Album of the Week, November 30, 2024

When Wayne Shorter died, on March 2, 2023, in many ways it marked the end of an era. By the time of his passing he was being hailed as America’s greatest living jazz composer, and the “Footprints Quartet” that we heard last week had a reputation as one of the greatest improvisational bands in history. In some ways, though, his death accelerated the release of material by the quartet, a flood that began with a trickle following his retirement from performing in 2018. Some of the works released featured other ensembles; the last album released before Shorter’s death featured him in a new quartet with Esperanza Spalding, Teri Lyne Carrington, and Leo Genovese, from a festival appearance the summer before his retirement, and other ambitious recordings combined the “Footprints Quartet” with an orchestra (we’ll review the most notable of those another day).

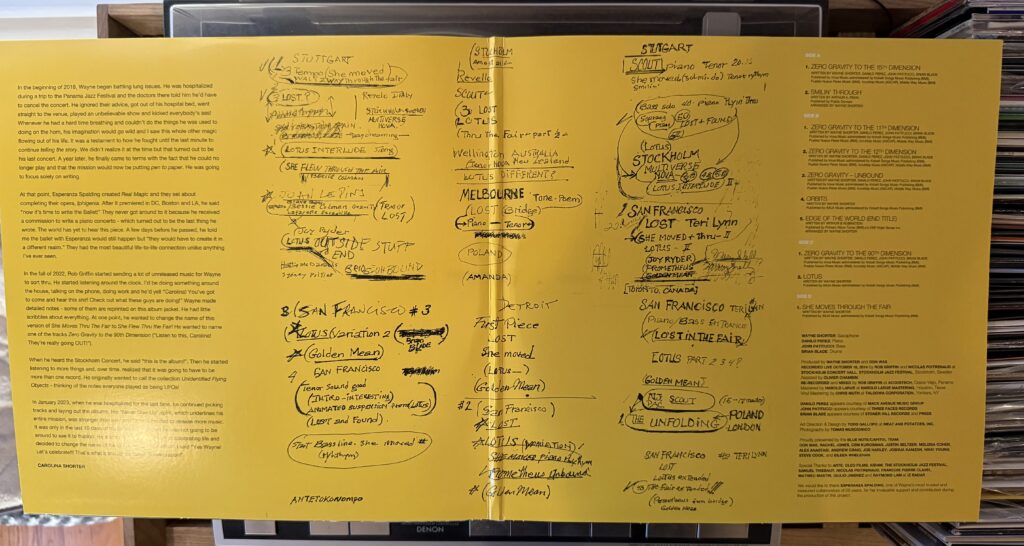

But today’s record, the evocatively titled Celebration Vol. 1, is a pure representation of the Footprints Quartet at the height of its powers. A live-in-concert recording from an October 18, 2014 appearance at the Stockholm Jazz Festival, it features only a few recognizable Shorter compositions alongside many collective group improvisations. At one point, Shorter thought to title the record Unidentified Flying Objects, after these improvisations, and they do feel a little like invaders from outer space in the way they arrive and transform.

“Zero Gravity To the 15th Dimension” opens as a mysterious minor-third centered tune by Pérez and Patitucci, with rolling thunder under provided by Blade. Starting out on single notes, Shorter builds to an obbligato of mysterious tones that transform into a sort of sonata, with all three melodic players essaying the melody over Blade’s cymbals. A single beat on the bass drum signals the start of a 4/4 section and the return of the chromatic tune from the beginning. The band returns to a more melodic land built approximately around the chords from “Orbits” for a few bars, then turns to a new mysterious modal tune driven by a rising pattern in Patitucci’s bass; they gradually build in energy and dynamic before settling into a tune atop his constantly moving, restless arpeggios. (Hearing him after last week’s first outing of the “Footprints” quartet, it becomes clear just how much the bassist was contributing melodically and improvisationally by this point to the quartet.)

The band draws this number to a close and launches without a pause into “Smilin’ Through,” notionally a cover of the 1919 song by Arthur Penn but thoroughly transformed by Shorter’s arrangement and his playing, which channels some of John Coltrane’s melodic imagination in a far gentler expression. Pérez plays the melody as a gentle modal exploration while Shorter plays obbligatos over and around the tune and Patitucci and Blade create a sternly rhythmic pulse.

Side 2 opens with a series of brief explorations, played without interruption but labeled on the cover as “Zero Gravity to the 11th Dimension,” “Zero Gravity to the 12th Dimension,” and “Zero Gravity – Unbound.” The first opens as though it will be a pop song before turning into a fluttery exploration of beyond. The second begins with a bass figure that is then punctuated by stabs of chords in the piano, and isolated notes from the saxophone. All the players coalesce into an oddly sprightly tune that transforms into the “Unbound” version—a freer playing of the tune in the same key that circles around an oddly familiar set of chords.

A quick whistle signals the opening of “Orbits,” which reveals itself to have been the source of the familiar chords. The melody circles in the piano and the saxophone, and then the players take a step sideways and find themselves in a different tonality, even as Patitucci intones the theme again. They play the theme out and into a different feeling once again, as if they opened the door to a Latin ballroom. This may be the definitive version of “Orbits” by virtue of the way it jumps from planet to planet, each time with the swirling theme signaling the transition. The piece ends with a stuttering version of the theme, accompanied by descending whistling, as the band comes back to earth.

“Edge of the World (End Title)” is a Shorter arrangement of the end theme of the 1980s movie Wargames, written by film composer Arthur Rubinstein. (Yes, really. Shorter was a notorious science fiction buff, and was watching hours of old movies in his Los Angeles home between tours at the end of his life.) Here it’s a solemn and straight reading of the tune to close out the most exploratory, gnomic and fascinating side of the album.

“Zero Gravity to the 90th Dimension” opens with a thudding percussive roll on muffled drums, followed by stabbing chords and a sustained trill from the piano and a bowed eerie note from the bass. Shorter transitions the band out of the Zero Gravity moment with a completely unaccompanied melody, signaling the opening of “Lotus,” a Wayne Shorter original that only appeared on one other album, his 2018 magnum opus Emanon. Here it reveals itself as a tender melody that plays suspended over the chords that were in the 90th dimension previously. At one point the band quotes something that sounds for all the world like Radiohead’s “Everything In Its Right Place,” and it seems as though it fits right in, as does a fleeting quotation by Shorter of “Tomorrow” from Annie. The band reaches a climactic shout that draws to a close with Pérez’ piano.

The final side of the record is a twenty-minute-long performance of the folk song “She Moves Through the Fair.” This folk song, popularized by Fairport Convention among others, became a signature tune for the Footprints Quartet on Shorter’s 2003 album Alegría and he would revisit it on Emanon. The Fairport Convention version feels like the point of departure for the slightly Middle Eastern influenced introduction from the rhythm section; it’s not until almost five minutes in that Shorter joins to play the melody over the unfolding exploration. The band shifts gears about halfway through into a different mood, seeming to play a suite within the performance. Something that this last song brings home more than anything is the quartet’s unique ability to improvise collectively—not in a free jazz sense, but with all four players finding a collective, coherent melodic sense at each moment, so that in a split second they could switch from tender and delicate to pounding to melancholic to triumphant. Shorter, who was always more deeply thoughtful about his compositions than he let on, may in fact have composed some of the transitions, but they seem so effortless that overall they feel like dancing en pointe on a tightrope.

Celebration Volume 1 is the end of this second run of reviews exploring the works of Miles Davis’ band, both during their association with the great trumpeter and afterwards. But just as this record signaled a new effort to bring Shorter’s works before the public, the Miles series will be back as I find more to explore… and add it to my collection. (Hey, I do it so you don’t have to find the shelf space for all of these records!)

We’ll take a break for the annual Christmas records series next week as we head into the holidays, and then turn our attention to something completely different, sort of, in the new year.

You can listen to this week’s album here: