Album of the Week, August 10, 2024

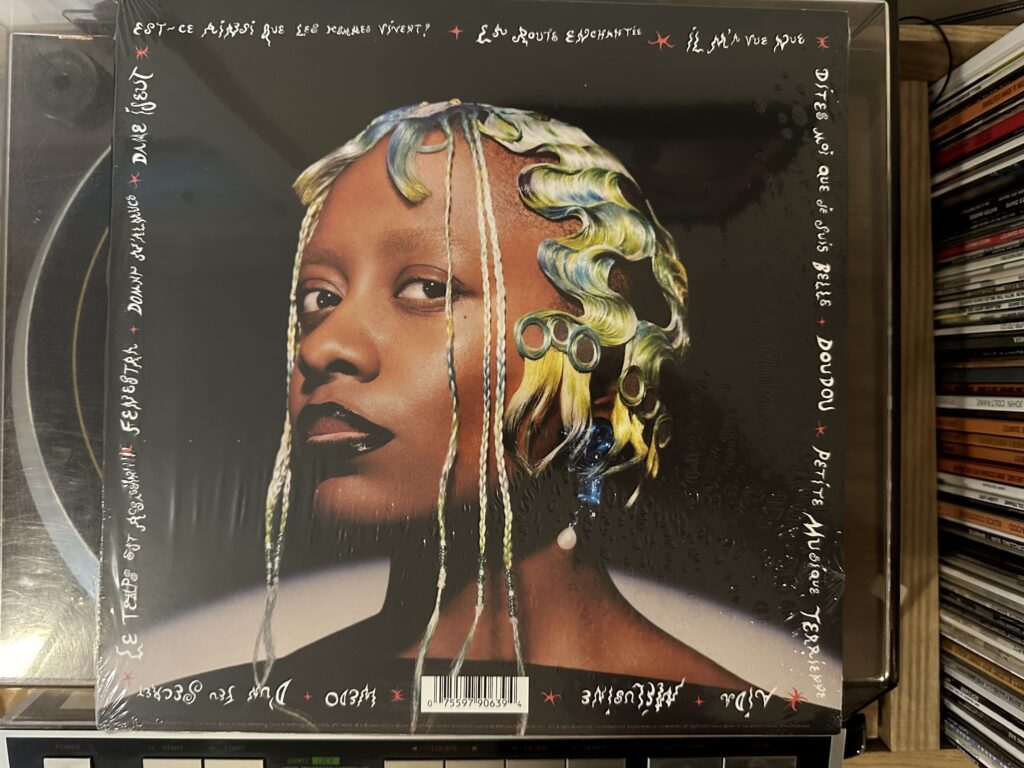

If you’re going to listen to Cécile McLorin Salvant, and (as you can tell following my reviews of Ghost Song and her earlier albums) I highly recommend it, and you don’t speak French, you have to decide how to approach an album like Mélusine, which is entirely sung in French except for one song in English, another in Occitan (aka Provençal), and some in Haitian Kreyol. My recommendation: just listen. Her phrasing is impeccable; her vocal technique flawless, and she can catch you unawares in French just as she does in English. And then, after you’ve listened, find a good translation of the lyrics, and fall down the rabbit hole.

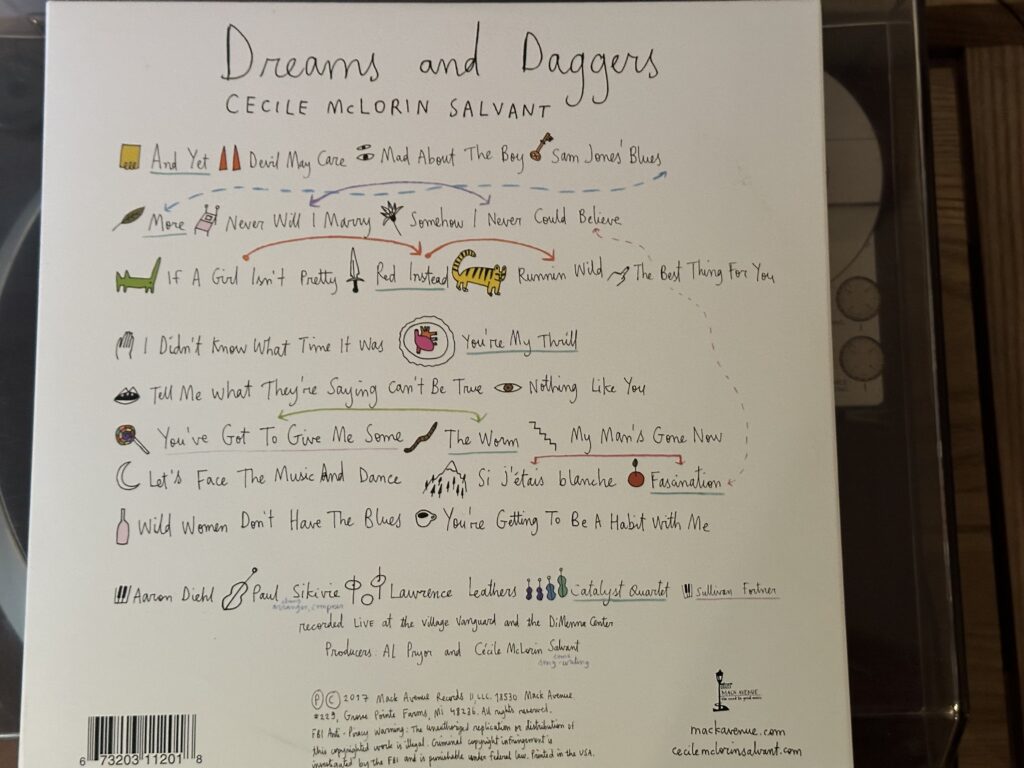

Mélusine refers to the legend of a woman cursed by her mother to turn into a half snake every Saturday, and the man who, distrusting her request for privacy on her reptile days, batters down the door only to see her become a dragon and fly away. As a metaphor—for the life of an immigrant, for the bitter failure of men and women to create authentic trust —it’s a rich one. This album, with its DNA half in jazz, half in French chanteuserie, seems another example of the metaphor. Also the personnel; the album opens with a pair straight ahead trio tracks with her first trio (Aaron Diehl, Paul Sikivie, and even an appearance by the late Lawrence Leathers on drums alongside Kyle Poole), and continues into more adventurous fare with Sullivan Fortner on piano and a seemingly never-ending set of combinations of Weedie Braimah on percussion, Luques Curtis on bass, Obed Calvaire on drums, Godwin Louis on alto sax and whistle, and Daniel Swenberg on guitar.

The album accordingly ranges across different moods and styles. “Est-Ce Ainsi Que Les Hommes Vivent?,” made famous by Yves Montand, here aches with despair but is given its heart by Cécile’s amazing voice, particularly in the chorus when her tone becomes pure and true. Aaron Diehl’s piano is similarly miraculous ranging from a rocking rhythm to twinkling stars to discordant bells within a few short moments. The band is similarly fluent on “La Route Enchantée,” bringing a subtle rhythm and a not-so-subtle joy to the Charles Trenet song.

Things go further afield on “Il M’a Vue Nue,” literally “he saw me all nude.” The song is given a jaunty cheerfulness by the whistling opening and winking narration, as well as the interchange between the rock solid drums and gently syncopated piano. “Dites Moi Que Je Suis Belle” shifts gears into a more percussive world; accompanied only by Weedie Braimah’s precise djembe, Salvant interprets the Yvette Guibert adaptation of Jules Massenet’s lyric from Thaïs with a kind of yearning demand: “tell me I am beautiful! Say I shall be lovely until the end of time!”

“Doudou,” a Salvant original, carries more than a hint of the Afro-Latin about it and is enlivened by both Godwin Louis’s saxophone and the New Orleans flavored percussion. Salvant has been performing this since 2017 when she premiered it with Wynton Marsalis at Marciac, and there are clearly elements of the original arrangement at play here, but it has an element of lightness and playfulness in this reading, especially in the stacked harmony vocals and seamless shift into a slow four in the last chorus.

With “Petite Musique Terrienne,” originally performed by Fabienne Thibeault, we are alone with Salvant and Fortner, even as the former stacks harmonies on the chorus, joined by a synthesizer line from Fortner on the final “Who will tell us what we’re doing here/In this world that doesn’t look like us?” “Aida” has a similar construction on even slighter lyrics, and here it’s all Cécile on both vocals and keys.

Both songs serve as a kind of prelude to “Mélusine.” We’re in English, but we aren’t in a straightforward narrative. Are we the woman, forever turning into a half-snake in her Saturday bath? Are we the wondering, distrustful lover? The classical guitar doesn’t tell us; the retelling of the Mélusine story in French in the last verse only adds to the mystery of the two worlds colliding.

“Wedo” is all Cécile again, the beat of a children’s song telling the very unchildish Voudoun tale of Ayida-Wedo, the half-male, half-female serpent that with her husband Damballa crossed from Africa to Haiti to bring the religion of the loa to the new world. The song rings out like an echo of “Mélusine,” telling the same story in a different time and language. “D’un feu secret” gives us Cécile in her purest tones, untouched by nasalized French vowels, even as Fortner’s synthesizer brings its squelchiest tones. The secret of Mélusine, she sings, is unknowable: “When we know… it will be well known that I have ceased to live.”

“Le temps est assassin,” originally performed by Véronique Sanson, is performed as a straightforward ballad singing an unstraightforward lyric: “Sometimes I feel the mysteries of all these things I can’t get my head around… I say that time is an assassin, and I don’t want anything anymore.” The death of desire and the duality of Mélusine and Aida Wedo flying—out the window, from Africa to Haiti—entwine together in “Fenestra,” which returns to the gently calypso-flavored rhythms of “Doudou,” finally begins to dig into the mysteries: “As for the women who seduced their angels, they will become sirens.” And the different strands of the record entwine into a single syncretic whole as we embrace the rhythm, the brilliant piano, the Haitian folk tales, the older European legends, all together given voice by Salvant.

The ending gives us a pair of mysteries: “Domna N’almucs,” originally by Iseut Da Capio, the voices of two Occitan noblewomen in dialog from medieval times (a scholarly paper talks about the substance of the exchange, with one woman asking the other to forgive her lover), accompanied by a subtle wash of synthesizers. And “Dame Iseut” returns us once more to the islands for a brief epilogue in Haitian Kreyol.

Cécile McLorin Salvant, at the beginning of her career, told stories through song. Now, after Grammy awards and a Genius Grant, she takes us on journeys across musical styles, time and space, personal and mythic, all in that magnificent voice. I’m looking forward to the next one when it comes out. But next week we’ll close out (for now) this series on jazz vocalists with one more from Kurt Elling.

You can listen to this week’s album here: