Album of the Week, November 2, 2024

In the year following the V.S.O.P. tour, Herbie Hancock recorded a jazz-funk album, Sunlight, with the post-Headhunters band that appeared on his V.S.O.P. live album, plus Jaco Pastorius and Tony Williams. The album, which featured Herbie’s voice singing through a Sennheiser vocoder, was widely panned as being not only not jazzy, but not funky. (I will say that having heard him perform “Come Running to Me” live in concert a few years ago that the material here is stronger than the performances.) He was also playing traditional jazz in concert, and today’s record is one of the most unusual in his repertoire: a two-piano duet album with his successor in Miles’ band, Chick Corea.

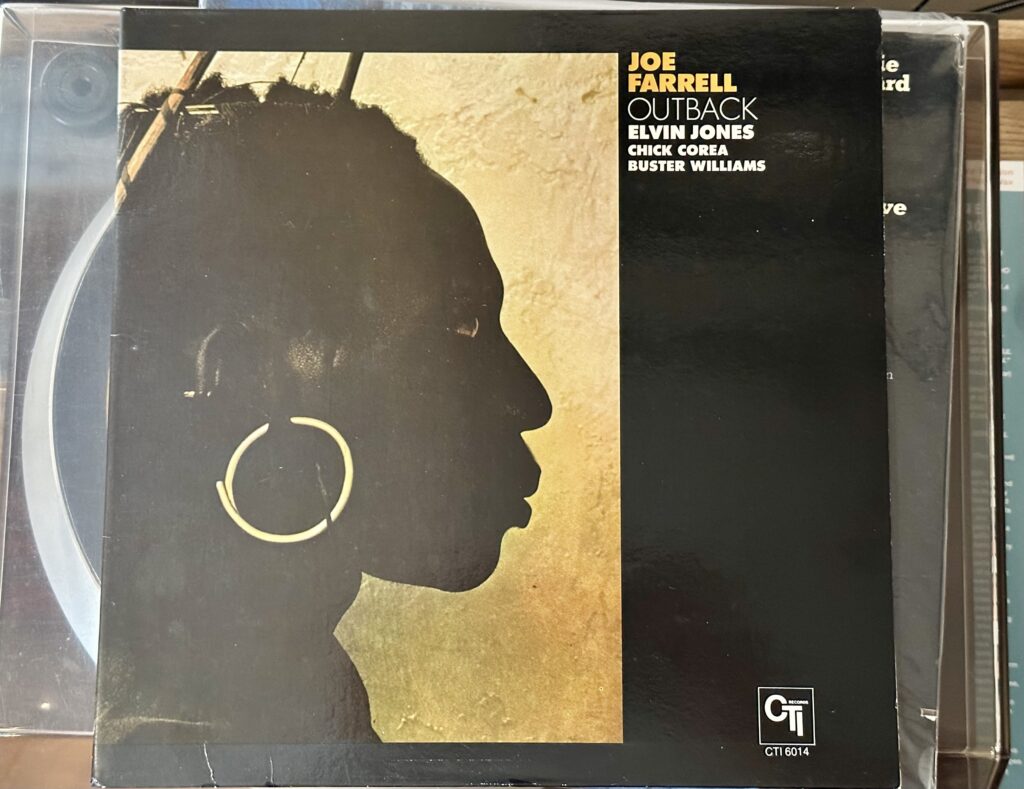

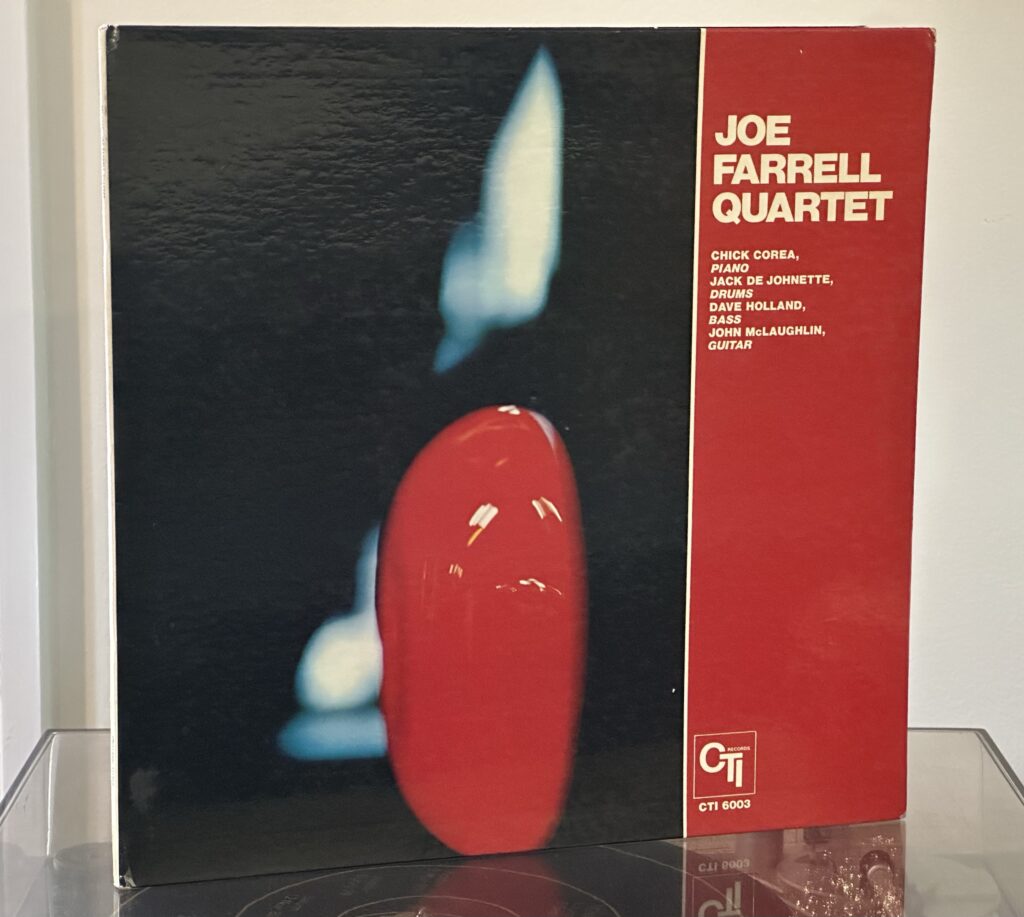

Armando Anthony “Chick” Corea was born in Chelsea, Massachusetts, to the north of what is now Boston Logan International Airport, in 1941, to a Calabrian family. His father had played trumpet in a Dixieland band in Boston, and introduced him to music and jazz at a young age. Corea moved to New York where he attended Columbia University and then Juilliard before dropping out so that he could perform more. He played in a number of different bands before joining Miles’ group during the sessions that became Filles de Kilimanjaro, and played with Miles until 1970. He left with Dave Holland to form a band, then in 1972 formed the Return to Forever band with Flora Purim, Airto, Stanley Clarke, and Joe Farrell. He played both jazz fusion and acoustic music through the 1970s, and in 1978 began what became a series of duo concerts with Herbie Hancock in which they performed in formal attire, playing each other’s compositions and jazz standards. This album was recorded live in a series of concert performances in San Francisco, Los Angeles, San Diego and Ann Arbor in February 1978.

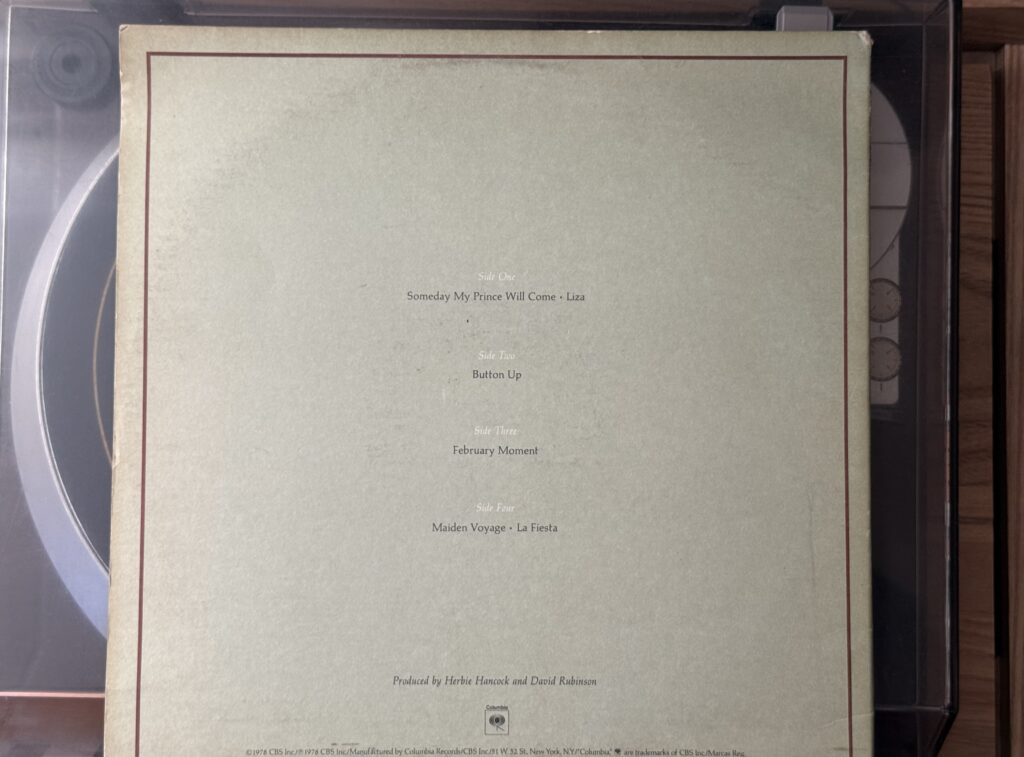

“Someday My Prince Will Come” illustrates the way the two great pianists approached the collaboration. In the opening few minutes, Corea (in the right channel, facing Hancock) plays freely as Hancock, listening carefully, accompanies him. At about the 3:30 mark the two finally swing into something approaching the chorus of the famous Snow White tune, but there’s still a lot of give and take between them as one idea after another enters, is imitated, and leaves. This is music to listen carefully to, and as you start to hear the imitative work it becomes fascinating. However, it does not lend itself to casual listening: with both pianists in the same octave and often improvising with runs and digressions from the tune, there are moments where it seems to almost scamper hither and yon, leaving the listener searching for the tune.

“Liza (All The Clouds’ll Roll Away)” starts a little more immediately; indeed, this is the only performance on the album that comes in at less than ten minutes. This one has a raggy flavor to it, with both pianists experimenting with stride style accompaniment on the Gershwin tune, until about the 4:30 mark when they begin experimenting with alternating short four or five note phrases, which then become alternating four bar phrases, quick flashes of improvisation and impromptu response. My favorite of these comes at 5:22 where Herbie plays a four-bar phrase in strong meter which Chick immediately accompanies with a clapped Latin rhythm. They keep the audience on the edge of their collective seats until the end, when they burst into rapt applause.

“Button Up,” credited jointly to Corea and Hancock, takes up the entirety of the second side and is a more introspective, and intricate, work, leaning into A flat minor. At the 1:35 mark Corea breaks into a minor key riff that Hancock begins to improvise over, and for a moment it seems like we might be in for a blues, but then they move on to a sonata-like interlude that tapers off into silence. Herbie breaks the silence with a fierce interlude that Corea responds to and they again approach a more rhythmic feeling, which Corea emphasizes by pounding out a thudding syncopated rhythm on middle C, which he dampens by pressing on the string with his other hand so that the tone sounds more percussive and less ringing. After interludes of more rhythmic and wistful music, they return to the thudding rhythm, this time with Herbie playing a melody that centers around the F while Corea continues to hold the C. The overall effect is something like a particularly inspired bit of Keith Jarrett solo playing; both players use the technique all the way through the last few minutes of the work.

“February Moment” is introduced by Corea, with a spoken appreciation for Hancock’s rare solo work. The piece, credited to Herbie alone, picks up where “Button Up” left off, only instead of a syncopated rhythm we get repeated left hand eighth note patterns in which the emphasis notes are played an octave up. Herbie’s right hand provides the melody, which is more of a reverie than anything else. About six minutes in, Hancock transitions away from the etude and begins playing a twelve bar blues, with the left hand playing a very slow fingered bass as the right provides different interjections above. The rest of the piece takes us from the blues into an absolutely furious interjection at top velocity and then back into the blues for a quiet conclusion.

The last two tracks, “Maiden Voyage” and “La Fiesta,” are played together as a single 30+ minute suite. As the notes from producer David Rubinson indicate, he decided to compress the music to fit the single side of the record rather than break them apart; as a result on my LP the sound of this last side is not as immediate as it is in the rest of the performance. I have to confess that this version of “Maiden Voyage” is not my favorite; Corea’s improvisations are busy and to me feel like interruptions of the oceanic sweep of the composition. But Herbie rolls with it, introducing new patterns that rise and fall like the waves against Corea’s runs. After about ten minutes, both pianists begin to improvise a new tune, a bridge between “Maiden Voyage” and “La Fiesta,” ultimately returning to the former tune for a brief interlude before beginning the latter in earnest. This time Herbie begins Chick’s tune, and Chick responds with an improvisatory aside that takes us into the ongoing performance. There are moments of noodling, of brisk Latin melody, of pathos, of thudded muted strings, of orchestral noise and (it must be said) some uninspired noodling in the 20-something minutes here. Again, this is music for close listening, and doesn’t really take off into a dance-like ecstatic rhythm until something like the last few minutes—but when it does, watch out because these are a few minutes of ecstasy like nothing else on the album.

Herbie Hancock continued to alternate jazz-funk records with acoustic jazz records into the early 1980s, but there was increasingly a sense that the jazz-funk side was becoming a priority. There were still plenty of jazz purists around, though, and acoustic jazz was about to make a resurgence. We’ll hear an important moment in that transition next week.

You can listen to this week’s album here: