Album of the Week, September 23, 2023

In this short series about funk, Gil Scott-Heron would seem to be an unlikely choice. A poet, militant, novelist, spoken-word artist, Scott-Heron was not a musician by calling. Indeed, he called himself a “bluesologist,” a scientist concerned with the origin of the blues. But, thanks to two important collaborations, Scott-Heron has a place not only among the progenitors of funk but among the ancestors of hip-hop.

Gil Scott-Heron was born in Chicago in 1949, to an opera singer mother and a Jamaican soccer player. His parents separated when he was young, and he went to live with his grandmother Bobbie Scott, a civil rights activist who introduced him to the works of Langston Hughes and to the piano, in Jackson, Tennessee. On his grandmother’s death, he moved to live with his mother in The Bronx. He went to DeWitt Clinton High School but transferred to the Fieldston School on a full scholarship for writing. He was known as much for his acerbic wit and keen sense of social irony as his writing; when asked in an admissions interview how he would feel if he saw one of his classmates drive by in an limousine while he walked, he asked the interviewer, “Same way as you. Y’all can’t afford no limousine. How do you feel?” He attended Lincoln University, a historically black university in Pennsylvania, because Langston Hughes had done so.

It was at Lincoln University that he met one of his most important collaborators, the musician Brian Jackson, with whom he formed a band. Jackson was to collaborate with him throughout the 1970s. At Lincoln, he also attended a performance by the Last Poets, an incendiary spoken word ensemble who are today held to be among the forerunners of hip-hop, and asked them “Listen, can I start a group like you guys?” He left school to work on his debut novel, Vulture, and moved to New York City, where he met the other significant collaborator, jazz musician and producer Bob Thiele.

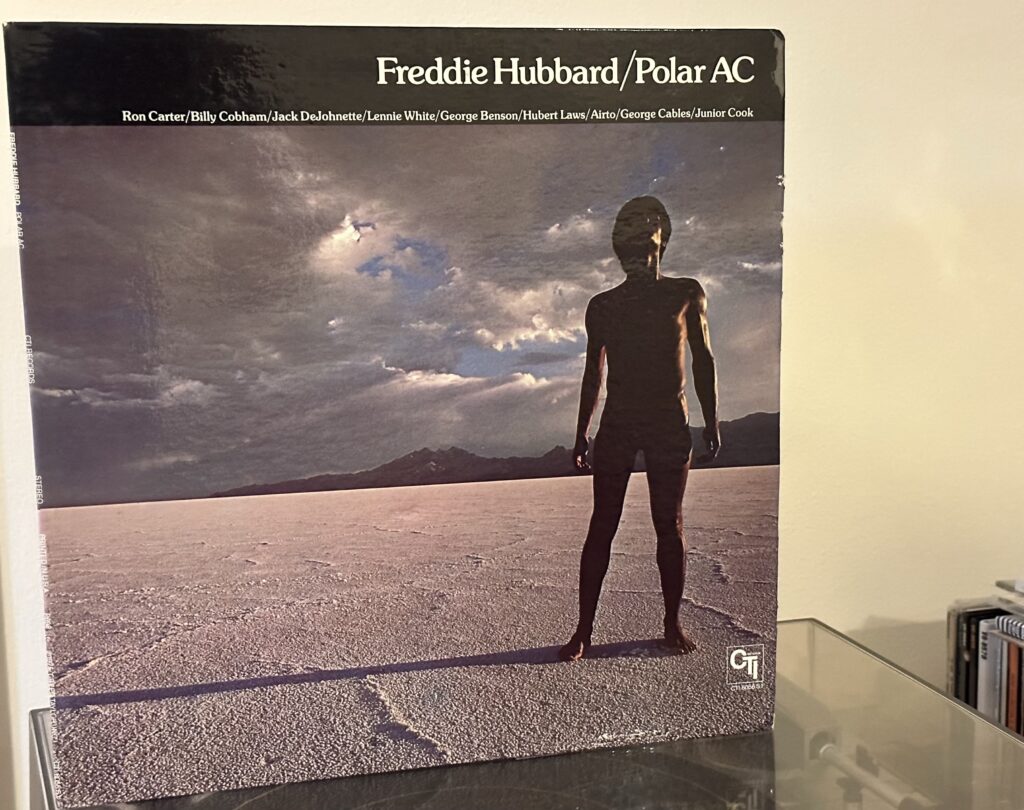

Thiele had gotten his start in the record business working for Creed Taylor, and served as the head of Impulse Records following Taylor’s departure for Verve. In his eight years at Impulse, he produced the most significant of John Coltrane’s late works, including Coltrane, John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman, Duke Ellington & John Coltrane, Impressions, Crescent, A Love Supreme, Meditations, and Ascension. He also produced many other significant albums for Impulse, which was by this point a division of ABC Records, including Freddie Hubbard’s The Body and the Soul, and co-wrote the song “What a Wonderful World.”

The collaboration with Louis Armstrong on this (eventual) hit song led to a breakdown in relations between Thiele and ABC Records president Larry Newton. Apparently Newton was expecting a Dixieland style album from Armstrong, and when he learned that Thiele was recording him performing “Wonderful World,” a ballad, an argument began that escalated into a screaming match, with Newton ultimately being ejected from the recording studio and left yelling and banging on the door outside. Thiele left ABC shortly after and started his own label, Flying Dutchman. One of the first artists he convinced to record with him was Gil Scott-Heron.

The artist recorded three albums for Flying Dutchman, as well as today’s release, a 1974 compilation drawn from the first three releases after Scott-Heron departed for the Strata-East label. Gil’s debut album on Flying Dutchman, Small Talk at 125th and Lenox, was a live session of poetry with accompaniment from Eddie Knowles and Charlie Saunders on conga and David Barnes on percussion and vocals, as well as Thiele himself on piano and guitar. The album did not chart, but it did feature the poems “Whitey on the Moon” and “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” performed as spoken word pieces with percussion accompaniment.

The two albums that followed were entirely different. For Pieces of a Man, Brian Jackson joined as musical director, and Thiele assembled an enviable cast of musicians to join them, including Ron Carter on electric bass, Hubert Laws on flute, Bernard Purdie on drums, and Burt Jones on electric guitar. Jackson’s musical perspective combined with Scott-Heron’s bluesy melodic writing is what connects this album to the funk of Sly and the Family Stone—along with a similar perspective on race relations. For the album, Scott-Heron re-recorded “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” with the new band, and the combination of Carter on bass, Purdie on drums, Hubert Laws’ anxious flute obbligato, and Scott-Heron’s intense spoken word work laid the blueprint for hip-hop. Carter’s bass in particular is tense and apocalyptic throughout the track, underscoring the fierce conflict in Scott-Heron’s poem between our commercial culture and the economic struggles of Black people:

The revolution will not be right back after a message about a white tornado, white lightning, or white people

You will not have to worry about a dove in your bedroom, the tiger in your tank, or the giant in your toilet bowl

The revolution will not go better with Coke

The revolution will not fight germs that may cause bad breath

The revolution will put you in the driver’s seatThe revolution will not be televised

Gil Scott-Heron, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”

Will not be televised

Will not be televised

Will not be televised

The revolution will be no re-run, brothers

The revolution will be live

As if to underscore the diversity of Scott-Heron’s lyrical agenda, “Sex Education: Ghetto Style”, from his third album Free Will, is another spoken word poem that slyly pokes fun at his own sexual coming of age. The performance style is closer to the music of Small Talk with the important addition of Jackson on flute. The rest of the Pieces of a Man band, except for Carter, returned for this album, and it featured a blend of spoken word and more traditional songs, including the next track, “The Get Out of the Ghetto Blues,” with Jackson’s bluesy piano complemented by David Spinozza’s guitar.

“No Knock” comes from the same sessions, but is spiritually closer to “Revolution” in spirit and to “Sex Education” in conception, with Jackson on flute alongside percussionists and Scott-Heron’s rap. The original album features a spoken word intro to the performance from Scott-Heron that sets the context:

Um, we want to do a poem for one of our unfavorite people, um, who’s now the head of the, uh, Nixon campaign. He was formerly the Attorney General named John Mitchell. … no-knock, the law in particular, was allegedly, um, aheh, legislated for black people rather than, you know, for their destruction. And it means, simply, that authorities and members of the police force no longer have to knock on your door before entering. They can now knock your door down. This is No Knock.

Gil Scott-Heron, “No Knock”

The compilation now transitions into one of Scott-Heron’s greatest collaborations with Jackson, the great “Lady Day and John Coltrane” from Pieces. Scott-Heron’s second album was the most introspective of his works, featuring multiple songs from the perspective of different sides of the Black experience, as well as this joyful, bluesy celebration of the power of jazz music. For me, the musical highlights are Carter’s bass line and Jackson’s Fender Rhodes solo after the second verse.

The compilation follows this track with the title track to “Pieces of a Man,” a ballad on acoustic piano and bass that tracks the disintegration of the narrator’s father, describing his violent outbursts and his despair at being fired from his job, leading to his arrest. The song might be Scott-Heron’s masterwork, fusing powerful metaphoric writing with an impassioned vocal. Scott-Heron’s narrator is only one of the examples of broken Black males to be found in his writing; “Home is Where the Hatred Is” (the following track) is written from the point of view of a heroin addict, who struggles to get clean while recognizing that returning “home” to his sobriety means having to confront the pain of his existence: “Home is where the needle marks/Tried to heal my broken heart/And it might not be such a bad idea if I never/Went home again.”

“Brother” flips the perspective again, calling out hypocritical Black men who take on the outward trappings of Black liberation while not actually helping their brothers and sisters, in one of the earliest spoken recordings on this set. The compilation pairs the poem with another track from Pieces, but “Save the Children” is short on specifics on how exactly the children should be saved from the harsh reality of African-American life that will confront them when they grow up, though it’s another gorgeous collaboration with Jackson.

“Whitey on the Moon” might be the most famous of Scott-Heron’s poems after “Revolution,” and for good reason, as he points out the uncomfortable gulf between the accomplishments of the Apollo program and the economic state of Black America. As I’ve written before, I’m a NASA kid, and proud of our accomplishments in space, but Scott-Heron’s poem points out that in our national choices on spending priorities in the 1960s between the space race, Vietnam, and Johnson’s War on Poverty, he could only see outcomes from two of the three.

The compilation closes with “Did You Hear What They Said?” from Free Will. The darkest of Scott-Heron’s early collaborations with Brian Jackson, the paean for a dead Black man—“They said another brother’s dead/They said he’s dead but he can’t be buried”—might be the most desolate lines he wrote. Accompanied by Hubert Laws’ flute, the closing thought, “This can’t be real,” reflects Scott-Heron’s loss of hope following the death, which evokes both Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination and the deaths of Black men from crime and police brutality.

The compilation as a whole is a powerful and complex representation of Scott-Heron’s legacy, and a good introduction to his work. But it deliberately ends in denial of the hope represented by some of his early songs, foreshadowing Scott-Heron’s own journey. His post-Flying Dutchman recordings with Brian Jackson and the Midnight Band were triumphant, but they acrimoniously split in 1980. Scott-Heron recorded sporadically after, and seemed to spiral slowly downward. Addicted to crack cocaine, he spent time in prison for drug possession, and recorded one last album in 2010, the harrowing I’m New Here, before his death in 2011, following reports of pneumonia and that he was HIV positive.

There are no easy answers in Gil Scott-Heron’s story, but I prefer to hold onto the gestures toward hope in his best songs. Next week we’ll visit another album from a performer struggling with addiction, who nevertheless continued to make vital, even joyous music.

There wasn’t an official playlist or full-album version of this compilation on YouTube, oddly, so I made my own. You can listen to it here: