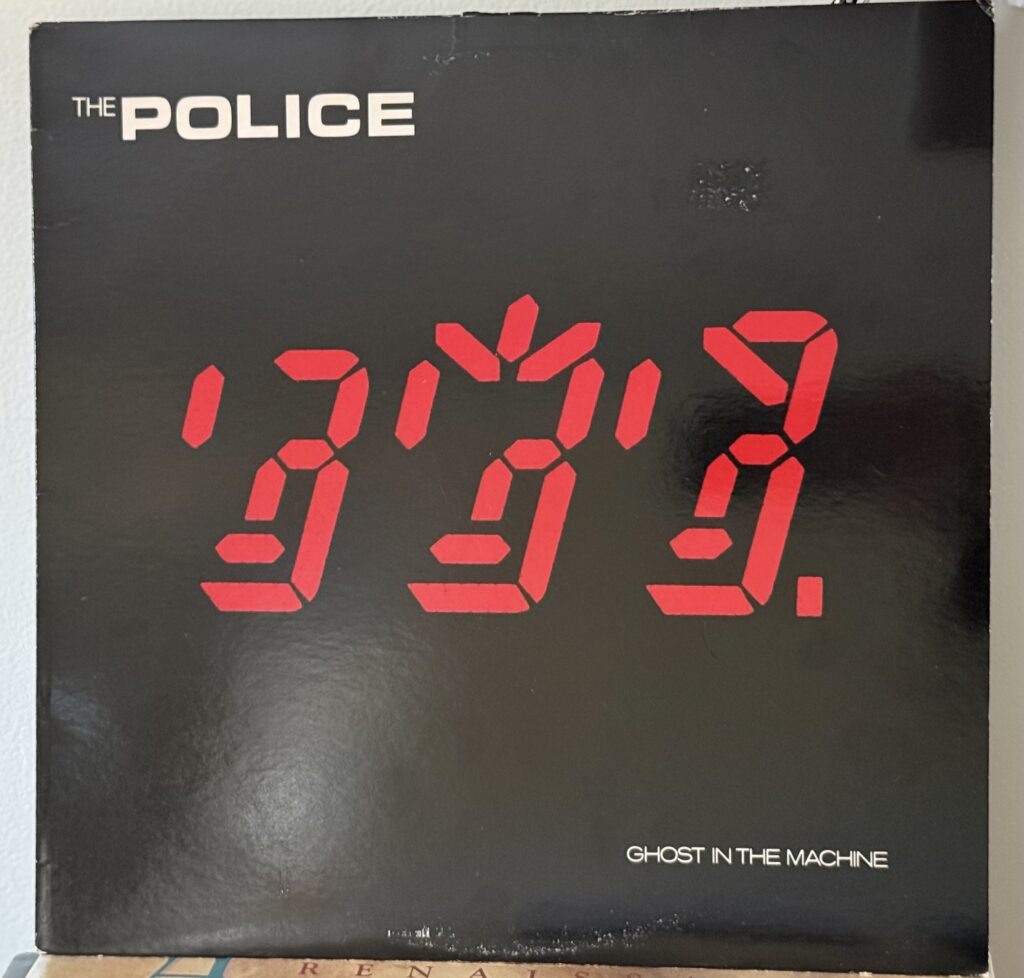

Album of the Week, January 25, 2025

He had been writing the song for five years; it predated the Police. “Every Little Thing She Does is Magic” had been written while Sting, Andy Summers and Stewart Copeland were all members of Strontium 90 with Mike Howlett from the psychedelic rock band Gong. Sting recorded it as a four track demo in a loft in Howlett’s home, playing acoustic guitar and bass. He took it to the band early in their career, who objected that the song was “soft”; he said, “no, look, this is a hit.” He was right, of course.

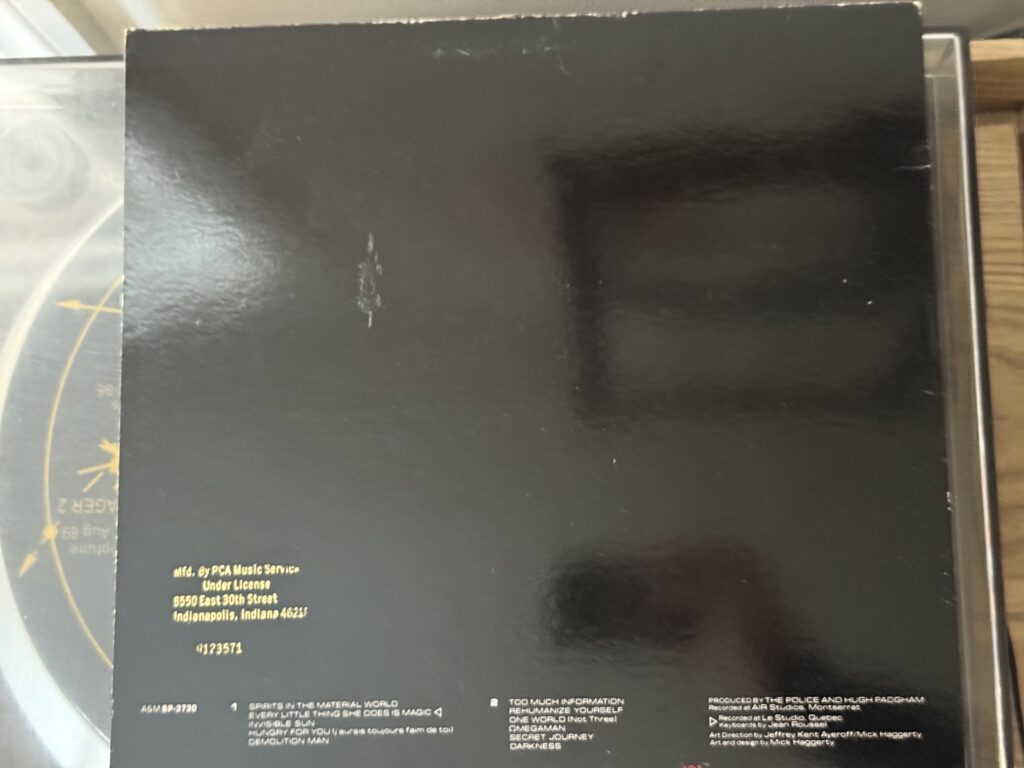

Sting’s “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic” became the second of the “strong three” opening songs on their 1981 album Ghost in the Machine, following the same programmatic approach as they had previously employed on Zenyatta Mondatta. (Tip, kids: starting an album with three strong songs is the way.) The lead-off, “Spirits in the Material World,” sets up the album and “Every Little Thing” is followed by lead single “Invisible Sun.” Both the other two songs continue the theme of dissatisfaction with the realities of the world, this time writing about dictatorial leaders and continual war.

For such strong lyrical content, the album was recorded in an idyllic place. AIR Studios was in Montserrat in the British Caribbean, a residential studio where the band could live as well as record. They were joined by producer Hugh Padgham instead of their prior producer Nigel Gray; Padgham was notable for helping to invent the “gated reverb” drum sound that became a staple of 1980s rock while recording Peter Gabriel’s third solo album with Phil Collins (later perfected on Collins’ first solo album); he had been producing albums for Collins and Genesis (Abacab), helping them get more of a “pop” sound. As the Police began shifting away from their raw trio sound of the earlier records, Padgham’s experience was helpful, even if not completely welcomed by Copeland and Summers. Copeland recalls, “I was getting disappointed in the musical direction… With the horns and synths coming in, the fantastic raw-trio feel—all the really creative and dynamic stuff—was being lost. We were ending up backing a singer doing his pop songs.”

The first sound you hear on the album (after a brisk drum hit from Copeland), in the opening to “Spirits in the Material World,” underscores Stewart’s point. The Police had kept to guitar, bass and drums during their first three albums, but here the hook is played prominently on a Casio keyboard. Sting claims to have accidentally written the hook while messing about with a Casiotone “while I was riding around in the back of a truck somewhere.” Sting liked the synthesizer sound so much that he wanted to record the song without guitar; after much arguing with Summers, they compromised and the lead is played by both guitar and synthesizer, albeit with the guitar buried in the mix. Copeland’s drumming is jaw-dropping here, especially considering the tricky rhythm, shifting from a syncopated four in the verse with no clear downbeat to a clearer backbeat in the chorus.

I should also say a word here about the lyrics. I neglected last week to note the most remarkable thing about “Don’t Stand So Close to Me,” the offhand reference to Vladimir Nabokov in the last verse. If the slant rhyme of “shake and cough” with “Nabokov” and the casual introduction of a parallel to Lolita stands as the principal reminder in Sting’s songwriting that he was an English teacher,1 the reference in this song to the philosophy of Arthur Koestler’s 1967 book The Ghost in the Machine must stand as a close second.

“Every Little Thing She Does is Magic” also has non-traditional instrumentation. While the other keyboard parts on the album are played by the Police (according to various sources, even Stewart Copeland was programming and playing synth parts), the piano on this track was played by session musician Jean Roussel. Originally recruited by Sting to play on the second demo for the song, recorded in Le Studio in Morin Heights, Quebec, Roussel’s piano part from the demo survives on the final track; the band was unable to better his part in AIR Studios, and they simply played over the demo. To be clear: it’s a great song, singable but musically deep, featuring a tension between D minor and D major and a memorable lydian scale in the bass line. It also features one of Sting’s great lyrics: “Do I have to tell the story / of a thousand rainy days since we first met? / It’s a big enough umbrella / But it’s always me that ends up getting wet.” (It should be noted that Ghost was recorded while Sting was separating from his first wife, Frances Tomelty, following the birth of their second child.)

If “Every Little Thing” is poppy and personal, “Invisible Sun” returns to the world of Zenyatta Mondatta for its inspiration. Sting had become a tax exile living in Galway in 1982, and strongly felt the psychological impact of the ongoing troubles in Belfast. He wrote the song about the persistence of the everyday people who lived through the hunger strikes and bombings, feeling that there had to be a light at the end of the tunnel to give them hope. For Stewart Copeland, the “invisible sun” also shone on Beirut, where he had grown up thanks to his father’s travels in the CIA; he accordingly also felt the song in a deeply personal way. Sting refers in the opening lines to “looking down the barrel of an ArmaLite,” the rifle used by paramilitary organizations including the Provisional Irish Republican Army. The song’s subject matter, reinforced by its video showing clips from the Irish conflict, led to its being banned by the BBC, a first for the Police. It would not be the last time Sting wrote about war and its horrors, but it was the first time such a song took the Police to almost the top of the UK charts (it stalled at Number Two the week of September 27, behind “Prince Charming” by Adam and the Ants. Welcome to 1981).

After the powerful one-two-three punch of the opening comes a different kind of run, unusual for a Police album. Where previously there would have been a left turn into something goofy, maybe with a Stewart Copeland song, on Ghost there’s another three-song run by Sting that takes us through the end of the A side and into the B, and introduces another new instrument. I don’t know at what point Sting picked up the tenor saxophone and decided that he needed to play it on Police records, but here he was on “Hungry for You (J’aurais toujours faim de toi),” playing a persistent (and slightly flat) hook — and singing in French. Almost the entire song is in French, except for the final chorus. And it’s horny. Apparently Tomelty’s best friend, Trudie Styler, helped with the translation into French as well as the circumstances of the composition; it was during this time that Sting started a torrid affair with her (spoiler: they got married in 1992 and are still married today). The song itself is slightly overwhelming in its instrumentation; the band appears to have thrown everything at the composition.

“Demolition Man” is similarly rich, but it started life during the Zenyatta Mondatta sessions. Written in the summer of 1980 while Sting was living at Peter O’Toole’s house in Connemara, Ireland, the song wasn’t used for Zenyatta, and Sting ended up offering it to Grace Jones, who recorded it for her 1981 album Nightclubbing. When the Police heard their version, they were inspired to re-record it, or as Andy Summers puts it, “Sh*t, we can do it much better than that.” Summers, indeed, is the hero of the song. If he spent most of his time playing in a relatively restrained way on Ghost, here he is unleashed, and the guitar solo he performs is absolutely magnificent. In fact, it’s better than the lyrics, though there’s a fair amount of obscure Britishisms buried in the song (a “three line whip” refers to British parliamentary politics).

“Too Much Information,” the third horn-driven workout in a row, is a groove, and with the shouted “Oh!”s I wonder if the band had been listening to Fela Kuti—or at least the Talking Heads. The lyric, meanwhile, is one that deeply resonated with me in high school: “Too much information/runnin’ through my brain/Too much information/drivin’ me insane.” Stewart’s drums are tight, with only the occasional splash on the high hat or fill at the corners hinting at his prowess. Summers gets to unleash his guitar in the last 30 seconds and it brings the song alive just as it fades out.

“Rehumanize Yourself” continues the horn-driven instrumentation but moves away from funk grooves and back to something closer to New Wave (of course, it’s a Stewart Copeland co-write). The lyrics continue the theme of humanistic opposition to industrialization and racism, and include the only moment in the Police’s work that has made me turn down the volume to avoid playing a four-letter word in front of my kids (“Billy’s joined the National Front / He always was a little runt / He’s got his hand in the air with the other c***s / You got to humanize yourself”). Sting comments on and condemns the undercurrent of violence that causes the police to embrace firearms and leads street gangs to kick immigrants to death and join far right fascist movements. Need I mention the song’s continued relevance?

The follow-up, the reggae-inflected “One World (Not Three),” attempts to offer a recommendation for how, exactly, one is supposed to re-humanize one’s self. Sting takes the perspective that borders are arbitrary human constructs (“lines are drawn upon the world / before we get our flags unfurled”) that distract us from the truth that “we can all sink or we all float / Cause we’re all in the same big boat.” Were it not for the overdubbed saxophone chorus, this song could have fit comfortably on Reggatta de Blanc, as Stewart is let loose to provide any and all drum wizardry that he can.

The mood shifts on “Omegaman,” the sole Andy Summers track. Unlike “Behind My Camel,” all three Police participate on this track, but the expertly layered guitar is the main attraction behind the dystopian lyrics, as we follow a narrator contemplating suicide through deserted streets beneath “skies alive (like) turned-on television sets” (William Gibson, call your office). Apparently this high-energy track was originally supposed to be the lead single from the album, at least in the mind of A&M Records executives, before Sting put his foot down and insisted that it not be issued. (Small wonder that stories continue to be told of the bad blood between Sting and Summers.)

“Secret Journey” opens with the last new instrumental sound the band pioneered on the album, the Roland GR-300 guitar synthesizer. The story, about a man seeking joy in sadness and the “love you miss” from a blind holy man, revisits the plight of lost love that appeared in their earliest songs. But where the narrator of “Does Everyone Stare” or “Can’t Stand Losing You” wallowed in self-pity, this narrator’s fate is ambiguous. Did he find the love he missed, or did he make his secret journey, become a holy man, and ultimately abandon his original goal? Sting’s purported inspiration for the song, Meetings with Remarkable Men by the mystic George Gurdijieff, would suggest the latter. But this path to re-humanization feels quantifiably different from that suggested in the earlier songs, seeming to lean toward a path of abstinence and avoidance of other people. We’re in a darker place as the song draws to an end.

Literally so, as the portamento bass note leads us into “Darkness,” Stewart Copeland’s brilliant drum work our guide as synthesizers and guitar accompany us ever deeper on our journey. Copeland wrote the song, and in it we begin to hear articulated some of the threats that would ultimately tear the band apart: “I could make a mark if it weren’t so dark / I could be replaced by any bright spark… Instead of worrying about my clothes / I could be someone that nobody knows.” But if the lyrics explore the temporary prison of fame, the song is a perfect blend of high hat, saxophone and guitar, and the crackling thunder of the snare.

Ghost in the Machine was a big step forward for the Police, in terms of popular recognition and sales, as well as in songwriting and the making of a coherent concept album. But the forces that pulled them along the path to greater market success were also pulling at the carefully knotted strings that held the trio together. Soon after the recording of Ghost, one of the members was getting his first taste of life as a solo performer. We’ll check that out next time.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

BONUS: Some of the b-sides for Ghost in the Machine were fantastic. We’ll get to my favorite one soon, but “Shambelle,” which appeared as the b-side for “Invisible Sun” (and “Every Little Thing” in the US), is a great instrumental—much better than “Behind My Camel,” which actually won a Grammy for best instrumental rock performance.

- Thanks to the reference in “Don’t Stand So Close to Me,” I searched my local public library shelves (shout out to Grissom Library) for Nabokov’s works and was reading his collections of short stories and translations of his early works in my senior year of high school. I ended up taking a course on Nabokov’s novels during my third year at the University of Virginia, studying with the great Julian Connolly, during which I read just about everything Nabokov had published, including the astonishing late novels Ada, or Ardor and Pale Fire. I highly recommend taking the opportunity to go down a rabbit hold of this kind if you ever get it. Hey, who said rock isn’t educational? (And what would have happened if I went down an Arthur Koestler rabbit hole instead?) ↩︎

Should have mentioned… this is one of the rare cases where I actually know where and when this album entered my collection, since I blogged about it in March 2004.

On 7July1980, I had just left my pathologically quaint hometown of CarmelCA for the greener(&darker) pastures of SanFrancisco but 1981 was my first full year there, and Ghost always will be a soundtrack of that time – when I actually could buy booze without worrying about my fake ID.

I always felt it was their best album so far: Regatta was fun&solid but Zenyatta had a thrown-together/ rush-job feel to it whereas Ghost has a perfect beginning+middle(with the horns!)+end; Darkness made me fall in love with Stewart and may be one of the best album closers of all time. (And it even as an opener for many MixTapes since then.

Synchronicity was released after my return home (temporary, due to an ailing grandmother whom nobody else seemed like) but the one song I truly loved was O My God, and only recently did I learn that it had been recorded 2 years earlier so that made PERFECT sense!

Many thanks for your astute breakdown of a genuinely fabulous album from early in the Reagan/Thatcher era – along with Sandinista, I always seemed to on of the 8 albums sides on my turntable for over a year (plus RemainInLight & ScaryMonsters, of course).

Thanks again!

Mark (now in Portland).