I’m most of the way through listening to Jane Siberry’s collected works, which she has made available for free download on a “pay it forward” basis. It’s a rare opportunity to listen to an artist’s evolution over a short period of time.

I had only ever heard, really, Siberry’s 1993 album When I Was a Boy, and some of her soundtrack work (“It Can’t Rain All The Time” from The Crow and “Slow Tango” from Faraway, So Close!). I was really, really into When I Was a Boy, to the extent that I forced “Temple” on anyone who would listen, with occasionally embarrassing results. (Okay, so “You call that far? You call that hot? You call that darkness? Well, it’s not” isn’t exactly high poetry.) But some of her songs reach so deep into the psyche, including “Slow Tango,” “Sail Across the Water,” and of course “Calling All Angels,” that I remained in love with the music anyway.

I’m not sure why I never found another one of her albums after that. Maybe it was the typography on the cover of Maria (I’ve never liked that particular script font). Or maybe it was because one album later she was self-releasing her albums and distribution fell off.

Or maybe it was because the two recordings that followed Maria were, respectively, Teenager, an album of modern recordings of songs that she wrote as a teenager, and A Day in the Life, a found-sound recording that followed her through a regular day. I think some artists benefit from editing.

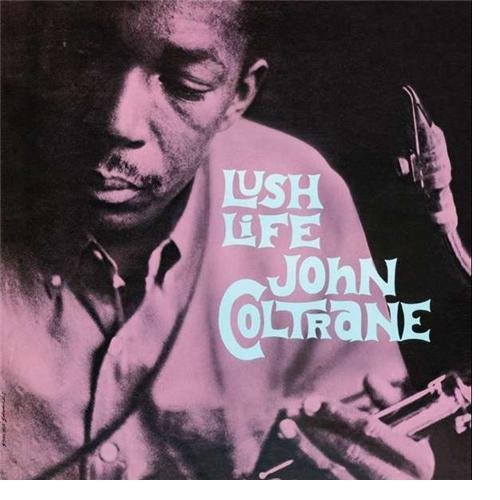

But listening to the whole catalog puts those two albums in perspective. She followed them with a three disc set, New York Trilogy, that went all sorts of unexpected places, like a live band rendition of her trippy “An Angel Stepped Down (And Slowly Looked Around)” that might better the studio recording, a full album of songs about finding one’s own voice, and a moving double album of untraditional Christmas songs. And before When I Was a Boy were some deeply worthwhile albums, including The Walking, which feels like a successor to both Laurie Anderson and Astral Weeks. And Maria? A very cool album of offbeat vocal jazz — though, again, I’m not sure I needed the entirety of the twenty-minute “Oh My My.”

So it’s been quite a gift. Not sure about the best way to “pay it forward,” though, since I don’t have any music of my own to release. Maybe telling you to go download it is the right call. Strongly recommended: The Walking, No Borders Here, When I Was a Boy, Maria, New York Trilogy, and Hush. I’m not done listening yet, so maybe I’ll expand the list.

[audio:http://www.sheeba.ca/MUSIC/m02CY_08_Calling_All_Angels.mp3|titles=Calling All Angels (Choir version, no k.d. lang, from Sheeba.ca)]