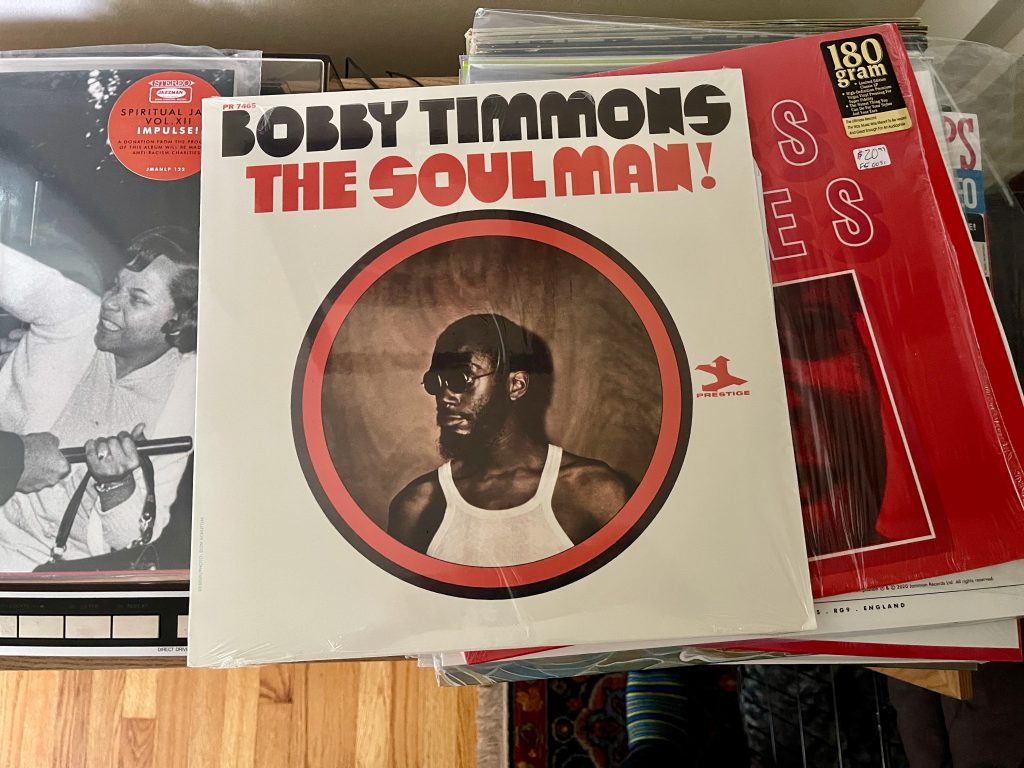

Album of the Week, July 2, 2022.

We’ve been listening to a string of masterpieces lately. E.S.P., Speak No Evil, and Maiden Voyage are all high on the list of 1960s jazz albums, and stand as top albums from each of their producers, and The All Seeing Eye is easily up there too. But most of these musicians were recording multiple albums a year, and no one is that hot for that long. And, jazz being jazz, many of them also appeared on other peoples’ records. Records that are fun to listen to but nowhere near in the same league.

Such is the case with The Soul Man, today’s album of the week. Bobby Timmons isn’t a well known name in jazz today, but he was white hot in the early 1960s. Having been a member of the best ever Jazz Messengers group that Art Blakey ever assembled, which also featured Wayne Shorter, Lee Morgan, and Curtis Fuller, and in between basically starting the soul jazz revolution as a member of Cannonball Adderley’s group with his compositions “Moanin’,” “This Here,” and “Dat Dere,” it would seem that he could do no wrong.

Except, of course, when he was consumed by his demons. He had been hooked on heroin since his early days in Blakey’s band, and was such an avid drinker that he missed part of his first recording sessions with Adderley. His musical development, according to AllMusic’s Scott Yanow, basically stopped in 1963, and while he continued recording for Riverside and then Prestige, a lot of it was more of the same.

Aside: Timmons’ performances provide a good illustration of what is often meant by “soul jazz.” The name hints at the origin of the style; it is another of the fruitful crossings of jazz with other African-American musical traditions, in this case gospel, which he learned in his first jobs playing in the church where his grandfather was a minister. It’s also used for crossings of jazz with R&B and blues.

And so this is where we find Timmons in January 1966: in Van Gelder Studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, leading a quartet with Jimmy Cobb on the drums, Ron Carter on bass, and Wayne Shorter on tenor sax. The latter two musicians had just come from a run at the Plugged Nickel with their boss Miles Davis, who had recovered from his hip surgeries and was getting back to the trumpet. Those live concerts, which can be heard on record (but not in my vinyl collection), are by turns tentative, thrilling and explosive, as his band, by silent agreement, played unexpected notes at every turn to challenge Davis into rising to the occasion. There’s none of that here, just solid small-group jazz.

That’s not to say that there’s nothing here for the listener. Timmons’ “Cut Me Loose Charly” and “Damned If I Know” are—on the surface—straightforward enough compositions. But Shorter was nearing his peak as an improvisatory performer in this period, and his work on the first tune is thrilling, taking the straightforward blues-inflected modal melody and breaking it down and building it back up into something strange and new. Carter’s bass work opens the track, bringing some of the same constant pulse that underpinned the most exciting tracks on E.S.P. Then Shorter takes over and pulls the track into a completely different key, picking up the relative major from the opening minor modal blues. When Shorter lays out, the trio continues on but carries some of the momentum from Shorter’s thrilling solo even as some of the improvisation tilts back to a simpler blues.

The opening track is followed by the first recording ever of Shorter’s “Tom Thumb,” which would more notably appear on his own Schizophrenia a year later in a fuller arrangement. Here the tune and soul leanings are intact, as Shorter demonstrates his uncanny ability to incorporate memorable melodies and modal scales into every idiom, even if some of the harmonies aren’t as fat as on the later recording. Timmons’ piano underneath brings flavors of bossa nova and blues, sometimes within the same bar. Shorter plays with rhythm and scales on his solo, sounding looser and freer here than on the opening track. And Jimmy Cobb hangs in, flexing with Timmons from style to style and dropping bombs underneath Shorter’s flights. The track is remarkable and makes me wish that this Shorter composition was covered more frequently.

There follow three Ron Carter compositions. Carter was spotlighted less often as a composer than Shorter and Hancock on the Second Great Quintet recordings, but “Ein Bahn Straße,” “Tenaj,” and “Little Waltz” all prove he was no slouch. The first composition is a jubilant little jitterbug, and Shorter, Carter, Cobb and Timmons sound like they’re having a blast on it. Toward the end, the band falls away and Carter plays a walking bass line solo that pauses, staggers and recovers, suggesting that the listener might not be walking down the one-way street entirely under his own power.

“Ein Bahn Straße” is followed by “Damned if I Know,” which continues the bluesy theme of the other Timmons composition on the album but does not contribute significance in the solos. Carter’s “Tenaj,” on the other hand, is far more interesting, a waltz whose melody climbs and twirls in Shorter’s solo. When Timmons’ turn comes, his solo is more contemplative and lyrical than we’ve heard him so far on the record, and there’s a hint of tenderness, then of steely determination as he shifts meter in the last two minutes of the track. It’s a real standout.

“Little Waltz,” the last of Carter’s compositions, closes the album. It’s what it says on the tin: another three-quarter time song, less momentous than “Janet” but still interesting, in a mode that is strongly reminiscent of his “Mood” from E.S.P. Shorter’s solo recalls that earlier song but is more agitated, pulling away from the waltz feel into something angrier. By contrast, Timmons gives us something that feels like a twisted Vince Guaraldi track, with a reassuring feel even as the modal scale takes us to unusual places.

It’s a fitting end for an unfairly forgotten album, and a good reminder that even jazz that isn’t at the top of the pile repays close listening, especially when Shorter and Carter are aboard. We’ll hear them in more familiar climes next time.

You can listen to the album here: