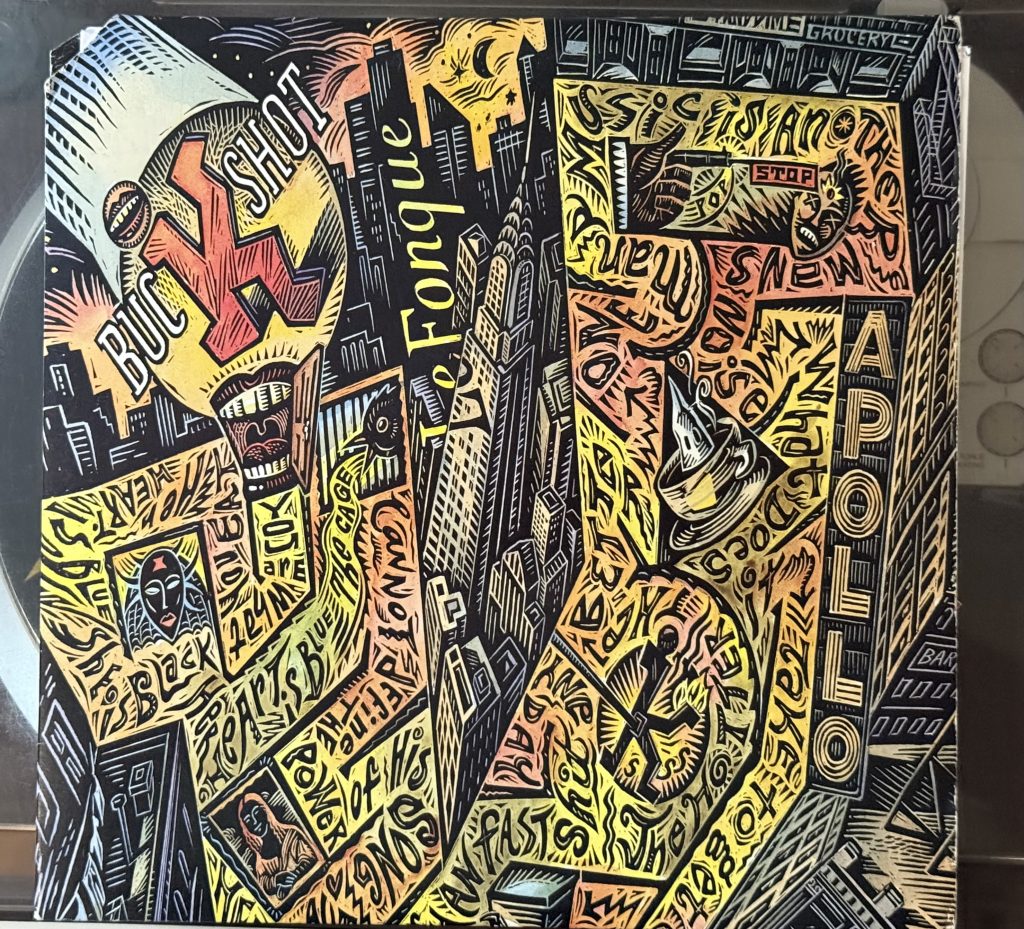

Album of the Week, June 28, 2025

I started off my review of Branford Marsalis’ The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born with the observation that Branford effectively was managing two brands by the time the early 1990s rolled around. There was Serious Jazz Branford, which that record represented very effectively. And there was Crossover Branford, who played with Sting and the Grateful Dead and collaborated with hip-hop artists on the soundtracks to Do the Right Thing and Mo’ Better Blues—and, by 1992, was the new music director of the Tonight Show with Jay Leno.

The thing about having two brands, as any marketing expert will tell you, is that at some point it gets confusing. It’s great if a follower of your one brand will branch out and try your other, but more often than not it just leads to confusion and disappointment. The trick is to go all the way and embrace the new brand completely, including a new name. I don’t know for sure if that’s why Branford embraced the name Buckshot Lefonque for his new crossover hip-hop/R&B band endeavor, but it seems likely. It also helps that the name was just sitting there; Cannonball Adderley called himself “Buckshot La Funke” for contractual reasons on a 1958 Louis Smith session.

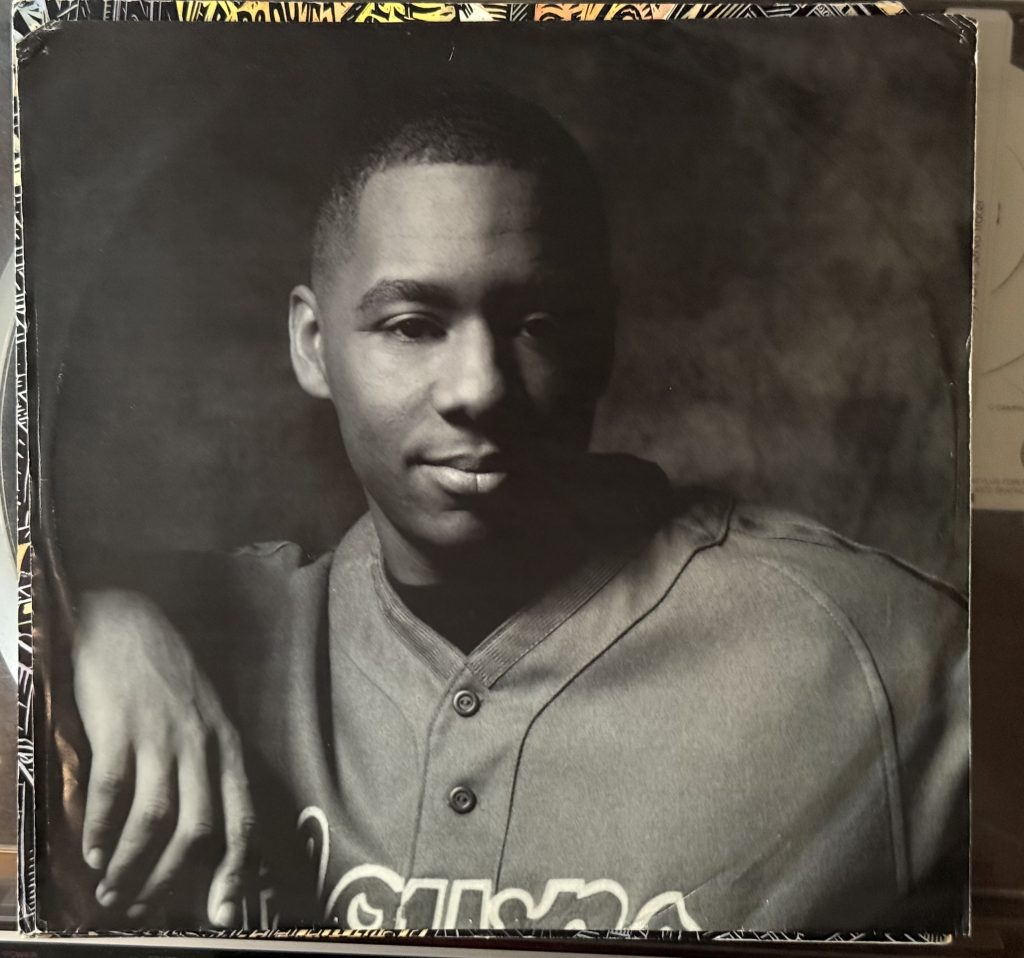

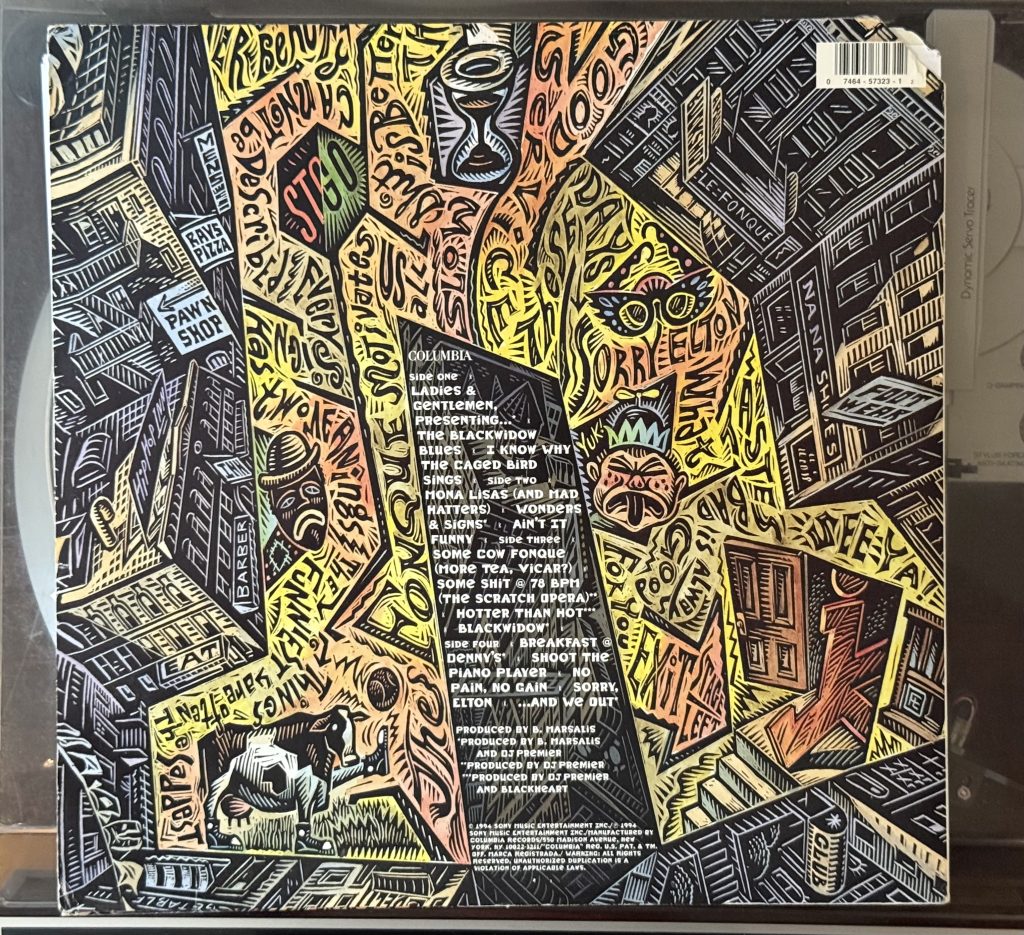

There’s a lot of musicians on this one, including stalwart bandmates Kenny Kirkland, Robert Hurst and Jeff “Tain” Watts, but there are some new faces too. Roy Hargrove, who died at the age of 49 in 2018, is here on trumpet, and Delfeayo Marsalis on trombone. Guitarist Kevin Eubanks, who played in the Tonight Show band with Branford (and later became its director), is here. But the main collaborator is DJ Premier, who was Guru’s partner in the pioneering jazz-inflected hip-hop combo Gangstarr. The hip-hop duo was one of a small crowd that mixed jazz samples with rapping and turntables in the late 1980s and early 1990s; I put together a mix from this period a little while ago.

The album takes no prisoners, dropping you directly into the scratch and sample filled “Ladies and Gentlemen, Presenting…” It’s a stage setter akin to the opening of Us3’s Hand on the Torch, in which chopped up dialog samples play over a horn vamp from Branford and Roy Hargrove. It leads directly into the “Blackwidow Blues,” a far more ambitious production that starts with a keyboard track from Kenny Kirkland and then drops in the first significant sample, an Elvin Jones drum and cymbal beat from John Coltrane’s “India.” Branford does some drum programming on top of this loop, and the band as a whole plays a sinuous melody that sets up a Branford tenor followed by a meaty trombone solo (both Matt Finders and Branford’s brother Delfeayo are credited on trombone here). Roy Hargrove, playing the Freddie Hubbard part in this stew, gives a fine, high trumpet solo and then passes the ball to Branford for another go. The blues swings hard right up through Kenny’s electric piano solo. This is jazz filtered through a hip-hop sensibility, not the other way around, and it’s a rich listen.

The single most memorable track on the album comes early. “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” is built around a sample of birdsong and around author Maya Angelou’s reading of her poem, and two samples, from Ruben Blades’ “Prohibido Olvidar” and Fela Kuti’s “Beasts of No Nation.” But the groove, and the tasty duet between Branford and Hargrove, allows us to be blissfully ignorant of the bones on which everything rides. There are four guitarists credited on the track, including Branford’s successor on the Leno Show Kevin Eubanks and genius Nils Lofgren, but they blend seamlessly into each other. Mino Cinelu’s percussion sits at the bottom along with Kenny’s piano, keeping everything together.

“Mona Lisas and Mad Hatters” is an adaptation of the Elton John/Bernie Taupin and is performed as a more straight ahead R&B track, albeit with some interesting touches like Amharic vocals in the opening. But the beat, driven by Cinelu’s percussion and none other than Jeff “Tain” Watts’ mighty snare, provides more traditional accompaniment to vocalist Frank McComb. The last chorus, which combines some compelling vocal licks from McComb atop some equally tasty keyboard work from Kenny Kirkland, is the best part.

“Wonders and Signs” is built around a reggae vocal from Blackheart, and pulls together most of the band, including Branford, Hargrove, Kenny, Cinelu, and fellow Sting band alum Darryl Jones for a dub-inflected improv atop the “Introducing” vamp. If you don’t enjoy extended passages of toasting in a thick patois, this one is probably not for you, but there’s still some worthwhile listening in the form of Roy Hargrove’s angular trumpet solo atop David Barry’s guitar, and the flurrying Branford soprano solo atop the sung final chorus.

“Ain’t It Funny” is another more traditional R&B track, with strings (arranged by Clare Fischer) providing the bed for Tammy Townsend’s vocals. While I was prepared to dislike this thanks to the clumsy marriage of song and band on the lead-off track on Branford’s Mo’ Better Blues soundtrack, this one is far more successful; if it had played on R&B radio circa 1985-1986, I think it would have been a hit in its own right. There are, unusually, no horns on the track, but that’s Kenny Kirkland on the keyboards and Kevin Eubanks laying down the guitar solo in the outro.

