Album of the Week, January 3, 2026

There is a danger, with larger-than-life musicians (or really any public figures), that you remember them as caricatures, not for the balance of what made them great but for the quirks that stand them out from the crowd. Such a figure is Charles Mingus, about some of whose albums we’ll write about for the next little bit. Undeniably a genius and a great composer and performer, it’s tempting to remember him for his rages1, for the impenetrability of his performances,2 and for his wild Epicureanism that launched such monuments of excess as his legendary eggnog recipe. As always, the curative is simple: let’s listen.

As I’ve lamented before, the scope of this series of posts about music is limited, by design, to the contents of my vinyl collection. If that were not the case, we might start with a different Mingus recording: Pithecanthropus Erectus, for instance, or certainly his 1959 masterpiece for Columbia Records, Mingus Ah Um. But neither of those records is on my shelf at present, so we’re going to start with a slightly unconventional choice, a record that Mingus made at a time when both Atlantic and Columbia were releasing his albums but that he chose to release on the small Candid Records label, to give a less filtered view of his work.

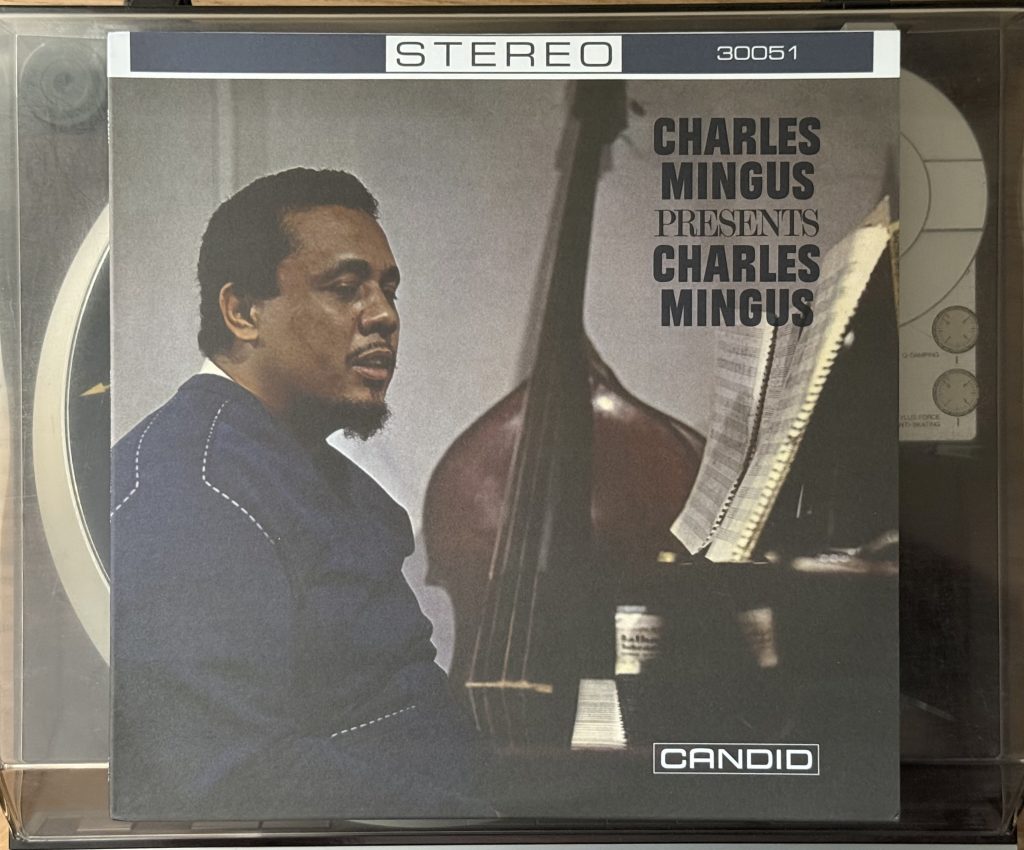

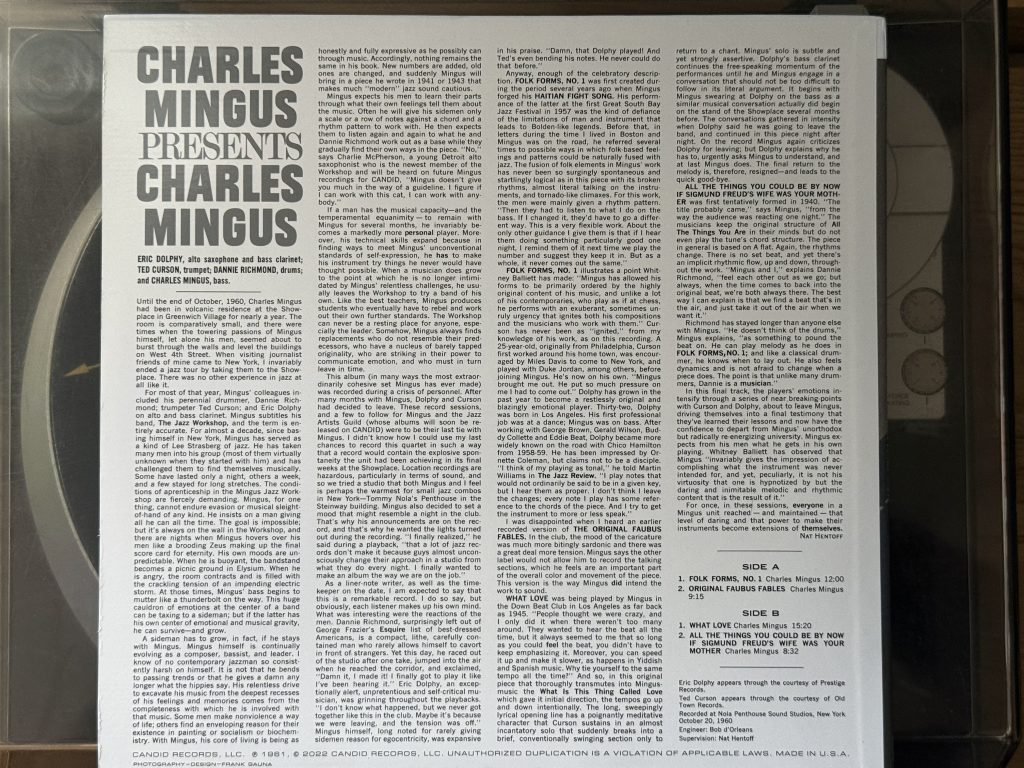

Candid, founded in early 1960 by parent label Cadence Records owner Archie Bleyer, had as its A&R director jazz writer and critic, and civil rights activist, Nat Hentoff. He sought out sounds that, to him, reflected the jazz of the dawning 1960s. The second album the fledgling label released was Max Roach’s milestone civil rights suite We Insist!; Mingus, Roach’s former rhythm section partner in Charlie Parker’s combo, released the fifth album in the series with a pianoless quartet consisting of multi-instrumentalist Eric Dolphy, trumpeter Ted Curson, and drummer Dannie Richmond. Though recorded in the studio in October 1960, Mingus sought to present the illusion that the performance was happening live in a nightclub, going so far as to introduce the first tune with the admonition not to applaud between tracks and to refrain from ordering food and drink during the recording. Generally speaking, his approach to the album (as indicated by the title) was to take control of the way his own music was typically presented to the public.

The first tune is titled “Folk Forms, No. 1;” the “folk form” in question is the blues. Mingus had a complicated relationship with the blues; he was clearly conversant with the form and the feel of the blues, but just as clearly resented the insistent demands that he play more blues and less of his own music.3 However he felt about it, this is a deep blues. Mingus starts the song solo, with a rhythmic figure in the bass that is slightly reminiscent of the opening to his great tune “Better Get Hit In Yo’ Soul.” Richmond follows him, listening to his rhythm and replicating it in snare and hi-hat. Dolphy follows with an essay at the melody, and Ted Curson plays a counterpoint to the melody; the two horns trade ideas and thoughts as though executing a complex fugue, but the lines are all improvised, the group turning on a dime as Mingus proposes different phrases and rhythms in his solos.

“Original Faubus Fables,” a retitling of the 1959 “Fables of Faubus” for contractual reasons, is the most clear case of Mingus presenting his music the way he wanted it to be heard. The original version of the tune had lyrics that were highly critical of Arkansas governor Orval Faubus, who legendarily called out the Arkansas National Guard to prevent Blacks from enrolling in Little Rock High School following the 1957 federally mandated desegregation order. Columbia Records was legendarily cowardly about putting out any records that would offend the Southern buyer, and requested that Mingus present the song as an instrumental; this conflict and others possibly led to Mingus not extending his recording contract with Columbia beyond the two records released in 1959. The lyrics are not exactly epic poetry, but they resonate:

Name me someone who’s ridiculous, Dannie

Governor Faubus!

Why is he so sick and ridiculous?

He won’t permit us in his schools!

Then he’s a fool!Boo! Nazi Fascist supremists!

Boo! Ku Klux Klan (With your Jim Crow plan)Name me a handful that’s ridiculous, Dannie Richmond

Bilbo, Thomas, Faubus, Russel, Rockefeller, Byrd, Eisenhower!

Don Heckman has commented that Mingus doesn’t let his portrait of Faubus give the politician too much power; he keeps the music on a light, satirical level, poking fun at Faubus rather than demonizing him.

“What Love?” is an original composition that approximately combines “You Don’t Know What Love Is” and “What Is This Thing Called Love?” Hentoff’s liner notes position this deep dark ballad as being inspired by a personnel crisis in the band; after many months together, both Dolphy and Curson had decided to move on from Mingus’ band, and Hentoff cites some of the melodic choices in “What Love?” as conversations between the bandleader and his saxophonist, alternately cursing the choice to leave and imploring him to stay. Dolphy plays some far-out music on the bass clarinet in this number in conversation with Mingus’s angry, imploring, and ultimately resigned pizzicato solo.

The final track, “All The Things You Could Be By Now If Sigmund Freud’s Wife Was Your Mother,” is a complete free-for-all, introduced by a complex melody played by both Dolphy and Curson in harmony before the trumpeter takes the first solo, followed by Dolphy, with Richmond banging things out underneath both. This performance shows Mingus at his most far-out. There isn’t much of his genius for melody or harmony here, just him and his three players going flat-out in a wunderkammer of improvisational magic.

Mingus’s many facets as a musician included the ability to collectively improvise with his band at the highest order, and …Presents Charles Mingus is a great example of that. But he might have been even more effective and innovative as a composer of longer works, and we’ll hear one of those next week.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

BONUS: This quartet doesn’t seem to have too many live shows recorded, but an expanded version of the band, adding Booker Ervin on tenor and the amazing Bud Powell on piano, played the Antibes Jazz Festival on July 13, 1960, five days before the quartet entered the studio to record …Presents…. It’s a monster of a live recording; here’s “I’ll Remember April” from the French TV presentation of the concert.

- Mingus was legendarily fired from Duke Ellington’s band in 1953 over a confrontation with trombonist Juan Tizol. Accounts differ as to what happened exactly; Mingus’s autobiography Beneath the Underdog claims Tizol impugned his musical abilities while using the N-word, while other onlookers claim Mingus was insulted when Tizol called him out for flubbing a note. It is pretty clear from all accounts, though, that Mingus rushed after Tizol with either a pipe or a fire axe in his hand. ↩︎

- Mingus premiered his major work Epitaph in 1962 at Town Hall in New York City to mixed reception. Again, accounts differ as to what happened, but poor sound at the venue and a general state of under-rehearsedness on the part of the band appear to have doomed the original performance. The concert was later released on Blue Note Records in the 1990s, when I was first expanding my jazz horizons; I thought it was pretty good. ↩︎

- In the liner notes to his 1960 Atlantic Records session Blues and Roots, Mingus noted, “This record is unusual— it presents only one part of my musical world, the blues. A year ago, Nesuhi Ertegün suggested that I record an entire blues album in the style of ‘Haitian Fight Song,’ because some people, particularly critics, were saying I didn’t swing enough. He wanted to give them a barrage of soul music: churchy, blues, swinging, earthy. I thought it over. I was born swinging and clapped my hands in church as a little boy, but I’ve grown up and I like to do things other than just swing. But blues can do more than just swing. So I agreed.” ↩︎