Album of the Week, February 22, 2025

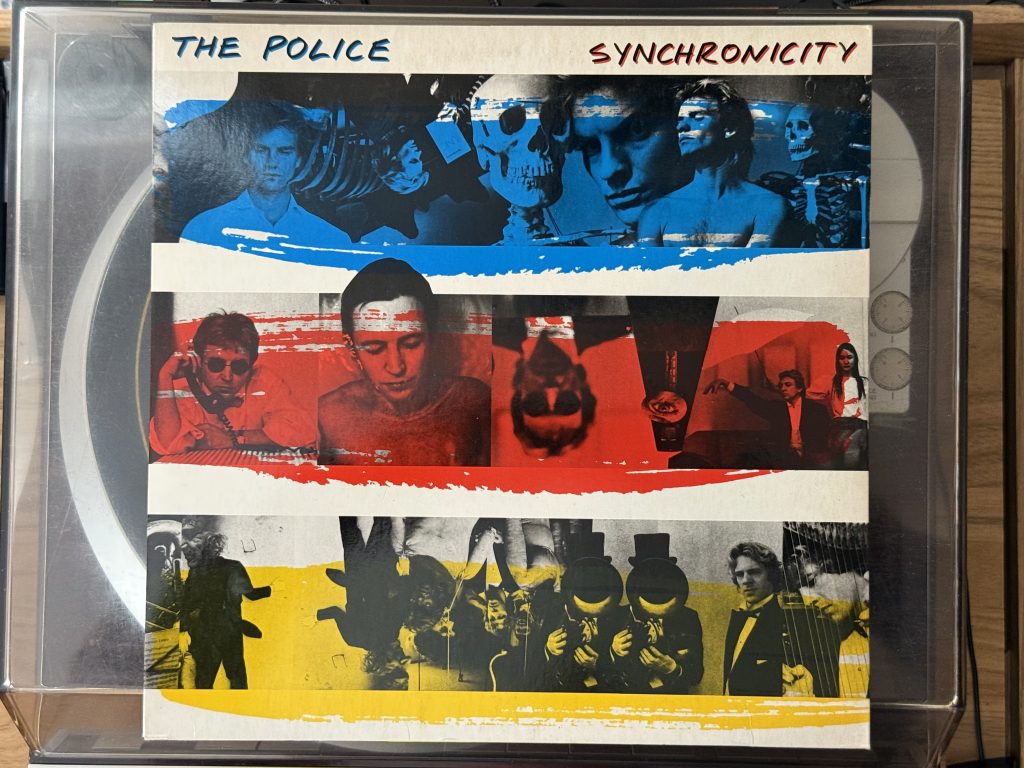

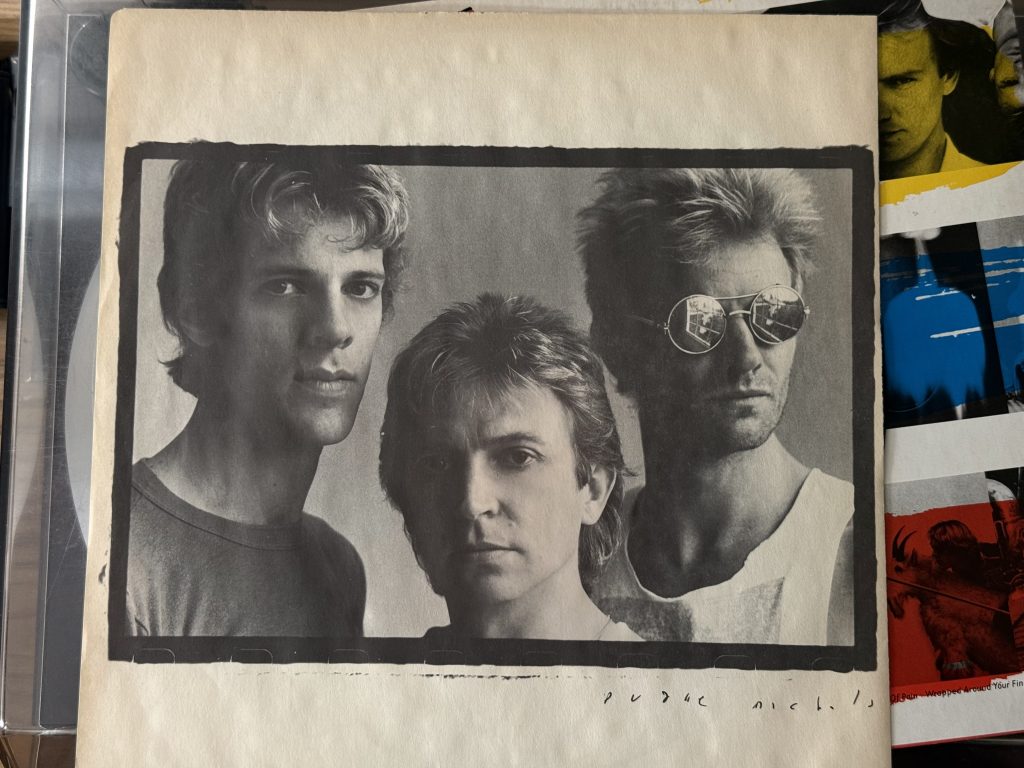

All good things come to an end, especially when the things that make them great are also tearing them apart. The creative tension between Sting’s pop instincts, Stewart Copeland’s intense rhythmic drive and post-punk brilliance, and Andy Summers’ guitar skills had combined in a heady brew over four LPs, many b-sides, and a soundtrack. Now they were in the studio one last time, and at each others’ throats.

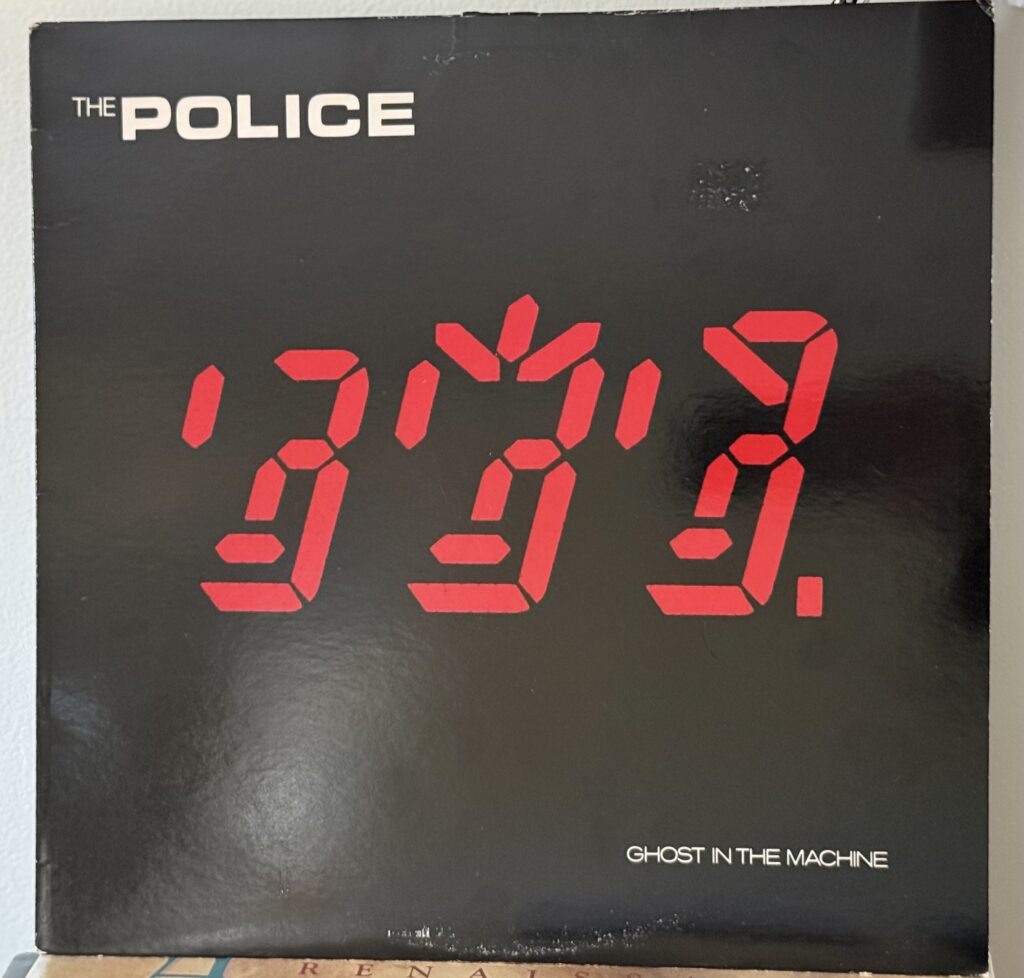

Maybe not constantly at each others’ throats. You have to be in the same room to have a physical fight, and for most of the recording of Synchronicity the band was not. Back at AIR Studios in Montserrat where they had recorded Ghost in the Machine, the band was spread across the residential studio: Stewart Copeland and his drums were in the dining room, Sting was in the control room with his bass, and Andy was in the actual studio. Hugh Padgham, back behind the console, did this both to get the best sound out of each instrument and “for social reasons.”

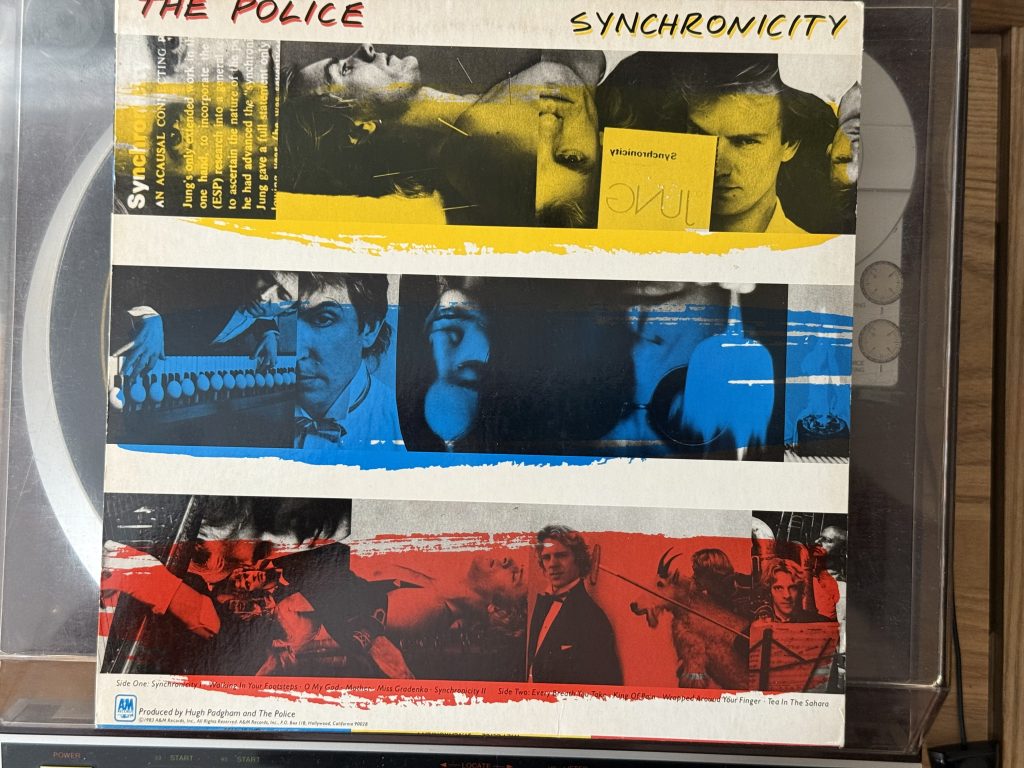

Tensions were high because the band was pulling in two different directions. Sting had come in with songs in a very pop direction that left most of the reggae influences behind; Stewart and Andy still wanted to have a go at creating the songs as a collective. Sting and Stewart did actually come to blows over “Every Breath You Take” as these approaches collided. Ultimately, while the sound of the album is remarkably consistent, it reflected this tension, with more experimentation and group energy on Side 1—including a song each by Copeland and Summers—and an almost unbelievable lineup of pop songs on Side 2.

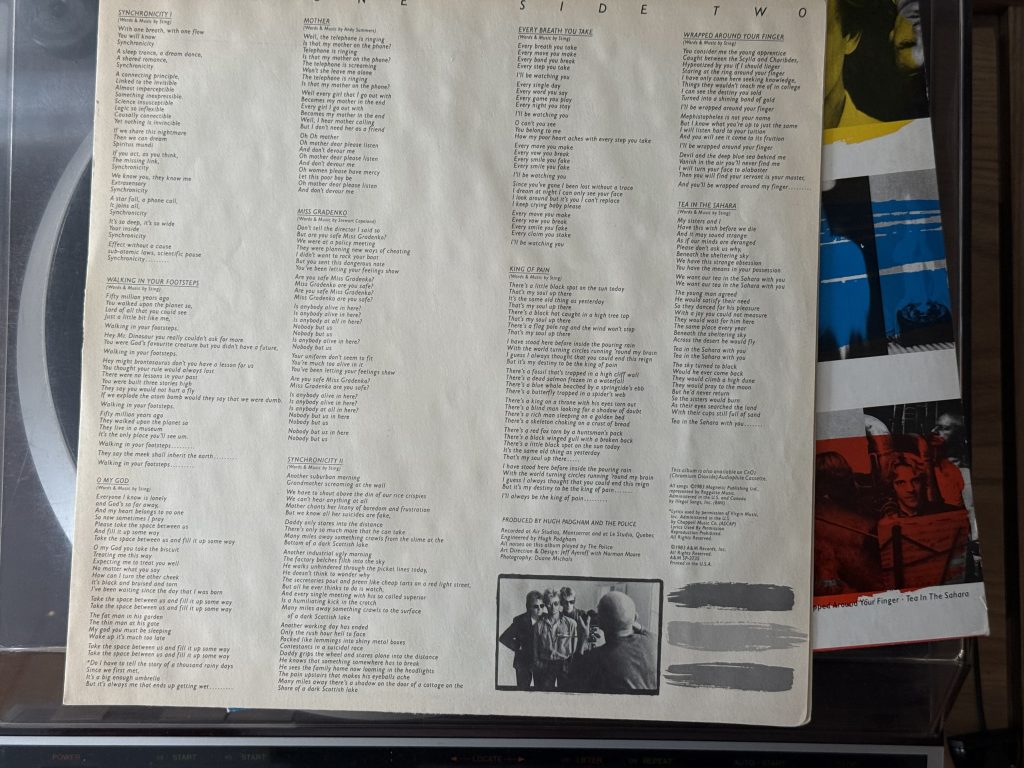

“Synchronicity I” starts side 1 off strong. A synthesizer part written by Sting, sounding enough like a marimba to throw off listeners and reviewers, plays for six bars in 3/4 time, with Stewart’s cymbals coming in on the last two bars. Then the drums and the bass come in with an all-out assault, with Andy’s guitar providing washes of texture behind it all. Here the benefits of Padgham’s approach can be heard, as each musician takes their intensity to the utmost in a way that would almost have been painful if they were all playing in the same room. Sting’s vocals are dual tracked in harmony on the verses and overlap each other on the chorus, with vocals in the right and left ear of the stereo mix that seem to tumble over each other in their speed to express their ideas: “A connecting principle / Linked to the invisible / Almost imperceptible / Something inexpressible/Science insusceptible / Logic so inflexible / Causally connectable / Nothing is invincible.” Sting was reading philosophy again. Returning to the works of Arthur Koestler, whose The Ghost in the Machine had lent the prior album its title, he found The Roots of Coincidence, a 1972 work that argued that some parapsychological phenomena should be investigated more closely through the lens of modern physics and built on Carl Jung’s work on the concept of synchronicity. Sting built on this concept of apparently unconnected events appearing to have a deeper connection throughout the first side of the album.

“Walking in Your Footsteps” settles down the tempo considerably, and dials back the intensity of the arrangement. There’s a loping bass and percussion underlay (again, likely synths), with a flute overtop and washes of guitar that sound like great bellows from some ancient animal. It turns out that is exactly what is on Sting’s mind, as he contemplates the rule of the dinosaur and their fall from power, and wonders “don’t you have a lesson for us.” One of his more direct expressions of anti-war sentiment, he wonders “if we explode the atom bomb/would they say that we were dumb?” Stewart keeps time during the verse by hitting the drumsticks together, and emphasizing the turn into the third verse with hits on the tom. This was one of the songs that the band continued to assemble until late in the game, to the point that the album’s lyrics sheet included a quatrain at the end that was recorded but omitted from the final mix: “Fifty million years ago/they walked upon the planet so/They live in a museum/It’s the only place you’ll see ’em.” (You can hear some of the alternate takes on the 2024 deluxe reissue of the album.)

I’ve read reviews of the album that talk about “Synchronicity I” as a jazzy song, perhaps because of the 3/4 meter, but “O My God” feels more tethered in the jazz idiom to me. That’s only appropriate, since it is the very last of the songs from Sting’s jazz fusion band Last Exit to be re-recorded by the Police. The version by the Police couldn’t be further from the Last Exit version, though; instead of Hammond B3 organ and jazzy chord changes, we get a tight chromatic bass line and a rewritten, considerably more concise lyric sheet. The line “How can I turn the other cheek / It’s black and bruised and torn” has been on my mind a lot lately; in the original version it’s a subliminal lament in the last verse, but here’s it’s almost howled in the second as the lead-in to the chorus “Take the space between us/and fill it up, fill it up, fill it up.” The other thing providing the jazz impetus is the saxophone. Sting’s playing has gotten considerably better since Ghost, and the sax lines here are tight, concise in some places and Coltrane-esque in others … and thankfully much better in tune. The guitar provides washes of sound and syncopated rhythm behind the bass and, especially, Stewart’s drums. (The snare pattern that introduces the second verse is one of the all time great moments from a great drummer.) The other thing to love about this song, despite what I saw as a very naïve 10-year-old as borderline blasphemy in the lyrics, is the humor in it all. You have “O my God you take the biscuit,” AND you have the recapitulation of “Do I have to tell the story of a thousand rainy days since we first met?” from “Every Little Thing She Does is Magic”—only here addressed to God. And then, of course, a free jazz freak out courtesy of layers of Sting’s saxophone, ending in an ascending scale up to the fifth, from which we drop a fourth into the key signature of the next song.

There’s definitely humor under the middle eastern guitar riff and screamed lyrics of “Mother,” but it might take a while to find it. Another Andy Summers song that Sting would not sing, Andy has said in interviews that it was in fact about his mother. It’s also easily read as being about the tense relationship between Summers and Sting; the vocal, with its note of deranged exasperation, could as easily be about an overbearing bandmate. The vocal filter used by Padgham here lends an edge to Andy’s “mother”s, especially the one in the lowest end of his range and the almost comical one that precedes the final verse. By contrast, Stewart’s “Miss Gradenko” is far less experimental and more likable. With a brilliant fingered guitar part throughout the verse and a locked-in bass and drum section, the story of the Soviet bureaucrat who seems “much too alive” in her uniform comes to life in the dual vocals from Sting and Stewart. It seems like it’s over too quickly.

Then there is a howl from the guitar, signaling “Synchronicity II.” Originally intended to proceed directly from “Synchronicity I” via a murky synthesizer interlude later named “Loch,” this bookend to the first side gives us the story of the narrator of “On Any Other Day” turned up to 11. Facing humiliation, frustration, and the end of love both at home and work, as the narrator drives home to “the pain upstairs that makes his eyeballs ache” we get the visual of something rising to the surface of a dark Scottish lake, as if synchronously called into life by his submerged rage. It’s all accompanied by the most straight ahead rock music the Police ever recorded. The music shifts from F♯ minor in the chorus (with Sting howling a wordless minor 3 – supertonic – subtonic) into F♯ major in the verse and back into minor, ending on an endless repetition around the fifth, leaving the synchronous rage and pain unresolved. It’s full of dark comedic touches in the verse (“We have to shout above the din of our rice krispies”) and near-apocalyptic fury in the instruments. It’s all very operatic. A wide eyed younger me had no idea what to make of it; I only knew the lyrics made me as uncomfortable as the music made me excited.

Side two opens with “Every Breath You Take,” the Police’s best-loved, most successful song (in 2010 it was estimated to generate between 25% and 30% of Sting’s publishing income), and the most unsettling song ever sung from the perspective of a stalker. The song itself was hard to nail down, as we’ve seen. After struggling to recreate it in the studio, the band agreed to work from the basic demo, but it needed a guitar part instead of the original organ that Sting had used. Sting told Andy “Go and make it your own.” Andy recalls, “I was kind of experimenting with playing Bartok violin duets and had worked up a new riff. When Sting said ‘go and make it your own’, I went and stuck that lick on it, and immediately we knew we had something special.” The guitar riff he came up with is simple – tonic to supertonic to mediant, but stepping down to the dominant between each note – and then repeating the pattern in two other modes before returning to the major scale. If “Synchronicity II” reflected anger over the dissolution of his marriage—a common reading of the album as a whole—“Every Breath You Take” seems to be stuck in the bargaining phase of grief as he sings “Oh can’t you see/you belong to me?” Sting himself told NME that it was “a nasty little song, really rather evil.” That it transcends all the circumstances of its origins and the sardonic irony of its lyrics has everything to do with the bridge (“Since you’ve gone I been lost without a trace”) and those descending single piano notes that underscore it, in which we hear the deep anguish at the heart of it all. The song went to Number One, giving the band their only chart-topping hit, and it stayed there for eight weeks.

That anguish leaps off the edge of the cliff of grief and into full blown despair on “King of Pain,” which continues Sting’s exploration of symbolism and unexplained synchronous events in a song that found metaphors for a darkened soul in everything from sunspots to a “flagpole rag.” The arrangement here begins in minimalism, bass and piano rocking back and forth on two notes with a marimba (or synth) in counterpoint; Stewart and Andy join on the second verse, still restrained until the chorus when the guitar finally rings its chords. It’s a literate exploration of an adolescent kind of pain, and ten to eleven year old me ate it up. (I especially thought the bit at the end, when the narrator repeats “There’s a little black spot on the sun today/It’s the same old thing as yesterday”) from the beginning over a descending glissando in the guitar, implying a perpetual, personal Sisyphean hell, was deep. I was a depressed kid.) Lots of people liked perpetual Sisyphean hells, but not as many as liked stalkers; this one went to Number One on the Mainstream Rock chart but topped out at Number Three on the Hot 100.

The last song of this side to be released as a single, “Wrapped Around Your Finger” was also a top 10 hit, peaking at Number Eight. It was also the sound of the life being slowly strangled out of the interplay among the trio. Copeland’s drum flourishes are all but gone; his rhythmic genius is still present as he chooses different beats to accent with a hit to the tom or the cymbal, but none of the splashy flourishes from the old songs are present. And Andy Summers’ guitar plays precisely on the hook in the opening verse—over the synthesizer—and echoes at the end of each phrase, but otherwise is kept on a tight leash until the final verse. Even then the rising energy is conveyed by playing a single note over and over again. It’s perhaps musically appropriate for a song that is all about control; the lyrics revisit the themes first explored in “Secret Journey” of someone seeking wisdom and knowledge, but this journey does not end in enlightenment, only in bondage. The narrator flips the Faustian story at the end, having “listened hard” to the tuition of the unnamed master until he gains the power to reverse the relationship and take control. But the central metaphor Sting uses throughout, of being wrapped around the finger of the other, can also be read as a ring; in the context of the failing relationship of “Every Breath” and “King of Pain,” it’s hard not to view “Wrapped Around Your Finger” as an exploration of emotional bondage in the aftermath of a failed relationship.

If “Wrapped Around Your Finger” is the end of the life of the trio, “Tea in the Sahara” is its afterlife—wandering endlessly in the desert, an eerily arid soundscape constructed of the drums and bass with only the echoes of a guitar washing across the sky with a distant saxophone (almost sounding like a shofar). Sting was, at this point in his writing career, superb at plucking out bits from his reading and turning them into the raw materials for his grand theme. In this case, the grist for the mill was Paul Bowles’ novel The Sheltering Sky, which yielded the entire plot of the song. The story of the three sisters who danced for joy when the stranger promised to return to their company to take tea, reduced to burning in the desert “with their cups still full of sand” when the stranger never returns, feels like the ultimate metaphor for the demise of love and of this band.

Synchronicity is a record that started as many things as it ended. For one, it marked the end of the Police’s studio album output—though not all its studio output! There was an abortive attempt to record a sixth album in 1986 that went poorly; Stewart Copeland broke his collarbone the night before the sessions in a horse accident, and the hoped-for magic didn’t materialize in the sessions. Ever artisans, the band accepted that they weren’t going to build a table in the sessions, but came away with two lovely chairs—the 1986 remade versions of “Don’t Stand So Close to Me” and “De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da.”

For me, this is the album that started listening me to the Police, when our babysitter brought it over one day. I was ten and my sister was seven or eight, and while we weren’t ready for the first side (up until that point, music in our family was either classical radio—thank you, WGH and WHRO—or the easy listening station in the car), I connected hard with the second side. It started me opening my musical ears, without which I wouldn’t be writing this series.

This album also, by closing the door on the Police, started Sting down a solo path, going in a very different direction. After years of punk, prog, and new wave, he decided to return to his jazz roots. But where, exactly, was jazz in the mid-1980s? There were very definitely two competing visions for where jazz music was headed, and that’s what we’re going to step aside and listen to next week and the following.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

BONUS: The first of this week’s bonuses really is a bonus track; it was left off the vinyl pressing for reasons of running time, but included on the cassette and CD versions. It’s probably the most darkly funny lyric Sting ever wrote, and you can definitely hear his jazz roots in the waltz-time arrangement. Here’s “Murder by Numbers”:

BONUS BONUS: Sting did a few recordings with jazz legend Gil Evans (yes, that Gil Evans) and his orchestra in the late 1980s, and this absolutely killer arrangement of “Murder by Numbers” was one of the outcomes:

BONUS BONUS BONUS: I always thought it was an urban legend, but the recent massive Synchronicity Deluxe Edition included this track, an anti-war version of “Every Breath You Take” with new lyrics and vocal recorded by Sting in 1985 and included on a “Spitting Image” collection. Here’s “Every Bomb You Make.”

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS: The reason Sting’s publishing revenues are so overwhelmingly dominated by “Every Breath You Take” may well be due to the song’s afterlife. In 1997 a young Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs wrote a farewell ode to slain rapper “Biggie” Smalls around Andy Summer’s guitar lick and the verse melody of the song, titling it “I’ll Be Missing You.” It was a number one song for 11 weeks. (Stereogum’s The Number Ones column does a great job of writing about Combs’s song; I like columnist Tom Brennan’s take on “Every Breath You Take” too.) Sting sang it with Puff Daddy (now calling himself “Diddy” and awaiting trial on allegations of sexual assault) at the 1997 MTV Video Music Awards in a performance that opened with a rendition of Samuel Barber’s Agnus Dei (his choral setting of “Adagio for Strings”); here’s that moment.