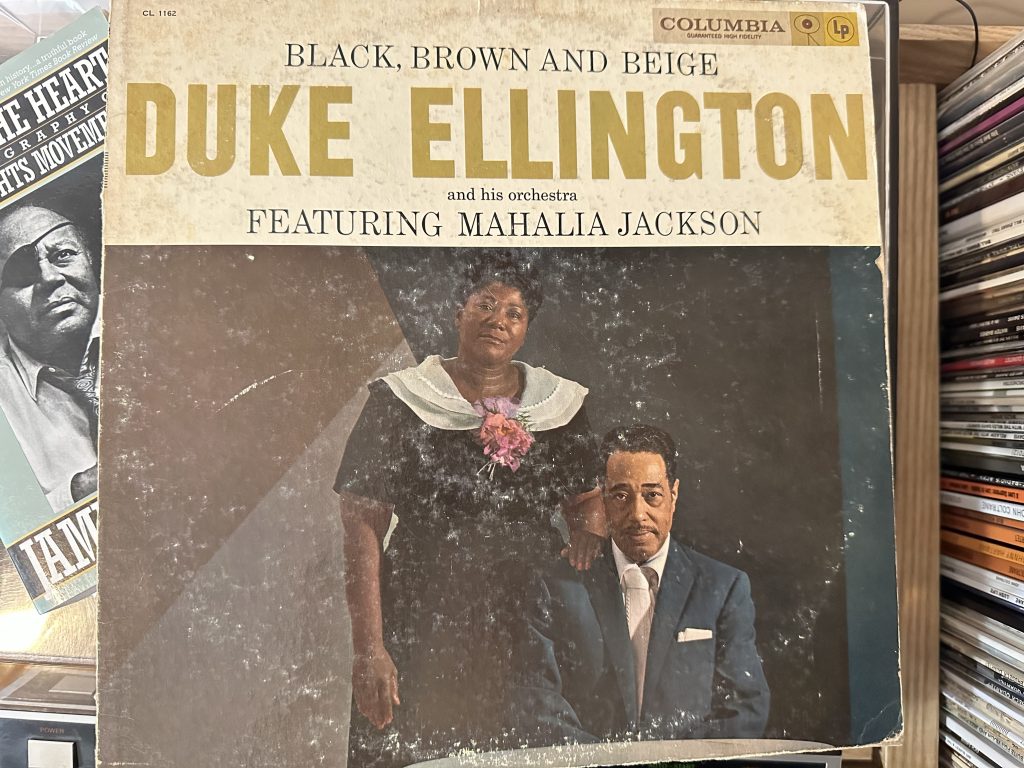

Black, Brown and Beige (1958) by Duke Ellington and His Orchestra Featuring Mahalia Jackson.

Album of the Week, November 5, 2022

We rejoin Duke Ellington in 1958, and much has changed from the 1951 release of Masterpieces by Ellington. Following the long-form recording breakthroughs of that album, Duke dove into avant garde compositional forms (Uptown), re-recordings of his own music as solo piano arrangements (The Duke Plays Ellington, later reissued as Piano Reflections), and relative obscurity. At this point in his career, his main income was compositional royalties, and he didn’t have a record deal. He is said to have booked his band into ice skating rinks so that he could keep them busy enough to pay them.

Then came the band’s 1956 performance at the Newport Jazz Festival, captured in the famous Ellington at Newport recording, and suddenly Ellington was hot again. I won’t be writing about that album at length (at least not right now), as I don’t have a vinyl copy, but it utterly jump-started his career, leading to a recording contract with Columbia Records. Columbia lost no time in capitalizing on his new popularity, and a series of recordings followed that mark some of the high points of the Duke’s output. One of them was Black, Brown and Beige, which revisited a work that Ellington had composed in 1943 for his first-ever appearance at Carnegie Hall.

Leonard Feather’s notes for the original suite describe a hugely ambitious work: “Black, the first movement, is divided into three parts: the Work Song; the spiritual Come Sunday; and Light. Brown also has three parts: West Indian Influence (or West Indian Dance); Emancipation Celebration (reworked as Lighter Attitude); and The Blues. Beige depicts ‘the Afro-American of the 1920s, 30s and World War II’.” The original performance received a lukewarm reaction, with critics objecting to the attempt to blend jazz and classical music. But when Ellington revised the suite in 1958, these objections were largely by the wayside, as the growing “third stream” movement had opened the door for jazz to cross over into other genres.

Still, Ellington did simplify the concept of the suite even as he expanded it. The 1958 revision essentially stripped the suite back to focus primarily on the themes from Black, “Work Song” and “Come Sunday.” In doing so, the suite becomes a meditation on the contrast of the African-American slave experience and the the Church, a point underscored by the groundbreaking inclusion of Mahalia Jackson as the vocalist.

It’s tempting to skip directly to “Come Sunday” in reviewing the album, but the degree to which “Work Song” shapes the suite and lays out Duke’s narrative intention should not be overlooked. The opening pounding drums of Part I are all that remain of the original narrative opening of the suite, and a peek at the score here is revelatory. The opening notes state:

A message is shot through the jungle by drums.

Ellington, opening notes to Black, Brown and Beige

BOOM! BOOM! BOOM! BOOM!

Like a tom-tom in steady precision.

Like the slapping of bare black feet across the desert wastes.

Like hunger pains.

Like lash after lash as they crash and they curl and they cut. DEEP!

Ellington was firmly grounding “Work Song” in the context of dislocation and enslaved labor, and returns to this theme over and over to emphasize this opening fact of African-American history.

In this context, “Come Sunday” comes as an almost revolutionary statement of hope. In the first statement, in Part II of the suite, the theme is played by the band, with an interpolation of “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” by the trombones making explicit the connection to African-American spirituals. And it is visited by all the members of the orchestra in turn going into Part III, alternating with “Work Song,” as the first half of the album ends.

“Part IV”, opening the second side of the record, begins with just Ellington and Mahalia Jackson. At this point we should acknowledge how groundbreaking this moment was. Gospel singers didn’t cross over to other musical forms, at least not still remaining gospel singers. There were plenty who left the form, Sam Cooke and some of the other early soul singers among them, but for Mahalia Jackson, at this point indisputably the greatest living gospel artist, to collaborate with Ellington on this record was unprecedented. One suspects that producer Irving Townshend, who also had produced Jackson since her Columbia debut in 1955, had something to do with it.

Whatever the origin, this recording, and “Part IV,” mark the debut of Ellington’s lyrics for “Come Sunday.” And some lyrics they are. They are essentially a gospel statement of faith in the face of racial oppression:

Lord, dear Lord I've loved, God almighty God of love, please look down and see my people through I believe that sun and moon up in the sky When the day is gray I know it, clouds passing by He'll give peace and comfort To every troubled mind Come Sunday, oh come Sunday That's the day Often we feel weary But he knows our every care Go to him in secret He will hear your every prayer

After a reprise of the “Come Sunday” theme by Ray Nance’s violin (Part V), the suite concludes with Jackson’s improvised rendition of Psalm 23 in Part VI. The liner notes claim “on the last afternoon, Duke asked Mahalia to bring her Bible with her. He opened it to the Twenty-Third Psalm, played a chord, and asked her to sing.” The presence of orchestra accompaniment on this track suggest that the degree of improvisation in the final movement may be overstated here; still it’s a stunning vocal performance.

Ellington recorded the work on four days from February 4 to February 12, 1958. Six months before, the Little Rock Nine had entered Little Rock Central High School for the first time, and five months later, the first sit-ins were held at Dockum Drug Store in Wichita, Kansas. It’s tempting to just hear this iteration of Black, Brown and Beige as a gospel meets jazz performance, but the full story places it solidly as a statement of solidarity with the Civil Rights movement and an important precursor to more explicit Civil Rights themed jazz suites like Sonny Rollins’ “Freedom Suite” (June 1958) and Max Roach’s “We Insist! Freedom Now” (1960).

You can listen to the album here: