboards seems to water down both here. Sting is in verbose mode, working on the theme of “Spirits in the Material World” and “Love is the Seventh Way,” calling for us to stop repeating history’s mistakes in the most provocative way possible—telling us to stop listening to it. Alas, we now know what happens when you ignore signs that history is repeating itself… I would say, though, that the outro chorus (“Know your human rights/be what you come here for”) is now perhaps more relevant than ever.

This takes us into the most topical song on the album, which I spent years thinking was on the wrong side of topicality until this year. Sting has talked about his writing process for the album following the death of his mother, as he retreated to an apartment in New York in a monastic existence; when he debuted this song and others to friends, they were powerfully moved but he didn’t feel it, having been locked inside his head for too long. “They Dance Alone (Cueca Solo)” is potentially a moving song, and certainly made more powerful by Sting’s focus on the “mothers of the disappeared,” who danced by themselves in anguished protest against the abductions and murders of their loved ones by the regime of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet. After years of performing in Amnesty benefits, he had fully inhabited the grief as well as the outrage of this cause. It’s unfortunate that this performance is the most adult contemporary of all the songs on the album; stretching to over seven minutes long, the song doesn’t even get Branford Marsalis until the last verse, and it wastes guest guitarists Eric Clapton, Fareed Haque, and Mark Knopfler, who seem to disappear into the texture of the song. I would totally write this one off, but for two things: the brilliant outro, when Kenny Kirkland finally can kick things into high gear by going into double time and Branford is let off the leash; and the fact that we now have more than enough opportunities to dance alone, without having to go to Chile.

“Fragile” ends this topical segment of the album with one of Sting’s finest ballads, written in memory of Ben Linder, an American civil engineer killed by the Nicaraguan contras in 1987 while he was working on a hydroelectric project. It succeeds where “They Dance Alone” fails by virtue of its brevity and restraint, with the majority of the song carried by the gentle percussion of Cinelu and Katché and by Sting’s remarkable Spanish-style guitar work. “Fragile” has been the touchstone to which Sting has returned in his career at times of national grief; it took on extra resonance as the lead-off song of All This Time, an acoustic set from his Tuscan villa that was recorded on September 11, 2001 as the musicians became aware of the facts of the attacks.

I wrote about “We’ll Be Together” last week at least in part so I wouldn’t have to this week. (There are a lot of songs on this album!) So let’s skip ahead. “Straight To My Heart” is another straight-up love song, and another one built on a programmed keyboard riff, but again it’s substantially improved by the percussion; here Katché and Cinelu play polyrhythms throughout, and the cuica makes another appearance. There’s another of those whistly synth lines throughout the chorus, but it works better here, and the whole thing has the feeling of a sonnet in 7/4. It’s a great band-kid song by virtue of the unusual meter; when I saw Sting live for the third time in Richmond in 1993 with my sister and her friends Jeremy and Christina, we made his band double-take as we bobbed our heads in perfect 7/4 time to this song.

“Rock Steady” is that rarity, a Sting song with a sense of humor. Despite the name, this is more a blues than a reggae number. As Sting retells the story of Noah’s Ark in a modern setting, we get imitations of the cries of the animals, whether by the sampler or by members of the band I’ve never quite been clear. Sting tells the story of two young lovers who get dragooned into helping Noah with the animals during the flood; once they’ve finally found dry land at the end and are leaving the boat, one of the backing vocalists (I’ve always imagined it’s Janice Pendarvis) teasingly asks, “Got any more bright ideas?” We don’t get too many laugh-out-loud moments in Sting’s oeuvre, so I take this one while I can.

“Sister Moon” is a saxophone feature and a dark ballad, in some ways reminiscent of “Moon Over Bourbon Street.” But where that song’s arrangement builds from acoustic bass to keyboard and saxophone, here the track builds on washes of synthesizer sound, with only Branford’s playing to break it up. Thankfully he gives a bravura performance. I somehow found a saxophone player at the Governor’s School for the Sciences at Virginia Tech in July of 1989 and he learned the part by ear. We performed it twice, and by the time we were done I had decided I wanted to sing for the rest of my life.

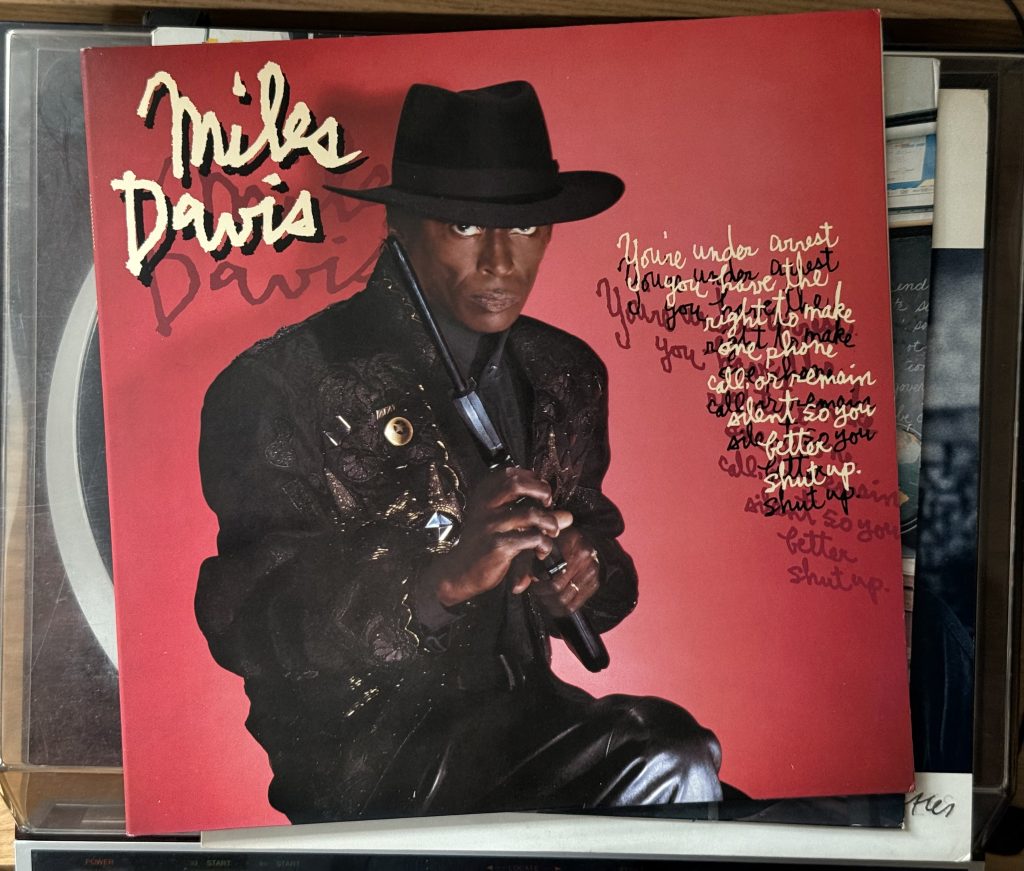

Ironically, “Little Wing” is the other song I’ve performed from this album, about 21 years and change ago. The arrangement on this album is pretty special, marking Sting’s first collaboration with the great Gil Evans, whom we last saw working with Miles Davis in Carnegie Hall, and whom I mentioned had cut a killer version of “Murder by Numbers” with Sting in the late 1980s. This is where that collaboration started, though apparently Sting had met him years previously at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club in London. The arrangement is an endorphin overload, with Evans’ orchestra and keyboards supporting Sting’s vocals as he sings the hell out of the Jimi Hendrix standard. Mostly what you hear, though, is Hiram Bullock’s guitar, which gets a great solo that transitions into a cool take from Branford before Sting recaps the verse once more at the end. (Bullock, who died in 2008, had played on a variety of rock and fusion recordings, including playing on Steely Dan’s “My Rival” from Gaucho and Paul Simon’s “That’s Why God Made the Movies” from One Trick Pony.)

On this album, “Little Wing” serves as the center of a three-song set about love, moving from the inchoate mooning of “Sister Moon” into a declaration of love that seems to combine muscular feats of strength with moments of heavenward striving. The last song on the album moves into something considerably more intimate. “The Secret Marriage” was written to a tune by blacklisted German composer Hanns Eisler, who partnered with Bertolt Brecht in both Weimar Germany and in the United States and who composed scores for some 40 films, before being run out of American on a rail by the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Sting performed one of the duo’s songs, “An Den Kleinen Radio-Apparat,” in 1987 and adapted the song’s melody for “The Secret Marriage.” It’s an intensely private statement of love, and is a striking note on which to end …Nothing Like the Sun, as if declaring an end to the rule of the King of Pain.

The album cycle for …Nothing Like the Sun, from its release through the tour and the eventual follow-up, lasted for almost four years. During that time a great many things changed, including the almost complete cessation of new music releases on vinyl in the United States. You can find a copy of the follow-up, The Soul Cages, on LP but you have to really look hard, and the subsequent albums weren’t released in vinyl form in the US, or at all. (There’s still no US release of Ten Summoner’s Tales on vinyl, to my surprise.) Sting also played less jazz following the completion of this song cycle; though Kenny Kirkland played on The Soul Cages and Branford guested on a few songs, for the most part Sting has stayed straight on in the pop lane ever since. But Branford’s career as a bandleader was just taking off; we’ll hear one of his quartet’s albums next time.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

BONUS: There were some really interesting b-sides from this album. Last week we heard “Conversation with a Dog,” but there was also the jazz piece “Ghost in the Strand,” a pop song that maybe should have made the album (“If You There”), Sting’s well-done cover of Gershwin’s “Someone to Watch Over Me,” and an adventurous collaboration with Gil Evans on Jimi Hendrix’s “Up From the Skies.” (I wrote about getting “Someone to Watch Over Me” and “Up From the Skies” off a 3-inch CD single, with some difficulty and an adapter, some time ago.) The last spawned a full concert collaboration between Sting and the septuagenarian arranger/bandleader at the Umbria Jazz Festival in Perugia, Italy in 1987; you can watch that widely bootlegged performance below:

BONUS BONUS: There’s a popular but as far as I can tell apocryphal story that the song “The Lazarus Heart” was written for the movie Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, to be played over a scene that would have come from the original novel in which Roger is killed at the end of the movie. Sad to say, there is no footage combining the two.