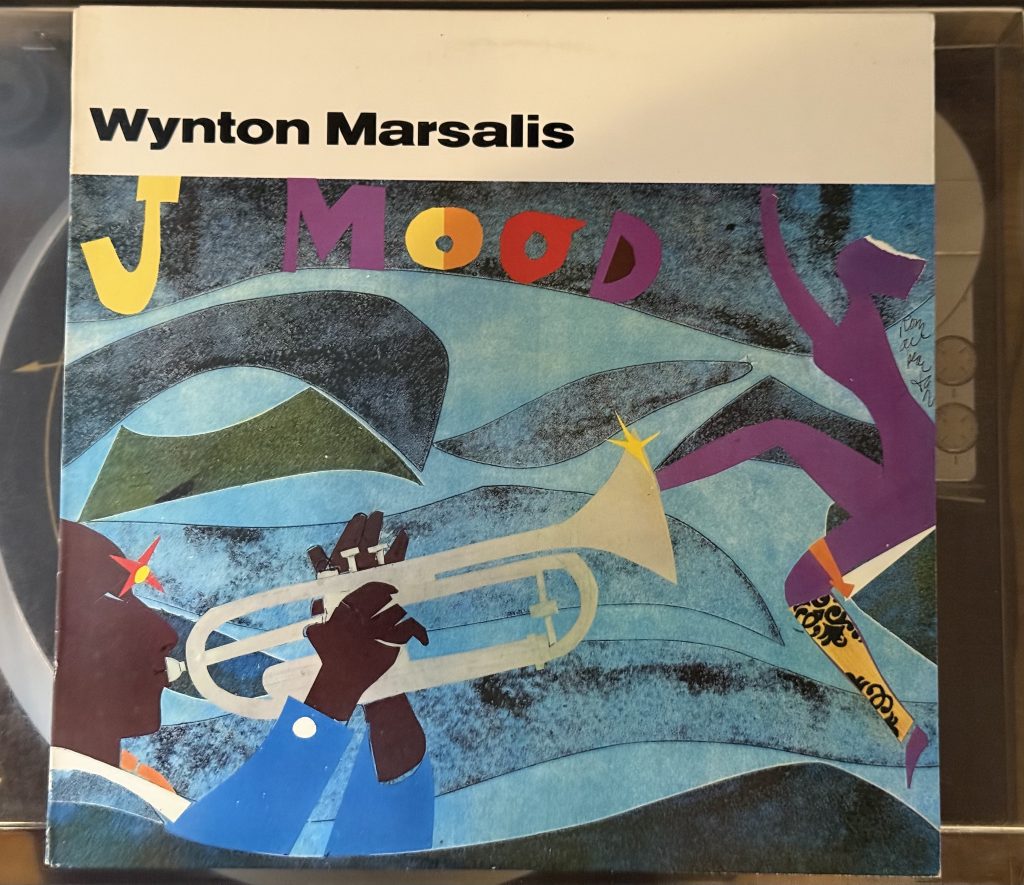

Album of the Week, April 12, 2025

In the Bring on the Night documentary, there’s a brief interview with Kenny Kirkland at the very beginning in which he says, “I’m sure some people, some purists, jazz people, don’t like the idea of our doing this,” meaning being a jazz musician and playing with Sting. Kirkland was sure, all right; his former boss, Wynton Marsalis, had in fact kicked him and his brother Branford out of his quintet for joining Sting’s band. We’ve now heard some of the story about what happened next for Kirkland, but what about Wynton? Interestingly, the answer seems to be that he found his own voice.

One notable thing about Marsalis’s Black Codes (From the Underground) is the degree to which it resembles an album from Miles Davis’s Second Great Quintet. That album was recorded in January 1985. His second album from that year, recorded in December, was a quartet with two new players: Marcus Roberts on piano and Robert Hurst on bass (Jeff “Tain” Watts returned from the old band). Both players would have a noticeable impact on Marsalis’s sound, but the biggest factor was Roberts.

Marthaniel Roberts, who goes professionally by Marcus, was born in 1963, two years after Wynton, to a longshoreman father and a gospel singing mother who went blind as a teenager. It ran in the family; by age 5, Roberts was blind from a combination of glaucoma and cataracts. Also at age 5, he learned to play piano, teaching himself on an instrument at their church. He attended the Florida School for the Deaf and Blind, which had previously graduated Ray Charles, and studied piano formally beginning at age 12. This album was his first recording, and the style that he brought to Wynton’s band, anchored in gospel and ragtime rather than the post-bop influences that informed Kirkland, made a significant impact on Wynton’s sound.

The album opens with “J Mood,” which true to its name seems more like a mood—specifically, a blue mood—than a composition. Starting around this time, Marsalis’s compositions started to feature complex chord changes that could be downright Ellingtonesque, and this one is no exception; there’s also a thread of restraint, as though the music was moving in some mysterious underworld. The meter is complex, too, swerving from a slow 7/4 to bits of 4/4. The band starts out stating the theme together, with the trumpet playing over top of the changes in the piano, and Marsalis goes into a slow 4/4 blues in which he establishes a series of melodic phrases that don’t quite cohere to an actual melody. Tain and Bob Hurst anchor the low end, with Hurst keeping a “walking bass line” feel in his melodic progression but constantly swinging against the beat, and Tain exploding the harmonic envelope with inventive use of cymbals both soft and loud. When Roberts plays, it’s in a deceptively slow cadence that brings some melodic sense to the music, with hints of church in some of the low chords and his arpeggiated right hand, all the while swinging hard. The band finishes where they begin, with only a diminished seventh in the upper octave hinting at any of the development that has taken place.

Marcus Roberts’ sole compositional credit on the album, “Presence That Lament Brings” has a melody, but not an easy one (I am reminded a little of some of the twelve-tone solo lines in Bernstein’s Kaddish) and plenty of rubato to go around. Wynton is muted here, but the effect is less explicitly Milesian than on Black Codes; he seems to be finding his own expression and sound in which the combination of the soft tone of the mute and the growling of his note-bending playing combine to create a completely different emotional space. Space is the defining characteristic of Roberts’ solo, which has both that same deceptively unhurriedness and a sparser chord voicing than on “J Mood.”

“Insane Asylum,” composed by Donald Brown (who was the pianist in Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers when Wynton was in the group), has a lazy intensity about it; there’s still that mute and that extreme swing that seems to wait until the last possible moment to move, and the melody descends chromatically like a swoon. Still, Tain’s cymbal work keeps insistently nudging us forward, and Wynton’s trumpet climbs to the highest heights as if urging us forward up a trail. The tune itself seems to circle back insistently to the the same chromatic descending motif over and over again, as if painfully fixated on it.

“Skain’s Domain” refers to Wynton’s childhood nickname; while you practically can’t refer to Jeff Watts without his rhyming “Tain,” “Skain” seems to be used principally only inside Wynton’s band, and mostly as a joke. The liner notes takes some pains to tell us that “the song is twenty seven bars long, with a two/four measure at the nineteenth bar.” What is true is that the playing is brisk and light enough that you don’t count the measures; though the tune, like everything else, keeps to the minor-key side of the equation, it feels almost sprightly. By contrast, “Melodique” is, rhythmically, a slow blues over a samba rhythm, and bears more than a family resemblance to Herbie Hancock’s “Mimosa.” It plays some of the same tricks with rhythmic pulse and stasis, with the added trick of a twelve-tone inspired melody from Wynton over the top. It’s a gorgeous track, regardless.

“After” is a wistful ballad by Wynton’s father Ellis Marsalis, albeit one that is amped up by Tain’s cymbal work, which urges the track along with splashes, washes, and marches of cymbal sound against the more meditative backing of the piano and the bass. It seems to capture a tender moment alone, where “Much Later” seems to find the couple jitterbugging the night away. The pulse is constantly moving eighth notes, Tain finding a way to swing even at high velocity. The track has a much looser feel, and the cough or sneeze at around the 40-second mark as well as the barely detectable fade-in suggest that it was a full band jam session during which the engineer just happened to be rolling tape. It sounds great and blows some of the sleepiness away, ending the album on a high note—as well as a simultaneous Wynton and Roberts quote of “If I Were a Bell”!

Marsalis was finding his way to the key ingredients of his compositional and performative voice: in addition to the bell-like tone of his early recordings, we get a variety of distinctive sounds through the mute here, along with a healthy dose of both Ellington and Armstrong—as well as the blues. On later albums of his own material for small group, Wynton would lean more heavily into one or another of these directions, particularly the blues—his trio of albums in the “Soul Gestures in Southern Blue” series is worth seeking out—but they play as elaborations of the musical language that was first captured here.

If Wynton was driving deeper into the jazz tradition, he wasn’t the only Marsalis brother to be recording jazz albums. About six months after the quartet wrapped up its sessions for the album in December 1985, Branford recorded his own set and second album, Royal Garden Blues, in New York. But Branford was also busy with some decidedly non-traditional endeavors, and we’ll pick up that story next time.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

2 thoughts on “Wynton Marsalis, J Mood”