Album of the Week, July 19, 2025

The mid- to late-1950s were a good time, compositionally, for Thelonious Monk. Following the critical success of Brilliant Corners, he released a series of additional albums, including the 1957 Monk’s Music with John Coltrane and Coleman Hawkins, that documented his growing list of original compositions. At the same time, his works were being covered, and celebrated, by a growing list of jazz luminaries, including Miles Davis on his ‘Round About Midnight, the first Columbia recording of his first great quintet and made at the same time as Workin’, Cookin’, Steamin’, and Relaxin’.

But not everything was idyllic. In 1958, Monk and the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter were detained by police in Delaware en route to a gig, who beat him with a blackjack when he refused to answer questions. And in 1960, his relationship with Riverside Records soured over royalties, which would ultimately declare bankruptcy in 1963 following cofounder Bill Grauer Jr’s sudden death. Monk ended up signing to Columbia Records in 1962. It was a great move commercially for Monk, as the larger label could devote more resources to promoting the genius. (He was to have appeared on the cover of Time Magazine in November 1963, but the story was delayed due to the assassination of John F. Kennedy; it ultimately ran in February 1964, at which point he became one of the only modern jazz musicians to ever be featured on the cover.) But his well of new compositions dried up, and many of the records featured re-recordings of earlier compositions with his new band, featuring Charlie Rouse on tenor, John Ore on bass, and Frankie Dunlop on drums.

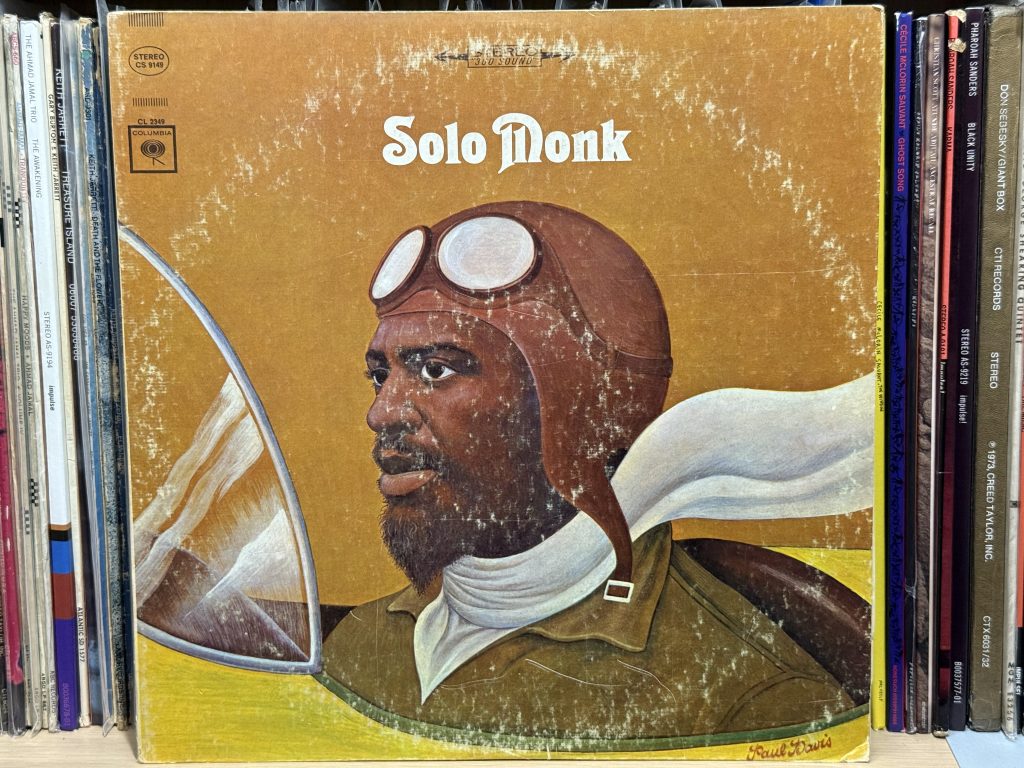

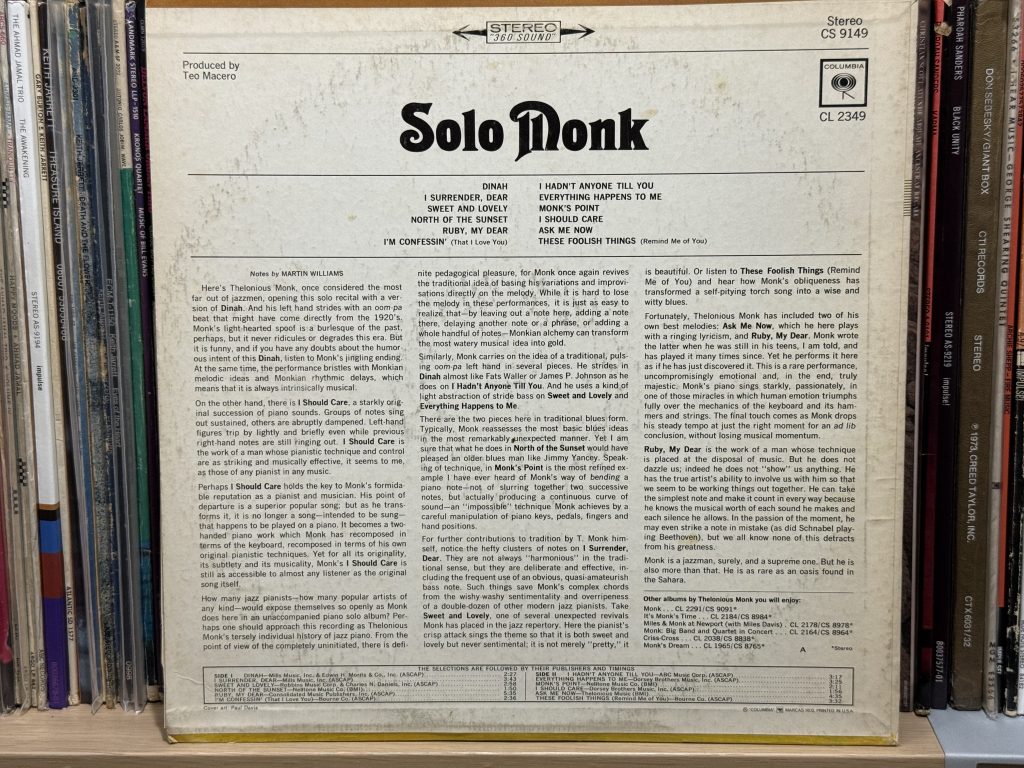

So we come to Solo Monk, recorded in 1964 and 1965, in the middle of his eight-album run for Columbia, and featuring Monk on solo piano on a program of his own compositions and a set of unusual standards. The program kicks off with “Dinah,” a popular song from 1925 by Harry Akst with lyrics by Sam M. Lewis and Joe Young, and which was more associated with Louis Armstrong and Cab Calloway than with the bebop intelligentsia. The anonymous liner notes for Solo Monk sound a note of surprise at the stride flavor of Monk’s interpretation, which should be no surprise to us after our the last few weeks. The piece as a whole is a light-hearted romp that does prove that Monk has a sense of humor, but it’s more than just a joke. Though the first part of the work has the propulsive drive and left-hand block chords of the old stride piano style, giving the feel of a 1930s show tune, the end suddenly shifts to a freer style and we see through Monk’s eyes the title character, no longer a caricature but someone fully modern and distinctive—complete with a closing trill on the highest notes of the piano. As the liner notes say, Monk had a sense of humor, but that’s not all that’s shown here.

“I Surrender, Dear” is familiar to us, having appeared on Brilliant Corners. This version has fewer of the outer eccentricities that appeared on that album. We don’t get anything like stride until Monk gets to the B section, and it isn’t until the second repetition that he starts to elaborate the melody, complete with some of the flat-finger seconds and clusters—and some brilliant tossed-off runs. He takes the last chorus with a good deal of rubato and an octave-long run down the keyboard.

“Sweet and Lovely” (by Gus Arnheim, Charles N. Daniels and Harry Tobias) is one of those tunes that seems to lurk in the collective memory; I couldn’t have told you the tune from the name, but it’s instantly recognizable (probably from old “Tom and Jerry” cartoons). Monk’s rendition follows the same pattern as “I Surrender, Dear,” with the first verse played straight (albeit with stride left hand, a tremolo in the right hand, and the melody in octaves). The improvisation on the third chorus, however, turns the song into a new composition, with a single phrase repeated in rhythm across the whole verse. For the final run through, Monk returns to the tremolo effect, but again brings us into a deeper emotional moment in the final rubato section.

“North of the Sunset,” only recorded on this album, is a Monk blues with a syncopated opening theme, full of pauses. The B section takes the melody and elaborates it into a fuller sound. Monk only gives us two repetitions of the whole thing; the track ends at 1:50 with the sound of the pedal dropping back into place. He saves his energy for a solo version of “Ruby, My Dear,” which immediately follows. Written in 1945, it’s one of his oldest compositions and one that he returned to often; we previously heard it on Monk’s Music. Here the improvisation is limited: some alternate rhythms in the B section, a few accelerated and double time sections in the final repetition, and a dip into a new key at the very end. Otherwise we are left to soak in the ballad.

“I’m Confessin’ (That I Love You),” a jazz standard with origins in a tune recorded by Fats Waller, gets a similar treatment. Here Monk’s exuberance peeks through a bit more in the hard-swinging syncopation, the spontaneous arpeggios in the B section as it turns into the chord change, and the extended bridge linking the first and second repetitions. Monk’s improvisation on the second repetition seems to take flight with two voices, while still anchored by the steady chords of the left hand. Again, a brief pause and a rubato run down to a final chord, followed by a high, far-off twinkle.

Ray Noble’s “I Hadn’t Anyone Till You” takes a freer initial approach to the late 1930s popular song, at least until the B section when the steady stride chords make their return. The end, with a pause for effect before a final declaration that swoops up the entire keyboard, lands in a key of joyous wonder.

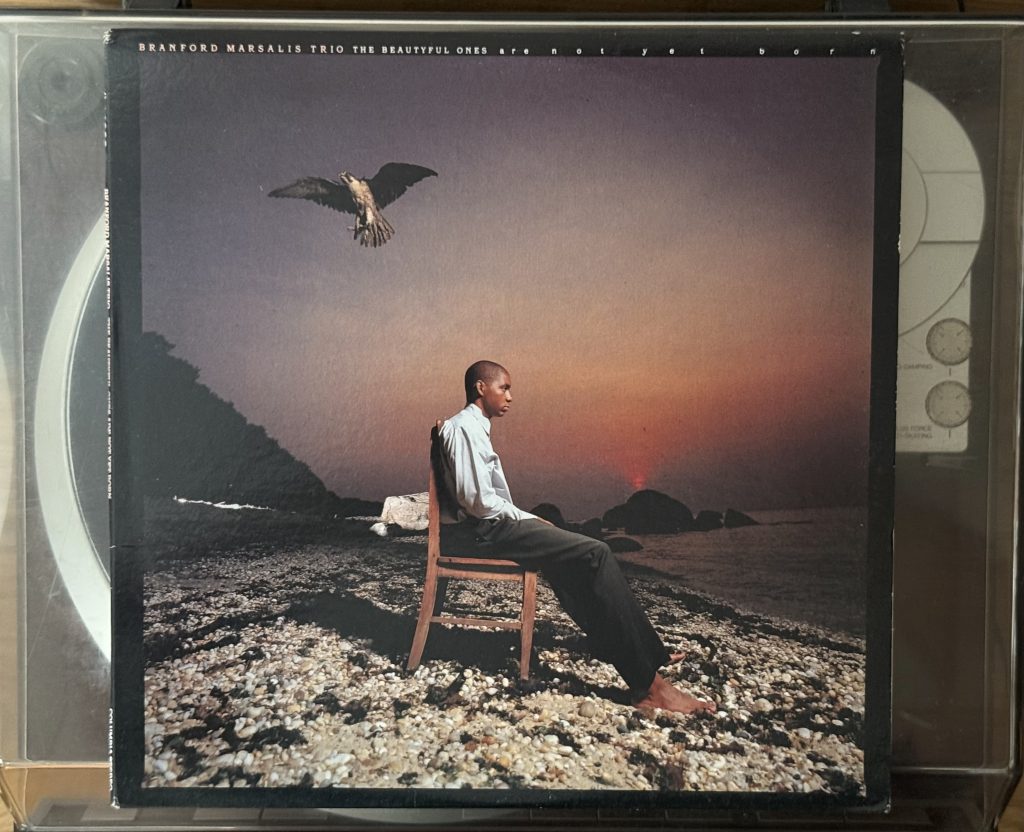

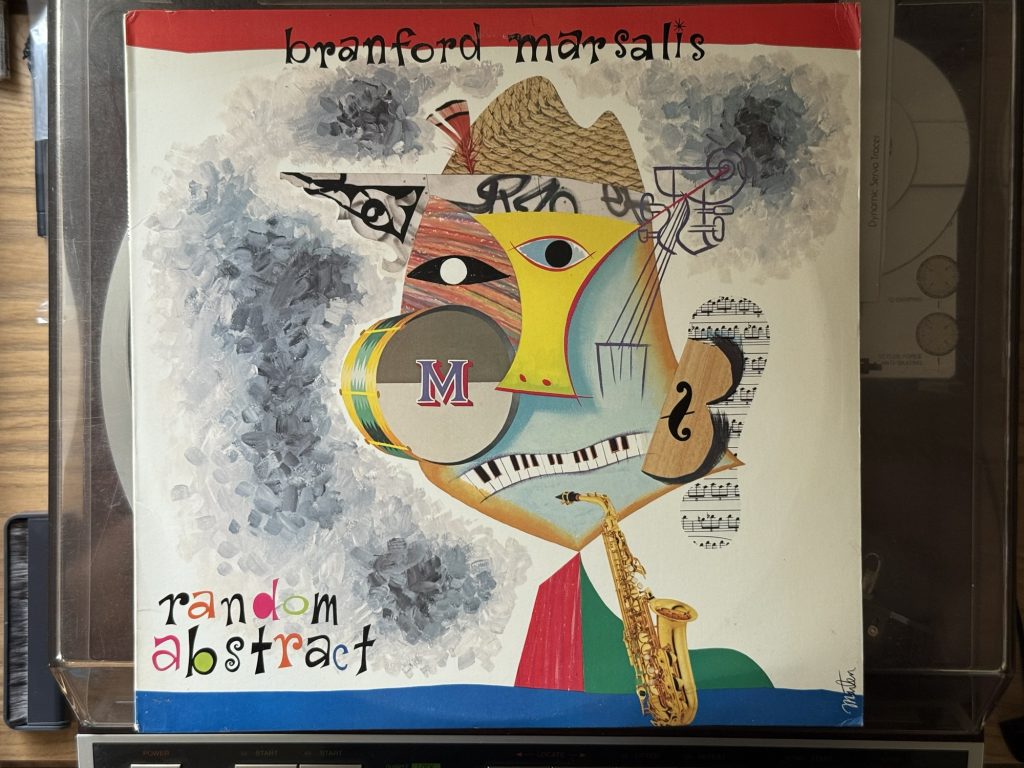

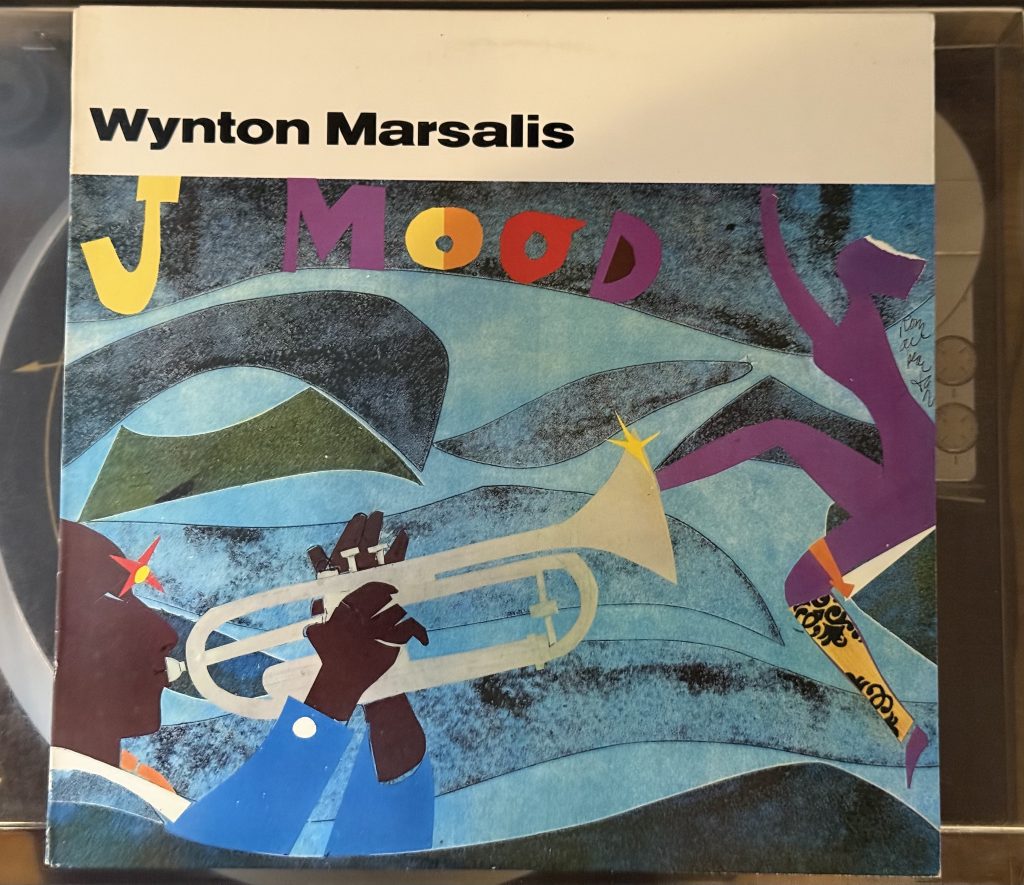

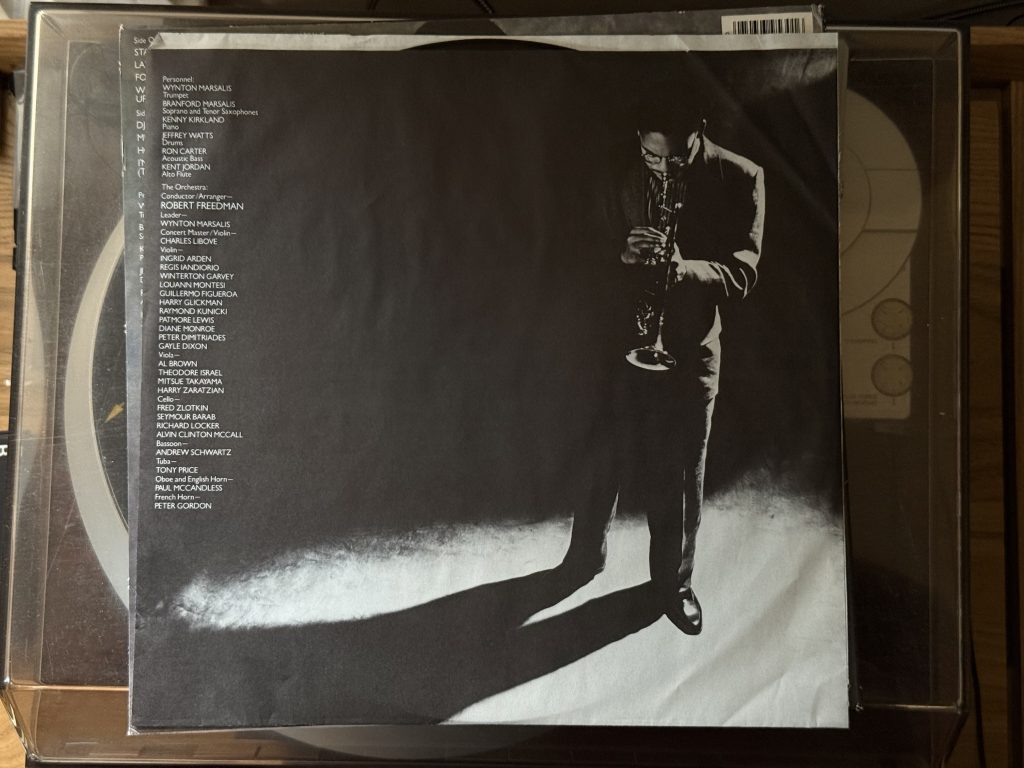

We’ve heard “Everything Happens to Me” before, on Wynton Marsalis’s Standard Time Vol. 3. This version is briskly unsentimental by comparison, but still retains the loveliness of Tom Adair and Matt Dennis’s melody, even as it swings into something a little more dancelike, if one can imagine Monk’s eccentric shuffle as a dance. And as he steps away from the strict rhythm into a free moment for a while, suddenly it is a dance that ends with that same high note of wonder.

“Monk’s Point” is another Monk blues, this one featuring a repeated “bent note” (as bent as notes played on a keyboard can get). It’s a spirited tune that seamlessly flows from the theme into a sort of hybrid ragtime reel; as with “North of the Sunset,” it’s in and out in less than two minutes, but sees far more development in those two minutes.

“I Should Care,” the standard from Axel Stordahl and Paul Weston with Sammy Cahn, has been covered by everyone from Bill Evans to Johnny Hartman to Frank Sinatra, and the interpretations usually skew to the sentimental or the jaunty. Monk steers away from both interpretations. His approach is less jaunty, more defiant; you can hear the determination to give the impression that the narrator is just sleeping fine, that he doesn’t go around weeping. But that twist ending—“And I do”—is present from the beginning of Monk’s interpretation, especially in the end as the moving parts fall away and we’re left with an aching suspended chord before the final resolution. All in two minutes.

“Ask Me Now” is the last Monk composition on the album, and the only one to get more than two minutes’ running time. It keeps good company with “I Should Care,” sounding like a more conventional ballad than “Ruby, My Dear,” but the constantly shifting tonality reminds us that Monk’s simplicity is usually complex even as his complexity often is in the service of something very simple. In this case, the melody is eminently singable, even as the tonality seems to shift like the facets of a crystal in sunlight. Monk takes some rubato into the final verse, and a splash of a high cluster chord together with a Woody Woodpeckeresque final run let us know the narrator’s demands ultimately grow increasingly insistent.

We last heard “These Foolish Things (Remind Me of You)” performed by Johnny Hartman, but again Monk takes a different interpretive path, shedding Hartman’s overt emotion for a more abstract interpretation. You can hear his tonal imagination at work in the chord sequence that ends the first chorus, the run that takes us into the bridge, the progression that seems to take us off a chromatic cliff into the final verse. The final bridge is taken freely in not-quite-double time for a moment, until it settles down for the final chorus, and one last surprise: a lingering chromatic chord that never resolves, fading into silence and the runout groove.

Monk would record three more studio albums for Columbia, but only the last one, Underground, would feature a significant amount of new works. Arguably, the most rewarding recordings from this period are the live recordings that document the band with Rouse, of which one (Misterioso Live on Tour ) was released while Monk was signed to the label. But he toured extensively during this time, and there have been other live recordings from this period, surfacing as recently as the last few years, that have been exceptional. We’ll close this series with one of those next week.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

BONUS: “Monk’s Point” received new life on the 1968 album Monk’s Blues in a big band arrangement by the inimitable Oliver Nelson. Here’s that arrangement: