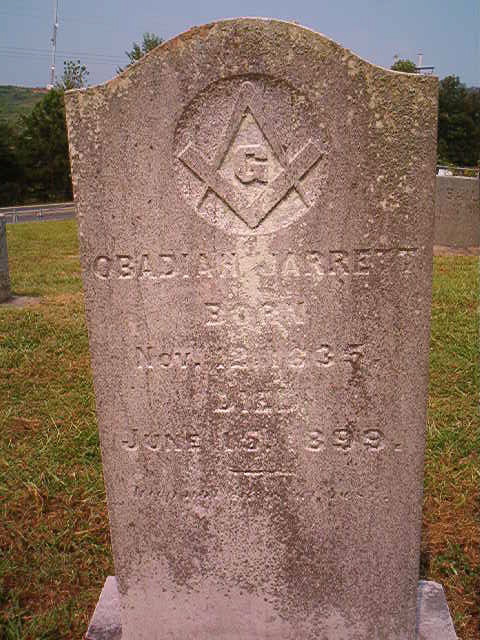

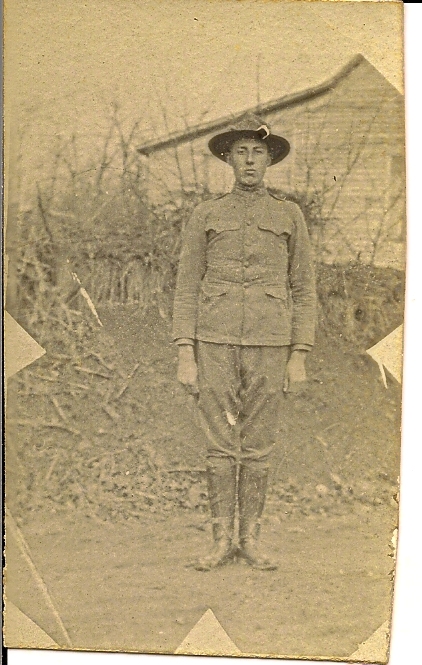

I’ve told the story of my great-great grandfather Obadiah Jarrett during the Civil War, and how he narrowly escaped being shot as a deserter from the Confederate army. On a recent visit to the Freeman Gap Baptist Church Cemetery in Madison County, North Carolina, I was reminded that my grandmother’s side of the family also saw service during the conflict, and with a clear day yielding a good shot of Seth’s tombstone (above), I thought it would be a good time to learn a little about what he had done during the war.

The tombstone provides us with the obvious first clue: Seth served in Company C of the 2nd North Carolina Mounted Infantry—a Union regiment. The Second was formed in Knoxville in the fall of 1863, and Seth was one of several Freeman boys from Buncombe County (none his direct kin, though presumably some were cousins) who enlisted; he joined up on September 26, 1863, at age 18.

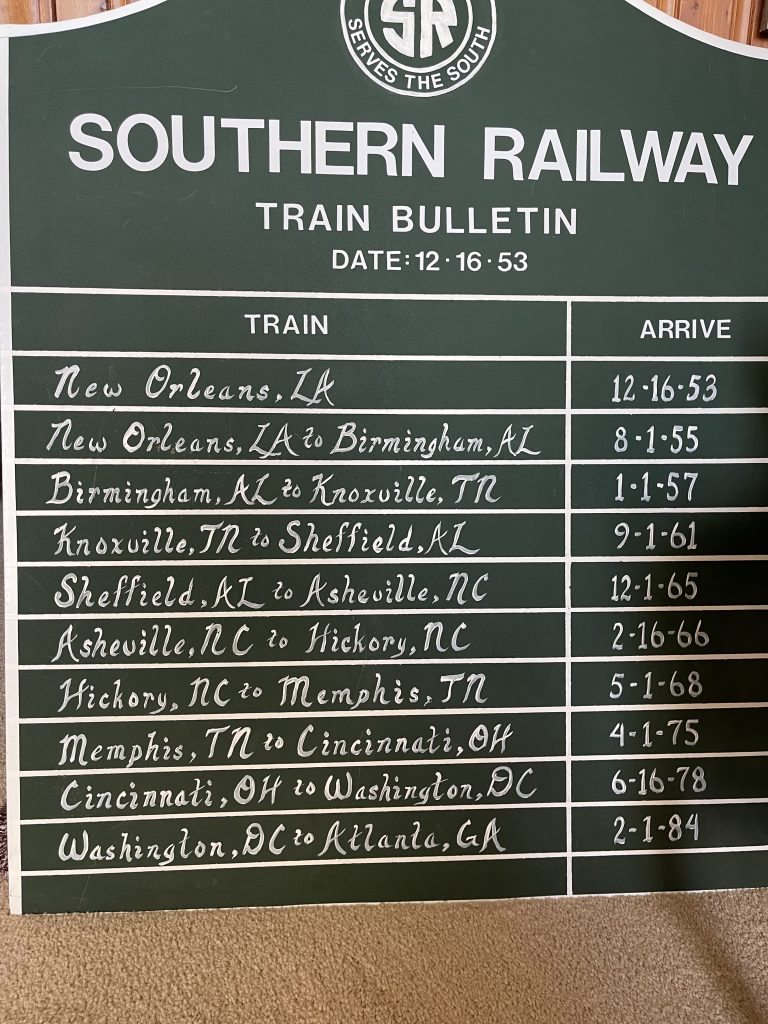

According to National Park Service records, the new regiment was ordered to Greeneville about three weeks after Seth enlisted, then headed to Bull’s Gap before marching across the Clinch Mountains to the Clinch River, where Seth and the regiment saw action at Walker’s Ford on December 2. The regiment then was moved down to Mississippi through February before returning to Cumberland Gap. The regiment moved into Western North Carolina in late March and early April, 1865, and served until August 16, 1865 when the unit was mustered out.

As part of these events, the Second advanced on Asheville, but was unable to take it from the 62nd North Carolina Infantry. They later were directed to Swannanoa Gap, where on May 6, 1865 they encountered a Confederate force led by General Thomas. In the ensuing skirmish, Union soldier James Arwood was killed. This event was recorded as the last battle and last casualty of the Civil War, coming weeks after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

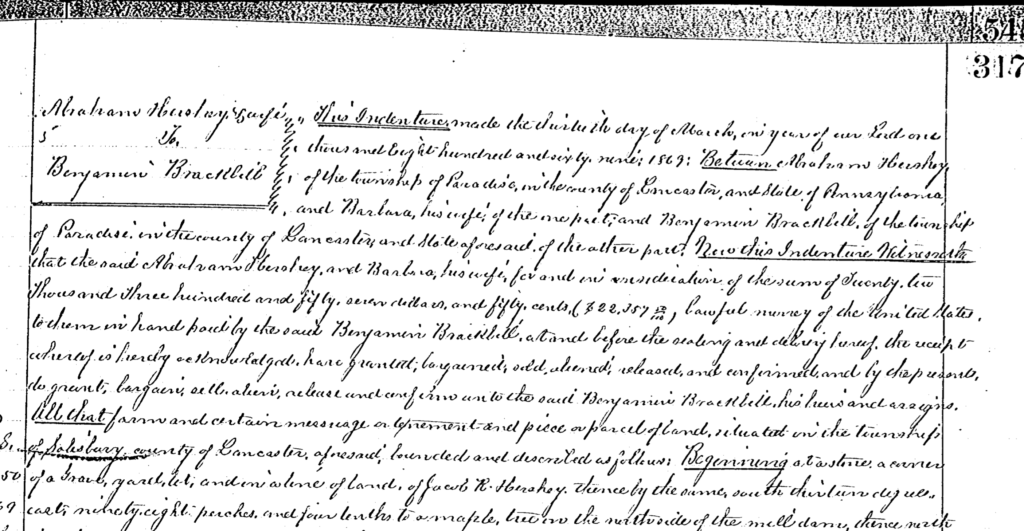

The one event in Seth’s service that has a definitive record of his participation happened in 1864, when Major-General Schofield ordered a detachment of the 2nd to join the 3rd on a mission to make a raid against the enemy and destroy bridges. Due to a classic military clerical error, the men of the detachment were erroneously listed as deserters in the rolls of their regiments. It took until 1869 and an act of Congress to correct the error in their record. I’m going to need to dig a little more into what happened here; an entire detachment being “accidentally” marked as deserters is interesting. (See below for update.)

Seth returned home, married Cyntha (or Syntha or Cynthia) Dent Lunsford in 1866, and died in 1914. It’s said that his faithful dog was so heartbroken when Seth was buried that he dug down into his grave three feet to try to get to the casket.

Update 4/22: The Third North Carolina Mounted Infantry Regiment is an interesting unit. Known as “Kirk’s Raiders” and “bushwackers,” the unit became known for its guerilla tactics. Seth’s records show that he was detached to the Third in June of 1864 and did not rejoin the Second until April 1865. During that time, the unit fought at Bulls Gap and Red Banks in Tennessee, and led Stoneman’s Last Raid.