Album of the Week, December 21, 2024

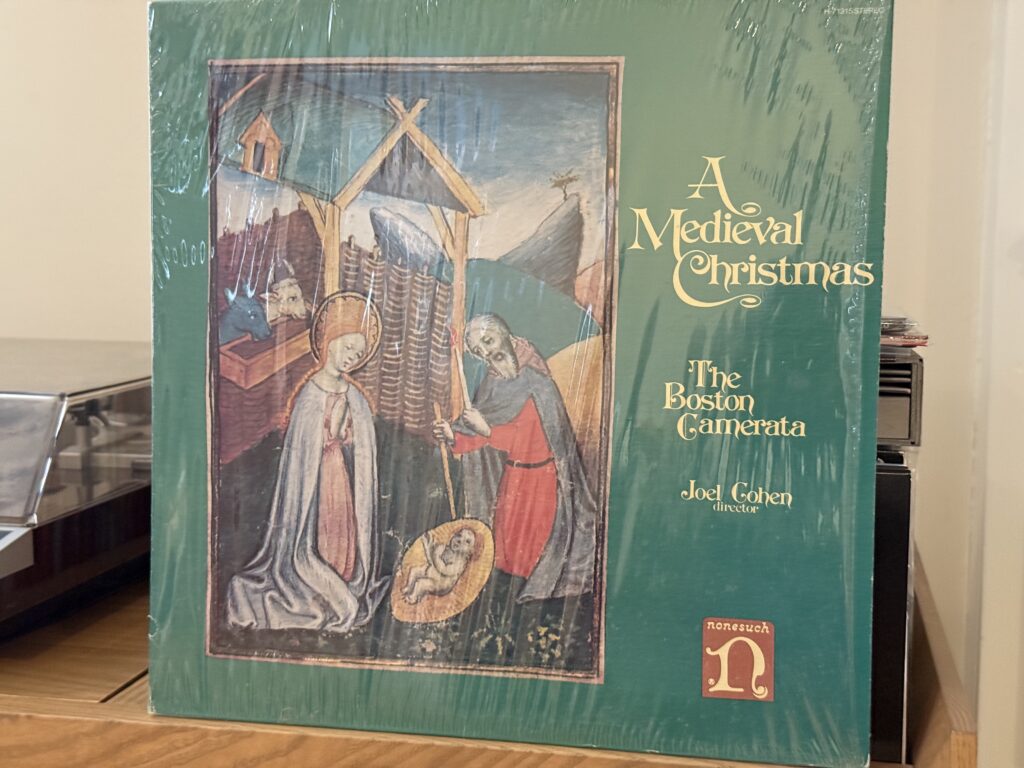

I’ve featured the Boston Camerata in this series before (and even before this series was a thing). The early music ensemble, directed for many years by Joel Cohen, was responsible for introducing me to the sound of Middle English, Renaissance and Sacred Harp music, and a great many other things. And before I started collecting old records, I thought they had recorded three Christmas records for Nonesuch: Sing We Noel first, then A Renaissance Christmas, and finally A Medieval Christmas, which I thought had been released in 1991 when it came out on CD.

It turns out I had things backwards. As I wrote last year, the Nonesuch A Renaissance Christmas was a re-recording of an earlier performance from before the Camerata had signed to a major label. And it turns out that A Medieval Christmas was originally released in 1975, meaning that it precedes Sing We Noel by a full three years.

That difference is significant. Thanks in part to Cohen, as well as to British early music artists like Paul Hillier and David Munrow, the standards for early music performance were rising rapidly, and certain scarcities like authentic period instruments and unusual voice parts (like countertenors) were starting to be more widely available. Indeed, the scarcity of early instruments was, um, instrumental in the founding of the Camerata; it began as a group dedicated to demonstrating the rare antique instruments in Boston’s Museum of Fine Art, and this album was recorded at the MFA.

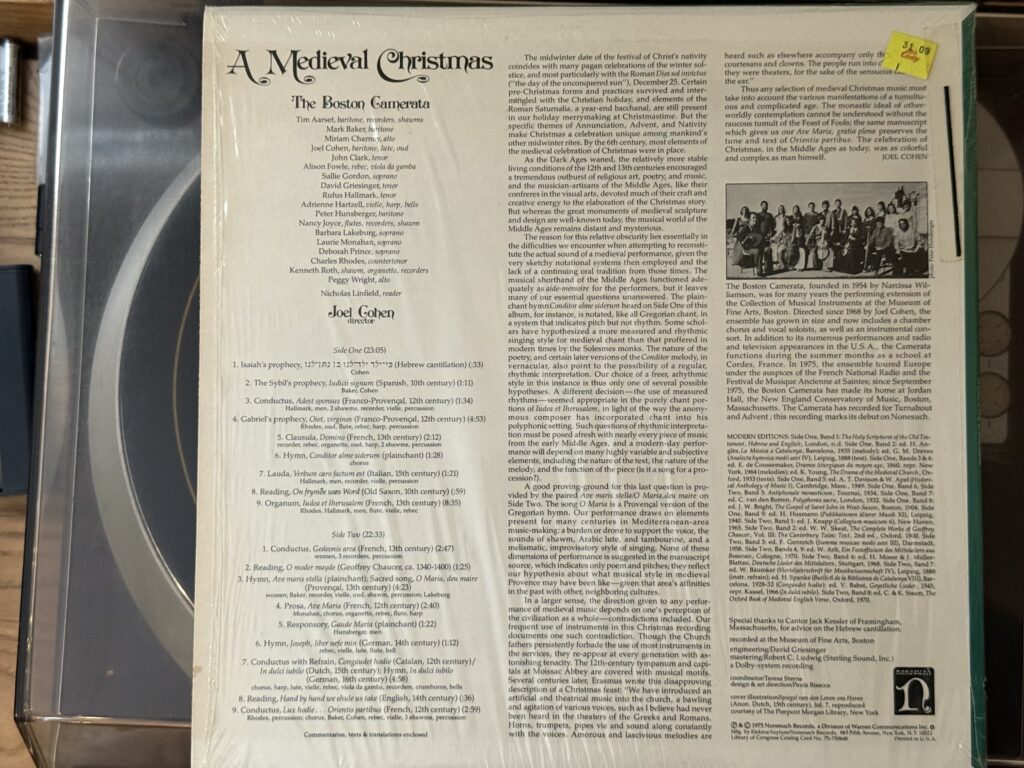

But during this transitional period, Cohen still had to work with the forces he could find, including some interesting vocalists. Charles Rhodes, the countertenor who is featured prominently on the Franco-Provençal setting of the prophecy of the Angel Gabriel, “Oiet, virgines,” is probably the most notorious example; he has an expressive voice, but his vocal production is a little uneven and he strays a little toward the pinched and strained side of the high tenor sound. But it’s still mesmerizing, and that’s due at least in part to the program and the instrumentalists.

Cohen can be reliably counted on to deliver the most incredibly obscure music, whether a cantillation of the Torah or a 10th century Spanish plainchant, and then to weave them together seamlessly into a single performance. When the conductus “Adest sponsus” enters, it’s with great vigor that the percussion and the shawms set the tempo, as if for a procession; the album closing conductus “Orientus partibus” is actually performed as a recessional, which contributes greatly to the mood if not to the audibility.

There is also some fairly spectacular programming of related tunes together, with the familiar macaronic carol “In dulci jubilo” paired with its plainchant antecedent, “Congaugent hodie,” as well as readings in Middle English courtesy of Nicholas Linfield (who also did the readings on Sing We Noel).

The album as a whole can be taken as many things: a scholarly illustration of medieval musical practices (especially if you read Cohen’s comprehensive liner notes while listening), a window into alternate musical Christmas traditions, or just something to put on and meditatively listen. Or all of the above, which is what I plan to do this week. Next time, we’ll get to something a little funkier.

You can listen to this week’s album here: