DevOps Topologies: considering all the ways that development and operations organizations can work together (or separately) and what’s wrong (or right) about each option.

Author: Tim Jarrett

The myth of fingerprints

InfoWorld (Chris Wysopal): Election system hacks: we’re focused on the wrong things. Chris (who cofounded my company Veracode) says that we should stop worrying about attribution:

Most of the headlines about these stories were quick to blame the Russians by name, but few mentioned the “SQL injection” vulnerability. And that’s a problem. Training the spotlight on the “foreign actors” is misguided and, frankly, unproductive. There is a lot of talk about the IP addresses related to the hacks pointing to certain foreign entities. But there is no solid evidence to make this link—attribution is hard and an IP address is not enough to go on.

The story here should be that there was a simple to find and fix vulnerability in a state government election website. Rather than figuring out who’s accountable for the breach, we should be worrying about who is accountable for putting public data at risk. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter who hacked the system because that doesn’t make the vulnerabilities any harder to exploit or the system any safer. The headlines should question why taxpayer money went into building a vulnerable system that shouldn’t have been approved for release in the first place.

I couldn’t agree more. In an otherwise mediocre webinar I delivered in June of 2015 on the OPM breach, I said the following:

After a breach there are a lot of questions the public, boards and other stakeholders ask. How did this happen? Could it have been prevented? What went wrong? And possibly the most focused on – who did this?

It is no surprise that there is such a strong focus on “who”. The media has sensationalized stories about Anonymous and their motives as well as the motives of cyber gangs both domestic and foreign. So, instead of asking the important questions of how can this be prevented, we focus on who the perpetrators may be and why they are stealing data.

It’s not so much about attribution (and retribution)…

…it’s about accepting that attacks can come at any time, from anywhere, and your responsibility is to be prepared to protect against them. If your whole game plan is about retribution rather than protecting records, you might as well just let everyone download the records for free.

So maybe we should stop worrying about which government is responsible for potential election hacking, and start hardening our systems against it. Now. After all, there’s no doubt about it: it’s the myth of fingerprints, but I’ve seen them all, and man, they’re all the same.

It’s not nice to fool Mother Apple

Daring Fireball: Dropbox’s MacOS Security Hack. Gruber rounds up a bunch of links on Dropbox’s bad security practices in its Mac client. Basically, as documented by Phil Stokes, Dropbox asks for your admin password, injects itself into the list of applications that can “control your computer” in the Security & Privacy control panel, and reinjects itself if it’s removed from the list. Thankfully Apple has closed the loophole that allowed this to happen.

The conclusions I take from this:

- Dropbox really wanted to ensure that it could take some action that required Accessibility apps

- Their product manager didn’t trust users to grant the right authorizations and didn’t want to give them the ability to remove the permissions

- Their engineering staff either didn’t push back or got rolled over

- Their security staff either wasn’t consulted or didn’t think that this was dangerous—surely no one would ever find a vulnerability in the Dropbox Mac Client and use it to run unauthorized code? Oh wait.

Their PMs respond: the Accessibility permissions were necessary to integrate with other third party applications, and Apple’s APIs didn’t grant the right level of access.

As they say: Developing…

Smart thermostats, dumb market

One of the things I’ve been theoretically excited about for a while in iOS land is the coming of HomeKit, the infrastructure for an Internet of Things platform for the home that includes standard controller UI and orchestration of things like smart thermostats, light bulbs, garage door openers, blinds, and other stuff.

I’ve been personally and professionally skeptical of IoT for a while now. The combination of bad UX, poor software engineering, limited upgradeability, and tight time to market smells like an opportunity for a security armageddon. And in fact, a research paper from my company, Veracode, suggests just that.

So my excitement over HomeKit has less to do with tech enthusiast wackiness and more to do with the introduction of a well thought out, well engineered platform for viewing and controlling HomeKit, that hopefully removes some of the opportunities for security stupidity.

But now the moment of truth arrives. We have a cheap thermostat that’s been slowly failing – currently it doesn’t recognize that it has new batteries in it, for instance. It only controls the heating system, so we have a few more weeks to do something about it. And I thought, the time is ripe. Let’s get a HomeKit-enabled thermostat to replace it.

But the market of HomeKit enabled thermostats isn’t very good yet. A review of top smart thermostat models suggests that Nest (which doesn’t support HomeKit and sends all your data to Google) is the best option by far. The next best option is the ecobee3, which does support HomeKit but which is $249. And the real kicker is that to work effectively, both require a C (powered) wire in the wall, which we don’t have, and an always on HomeKit controller in the house, like a fourth generation Apple TV, to perform time-based adjustments to the system.

So it looks like I’ll be investing in a cheap thermostat replacement this time, but laying the groundwork for a future system once we have a little more cash. I wanted to start working on the next-gen AppleTV soon anyway. Of course, to get that, I have to have an HDMI enabled receiver…

Cocktail Friday: Frank of America

For today’s Cocktail Friday, we’re taking a look at one of my favorite drink categories: cocktails that riff on whiskey plus herbal flavors. There are at least two major families, the Manhattan (rye or bourbon and vermouth plus bitters) and the Boulevardier (rye or bourbon and vermouth plus Campari).

The combination of the fiery and sweet in bourbon or rye set up nicely against the bitterness and herbal characteristics of bitters or amari (the general category in which Campari fits). The nice thing is that there are literally dozens of kinds of bitters and possibly hundreds of kinds of amari out there, and most of them are pretty different from each other because they each use proprietary blends of herbs and spices. So there are lots of ways you can make unique (if subtly different) drinks that follow this general recipe.

Such is today’s cocktail, the Frank of America. Published in the New York Times by Robert Simonson, the cocktail originated in The Bennett in New York City and is named after the bar director’s boyfriend, named Frank, who works at Bank of America. It calls for rye, Byrrh (a slightly more bitter vermouth analog), Amaro Abano (a strongly herbal, slightly peppery amaro), Angostura bitters, and maple syrup, with an orange twist. I didn’t have Amaro Abano so I substituted Averna, which is slightly less herbal and more spicy; I used bonded Rittenhouse Rye for the whiskey component. The result was a little sweet but amazingly complex and herbal. Apparently the original uses a spiced maple syrup; that might address the sweetness. But it’s definitely worth a drink if you have this stuff in your cupboard.

Or experiment with other amari, vermouth or vermouth-like drinks, and whiskeys. There’s a lot of directions that a little experiment can take you.

As always, here’s the Highball recipe card, if you plan to try it out. Enjoy!

Recovering passcodes from iPhone 5c without a backdoor

Bruce Schneier: Recovering an iPhone 5c Passcode. Remember when the FBI insisted that Apple needed to backdoor iOS because otherwise recovering the passcode and accessing the phone of the San Bernardino killer was completely impossible? Good times.

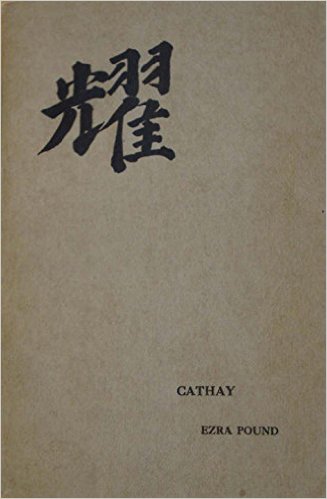

Pound: Cathay

There are some poems that I feel I’ve known forever and yet never fully appreciated. Such was “The River Merchant’s Wife,” one of fourteen poems that Ezra Pound “transcreated” from the Chinese in his 1915 collection Cathay. Knowing a debatable but at best small amount of Chinese, Pound relied on notes and translations prepared by Harvard scholar Ernest Fenollosa to create the poems within.

I found this centennial edition of the work, which restores “The Seafarer”(which unlike all the other poems was translated from the Old English) to the collection, in the Bookstore in Lenox this summer. It’s a fantastic edition, not only because of the poetry (which remains among my favorite of Pound’s works) but because the edition also provides Fenollosa’s notes, with fresh translations of the Chinese characters.

The edition is valuable for a couple of reasons. First, it provides clarity on some of the controversial “mistranslations” of the works. In some cases, Pound was led astray by Fenollosa’s translation, but in others he set Fenollosa’s mistranslations aside and got to the heart of the emotion or image in the original Chinese poem.

Second, it gives a powerful argument for the importance of diction, in the sense of “choice and use of words and phrases in writing.” Fenollosa’s literal (mis)translations feel clumsy and heavy on the page. Pound cut them down to the bone and recreated them into art.

The Trap of ‘First’

Keith Houston, I Love Typography: The Prints and the Pauper. Otherwise sound history of printing that falls into the classic rhetorical trap: can we call Johannes Gutenberg the “father” of printing despite the fact that he didn’t invent movable type?

This is the same sort of rhetorical trap that lots of otherwise smart people in technology fall into all the time. I call it the Trap of ‘First’: the assumption that just because you are first to think of, or even implement, something, you should get special credit and deserve special success.

I should know about the Trap of ‘First’, as I was a longtime victim of it. For years I believed, like many Apple fans, that the slew of inventions that came out of Apple during the late 1980s and early 1990s made them more deserving of market success than Microsoft. “But they did it first!” I’d howl: about window based operating systems, computer video, smooth on-screen type, really anything you can imagine.

What I’ve come to understand is that there’s as much value generated in innovating on someone’s solution than in (merely) inventing it in the first place. Look at the iPod. There were certainly other MP3 players on the market. But the unique combination of great UI and (most importantly) the iTunes Store made the iPod the first one that really filled the customer’s need.

Houston points out that early Chinese innovations in printing preceded Gutenberg by hundreds of years. He correctly also points out that they were unwieldy (requiring over 60,000 unique woodblocks), produced poorly legible pages (thanks to the water-based Chinese calligraphic ink that didn’t adhere well to the woodblocks), and generally uneconomical (only printing on one side of the page thanks to the delicate Chinese paper; woodblocks had to be cut by hand rather than cast from reusable metal molds).

Gutenberg’s press, incorporating innovations not only in movable type but also in creating methods to mass produce it and create legible pages with it, was not the first, but I’d argue that is beside the point. The point is not to be first, but to solve enough of the problem that your solution is worthwhile. Hence why “first mover advantage” … often isn’t.

Mid-year resolution check-in

At the end of last year, I made a resolution that I was going to start writing on my blog again, after several years of intermittent posts. It’s almost three-quarters of the way through the year, so now seems like a good opportunity to take stock of how I’m doing.

Motivations

First, I note that the original post didn’t really specify all the reasons that I’m doing this. It’s worth noting now for posterity. Here’s why I made the resolution:

- A desire to get my writing back out of siloed Internet presences like Facebook and Twitter. I mentioned this in the original post. I don’t have anything against those platforms and still use both, but I don’t want my best work to only live there. I want some control over what happens to it.

- A desire to improve the ease and fluency of my writing. My job now requires a fair amount of written, world-facing communication in a way that it didn’t before. If I’ve learned anything in my life, it’s that everything you can do well is like a muscle that gets more powerful with exercise, and writing is no exception.

- A more general feeling of dissatisfaction. This was only apparent to me in retrospect. At the end of last year I wasn’t happy with some things in my life, and in the past writing has been a good mechanism to start taking control.

Outcome

So, how’s it gone? Answer: pretty well quantitatively, and very well qualitatively.

Quantitatively: My goal was to write something every week day. January started strong: I only missed one week day and had an extra Saturday post, so we’ll count that as a win. February missed one day, as did March. But two days missed out of 65 is still a 97%.

April was perfect. But May missed two, and June… ah. June missed six. So that’s an 87% for the second quarter. Not so good. July missed six again, and August missed five. So my overall score was an 88%. Kind of underwhelming from a perspective of hitting perfection. However, putting it in perspective, in all of 2015 I wrote nine posts total, and three of them were in the last two days of the year. So getting to 88% (so far) is a huge upswing.