“Some Cow Fonque (More Tea, Vicar?)” is another number that leans hard into the alchemy between DJ Premier’s sampling and the full band, atop a vaguely country-meets-Delta-Blues soundscape thanks to Kevin Eubanks’ slide guitar work. The horn charts are thick, with Chuck Findley’s trumpet and Matt Finders’ trombone joining Branford and Hargrove, along with both Robert Hurst and Darryl Jones on acoustic and electric bass and Tain on drums. It’s a romp.

“Some Shit @ 78BPM (The Scratch Opera)” is a DJ Premier showcase, and how much you like it will entirely depend on whether you find scratching enjoyable or annoying. It’s OK once the beat drops, but the horn sample that he chose as the backbone of the track doesn’t seem to entirely know what key it’s in. I covet the vocal samples that he uses throughout here, though, especially “We have reached our rendezvous… with destiny!” And Branford’s sax on top is quite good.

“Hotter Than Hot” brings Blackheart back for a faster paced reggae number. It’s a sparer track, with a little bit of Branford, drum and cymbals, and bass left to back up rapid-fire patois. The riddim is toasty, but I’d love some deeper bass here. Branford’s solo, including overdubs, is worth a listen.

“Blackwidow” (also called “Blackwidow Blues” on the streaming services and reprising the “India” sample with heavy scratching) is introduced by a sample of a Jay Leno monologue in which he calls out a now-all-but-forgotten incident when six African-American Secret Service agents, guarding President Clinton, were refused service at a Denny’s in Maryland. (Tl;dr: they sued, it became a class action suit, they won.) The track plays like the dub cousin of the opening “Blackwidow Blues,” with a heavy Robert Hurst bass line helping to anchor the horns. We get extended horn solos — 32 bars rather than 16 — which are further extended by sampling and scratching. The spoken word sample, in which a white announcer exclaims “I’d like to have the pleasure of introducing the greatest living master of jungle music,” underpins the harder edge to the track, but Branford reclaims the narrative with a fiercely overblown tenor solo.

“Breakfast @ Denny’s” adds a James Brown sample to the basic “Blackwidow” track, but most of the story here is the tight, angry rap from little-known emcee Uptown, who spits bars about discrimination: “Imagine being hungry and man you want to eat/You go inside the restaurant and can’t get a seat.” In this context, Branford’s tight solo reads less like a party and more like a challenge.

There’s a link, “Shoot the Piano Player,” with “sad assed piano” courtesy of Delfeayo, leading into “No Pain, No Gain.” The song builds around a sample from Bela Fleck’s “Sex in a Pan” and settles into a vicious Victor Wooten bass line, guitar from blues legend Albert Collins, and vocals from Uptown, leaving an overall impression of Living Colour or even Rage Against the Machine. It’s the hardest rocking track on the album and makes me wonder what a Branford/Rage collab would have sounded like.

We return to the “sad assed piano player” for “Sorry, Elton,” where we actually get the promised shot and the sound of the piano player collapsing against the keys, leading into “And We Out.” The last track on the LP reprises the “Presenting…” theme with a sort of party ambience, minus the vocal samples. We began in a sampling playground, but we end with something more real and organic, especially with Matt Finders’ trombone solo bumping right into David Barry’s guitar. It’s a party I’d like to be at.

Branford’s pop-star brand wasn’t destined to last forever. He got more serious about the jazz side of his career in the late 1990s, especially after the unexpected 1998 death of Kenny Kirkland. There was one more Buckshot Lefonque album and a few more pop credits, but he’s largely been a serious jazz artist since then. This year’s Blue Note Records debut, an album-long cover of Keith Jarrett’s Belonging, is an outstanding example of his craft, and there have also been great collaborations with Kurt Elling and others along the way. He seems to have many more vital years in him.

Next week we’ll shift gears and pick up a thread I’ve left dangling for quite a while, about a pianist and a composer who was, as the great saxophonist Charles Lloyd once observed, “not exactly linear.” Stay tuned.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

BONUS: There was actually a music video for “Breakfast @ Denny’s” — minus the Uptown rap, and with the Jay Leno monologue joke layered over the top. The video is eloquent even without the narrative.

BONUS BONUS: Buckshot LeFonque did some media behind the original album. Here’s “Some Cow Fonque” live from the Conan O’Brien show! The band for this one doesn’t have a lot of overlap with the players on the record, but that’s Mino Cinelu on percussion, and one of the two keyboard players is none other than Joey Calderazzo, who went on to fill the piano seat in the Branford Marsalis Quartet after Kenny Kirkland’s death and has held it for over twenty years.