Qualitatively: I’m actually really proud of some of the writing I’ve done on the blog in the last year to date. I had people in the TFC come up to me and talk to me about what Sunday’s post about the Transmigration meant to them, which has never happened. It’s probably the best thing I’ve written in a while. But there have been other good posts and series, including the song-by-song reviews of A Moon Shaped Pool; a set of Virginia Glee Club discoveries including the identification of its first black member, the early history of Wafna, Founders Days through the years, and a pocket history of the contest that led to the writing of “Virginia, Hail, All Hail”; obituaries for David Bowie, Andy Grove, Johan Botha and Reilly Lewis; and some one-offs about “Eighty-One,” mononucleosis, Asheville barbecue, Tomorrowland, the Shelton Laurel massacre, and trade shows. There have also been Random Fives, cocktails, and lengthy writing about ripping vinyl. That’s OK. As someone once wrote about Sylvia Plath, if she couldn’t make a table out of a poem she was working on, she was more than happy to make a chair. Meaning: writing is writing, and not everything has to hit it out of the ballpark, but you need to keep approaching the craft all the time.

I think I’m proudest of a set of posts I’ve made about race relations and the legacy of slavery, a topic I had never engaged with in the past and that I needed to engage and process. The series so far includes:

- On not forgetting

- The machinery of slavery

- Ride the Chariot and Yale: a study in misattribution

- Lexington, Massachusetts and the Underground Railroad

- “Well, God is in his heaven, and we all want what’s his…”

- Out of the background: James Armistead Lafayette

- “…and let some of the bruise blood come out to show them”

- Separating the artist from the art

- At home in The Mews

- Slavery on the Lawn: follow up

That’s not a bad body of work for not quite nine months. I’m pretty pleased with how this has gone so far. Now to figure out what the next turn of the screw is.

Light reading

The Congressional report on the OPM breach is available. More than 200 pages of non-searchable PDF. Set aside some time for a little light reading.

Memorial Hall, Harvard University

It was an unusual treat to spend so much time in Memorial Hall and Sanders Theater this week. The high Gothic style of the building and the sombreness of the memorial hall proper was a good preparation for the work we were there to sing.

I posted an album of my favorite photos of Memorial Hall to Flickr.

Transmigrating

Seven years ago today, I summed up the things that happened eight years ago before that: the small amount that I could write, stunned, on September 11, 2001; my more elaborate write-up from 2002 and, after singing in the Rolling Requiem, my detailed recollections from the day; my thoughts from 2003, on the brink of invasions; my thoughts from 2008, in which I assert that in spite of the attack, we’re still here.

All of which is to say I thought I had processed and finished my grieving for the victims of that bright fall day fifteen years ago.

Then, one night this week after rehearsing Adams’ On the Transmigration of Souls, I attempted to describe Doug Ketcham to one of my TFC colleagues. And I could not speak. I was suddenly dumbstruck by the immense unfairness of what happened to him: twenty-seven years old, a rising star at Cantor Fitzgerald, who retained enough presence of mind to call his parents from underneath his desk after the first plane hit the towers to tell them that he loved them.

Doug was an acquaintance who I wish I had known well enough to call friend. Other UVa friends, like Tin Man, knew him much better. But he was a decent human being who never blinked an eye when I joined the crew that hung around with him. He made you feel less alone.

I spent some time thinking about him in our final rehearsal of Transmigration on Friday. I thought about the fact that I haven’t come to terms with his death after all these years. I thought about the fact that this anniversary still has the power to turn me somber and sour.

And then I thought about the structure of the piece. It opens with street sounds, footsteps, and then the words “missing… missing…” and the reading of names. The choir and orchestra slowly emerge from shifting tonalities to sing words, not of high poesy, but from the families of the victims, who posted them on fliers around the site of the Twin Towers in the weeks after the attack. Everyday words. “…he was tall, extremely good-looking, and girls never talked to me when he was around.” (Which could have been written about Doug.) Or the words of one woman: “I loved him from the start…. I wanted to dig him out. I know just where he is.”

It is at this moment that the orchestra gives a tremendous wrench, building in intensity and volume until at the top of the crescendo the chorus bursts into the moment of transfiguration: “Light! Light! Light!”

But after the transfiguration moment, the chorus drops away, the instrumentation drops back down, and you can hear that the voices and names are still speaking. And so it goes until the end of the work, with a final wordless tone cluster from the chorus yielding to a slendering thread of string sound, which after the thirty minutes of the piece finally resolves upward into a new major key—but not triumphantly, but so quietly it can almost not be heard.

And I think about this ending, and I think I finally understand what Adams was trying to get at. The dead are still with us after the transmigration because they always will be. It is we who must be transmigrated, who must allow ourselves to be changed, to not continue to stand, breath held, on the edge of that dreadful day. We who must resolve upward.

Ripping off the bandaid

Daring Fireball: “Courage.” John Gruber takes a run at the other side of the argument for removing headphone jacks from the iPhone 7 and 7 Plus. Basically, the argument boils down to this: no one is outraged that the future isn’t coming fast enough. As Gruber says:

When we think of controversial decisions, we tend to think of both sides as creating controversy. Choose A and the B proponents will be angry; choose B and the A proponents will be angry. But when it comes to controversial change of the status quo, it’s not like that. Only the people who are opposed to the change get outraged. Leave things as they are and there is no controversy. The people who aren’t outraged by the potential change are generally ambivalent about it, not in a fervor for it. Strong feelings against change on one side, and widespread ambivalence on the other. That’s why the status quo is generally so slow to change, in fields ranging from politics to technology.

Whether you like change or not, it’s important to recognize that there may be benefits that you will forgo by avoiding change. This is any technology product manager’s dilemma: when do the potential benefits justify taking a stand and being an advocate, against the outrage of the proponents of status quo?

I have run into this a lot with big decisions and small. One common version of this is browser support. In enterprise applications it’s historically been a big deal to end support for older browsers. Enterprises like their old technology, because it works just fine, performs its business function, and carries a cost to replace. Unfortunately, that was especially true for web applications that only worked in various versions of Internet Explorer. Thankfully, the industry as a whole got enough courage in the last few years to stand up and advocate for a future in which coddling a poorly behaved, insecure browser with no support for modern standards would no longer be necessary, which makes taking a stand as an individual easier. But when you’re the only one taking the stand it becomes harder.

Me? When I go to iPhone 7, I’ll be using the Lightning to audio jack adapter that comes in the box. I have a nice pair of B&W P3s that I’m not ready to replace yet. But I’ll be looking at wireless headphones the next time I am.

Bitter yourself

Make: John Edgar Park’s Ultimate Bitters Recipe. I’m feeling pretty flush with the success of various attempts at “make your own pickles” (details soon). Maybe “make my own bitters” is next? Certainly could find many worse guides into this realm than JP.

Friday Random 5: Welcome to the terrordome

By special request, I bring the Random 5 back this week. Let’s see what craziness this weekend begins with.

The Cure, “Sinking”: In middle and high school I was aware of the kids who loved the Cure, but never became one until Disintegration came out. When I finally listened to The Head on the Door, I liked it fine, but I found it facile compared to the later effort. The highs were giddy, but the lows felt shallow when stacked up against the massive thundering tracks of “Disintegration.” I still feel that way about songs like “Sinking.” Robert Smith is trying to reach for that note of despair, and for most of the song he doesn’t get there—maybe it’s the keyboards that don’t work for me. But then there’s that bridge: “So I trick myself/Like everybody else/I crouch in fear and wait/I’ll never feel again/If only I could remember/Anything at all.” And then I feel the connection to the dark heart that the best Cure tracks touch.

Herbert von Karajan/Vienna Philharmonic, “Brahms: Ein Deutsches Requiem. I. “Selig sind, die da Leid tragen”: One choral masterwork that has become completely embedded in my soul. This recording doesn’t draw out the precision of some of the interior orchestral lines the way that Levine was able to on his recording with the BSO (on which I sang), but the way that the choir emerges from the void in the beginning, completely seamlessly, with all voice parts completely seamlessly blended is something to hear.

White Stripes, “Why Can’t You Be Nicer to Me?”: Back when the White Stripes were refreshing because of their relative lack of pretense and you weren’t sure whether they were brother/sister, husband/wife, or both, or what.

White Stripes, “I’m Bound to Pack It Up”: Proof once again that the iPhone’s random is really random, this second track from De Stijl sounds like the bastard child of “Going to California” and “We Are Going to Be Friends.”

Patrick Watson, “Big Bird in a Small Cage”: Ever run across a track that you’re not sure how it got into your music library? That’s this track. Wikipedia tells me it was a Starbucks Pick of the Week in 2009, which is probably where I got it—and the last time I heard it. But I like it. Sort of Devendra Banhart meets the Beach Boys and Dolly Parton.