Album of the Week, October 26, 2024

As we saw last week, Herbie Hancock was at a crossroads in 1976 when he assembled his retrospective concert, later released as V.S.O.P. He could have doubled down on the jazz-funk that had been an ingredient of his music since the beginning and had been in overdrive since the release of Head Hunters. He could have returned to the intensely cerebral, far-out sounds of the Mwandishi band. (Somewhere there is a world in the multiverse in which the Mwandishi band kept playing and getting further and further out there, until radio transmissions of its shows were intercepted by aliens who returned to take Herbie home.)

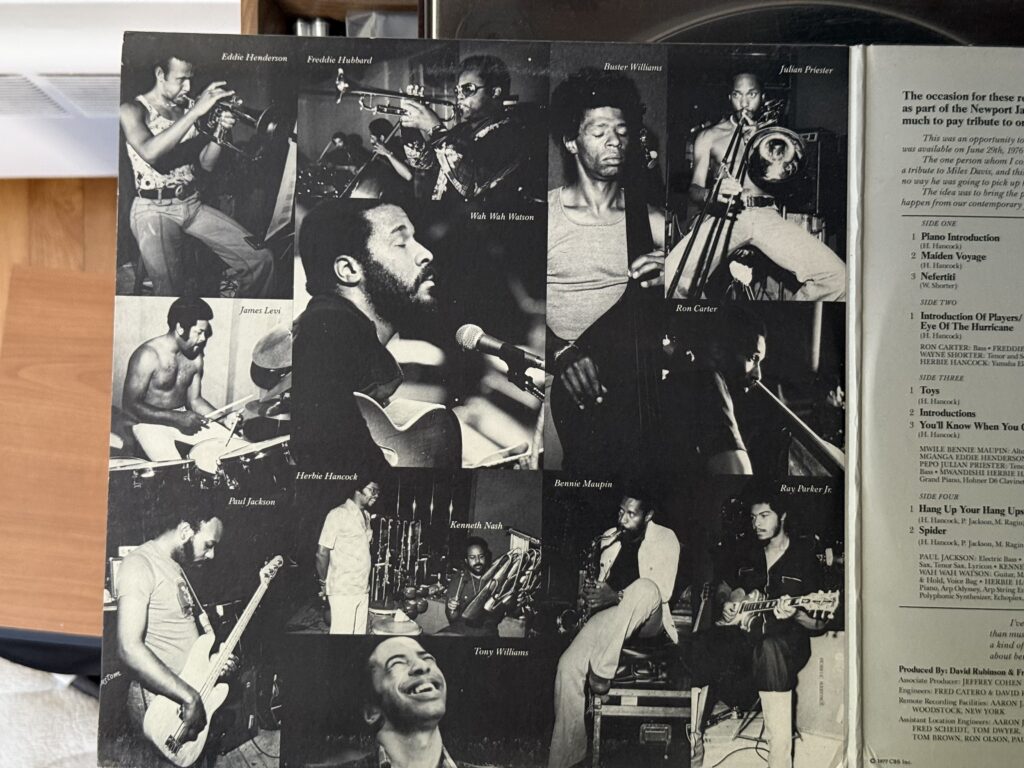

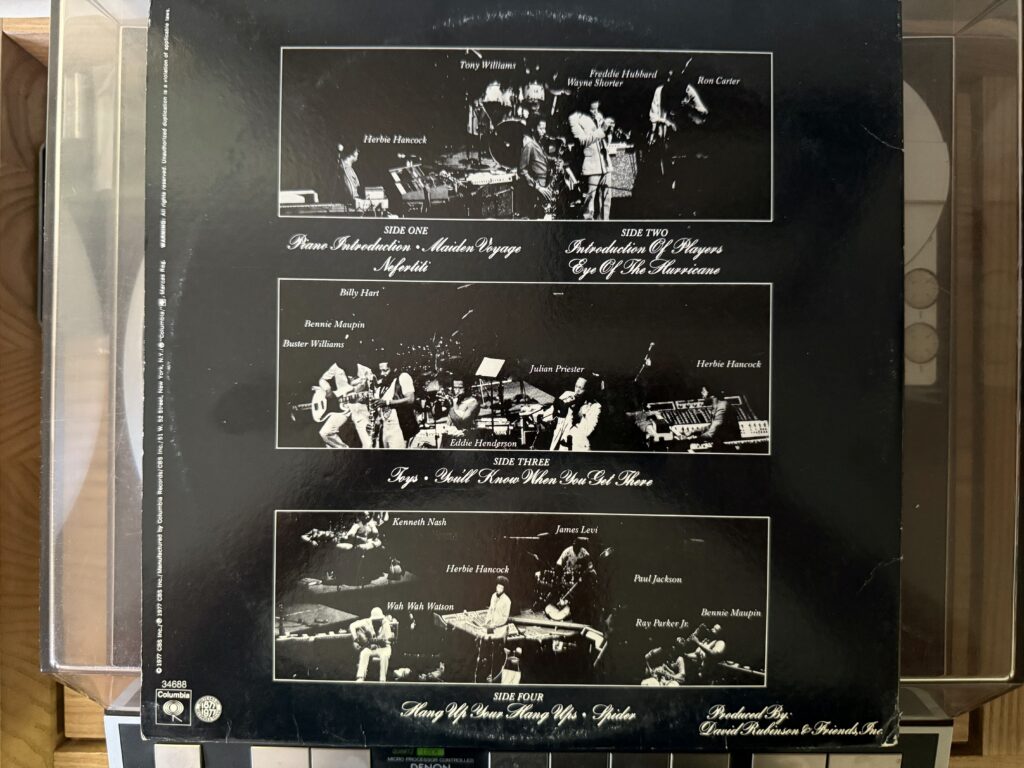

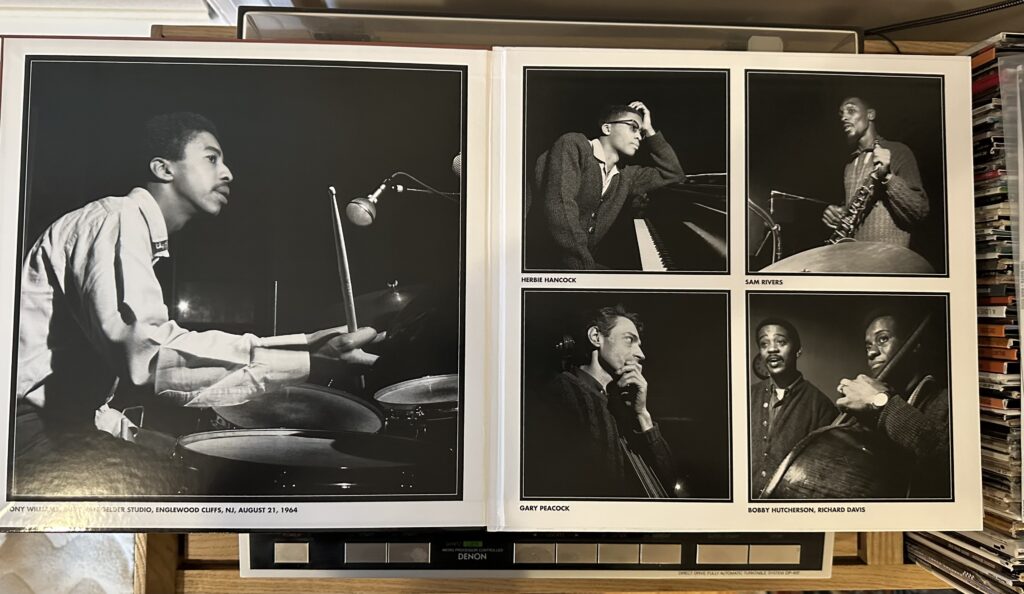

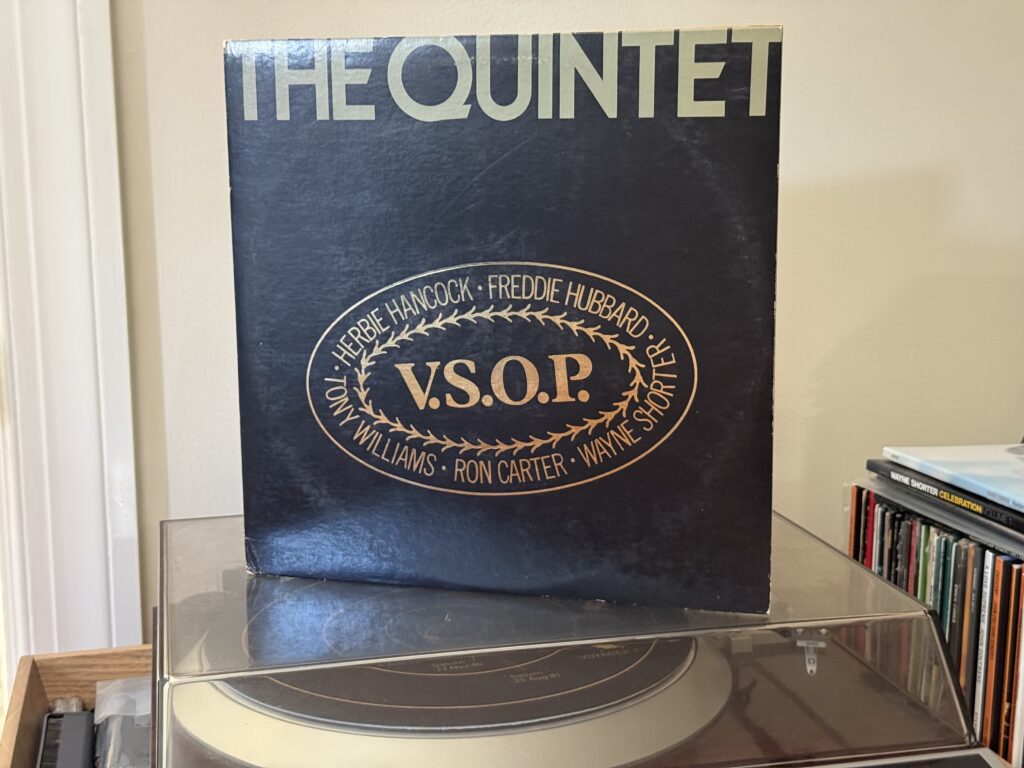

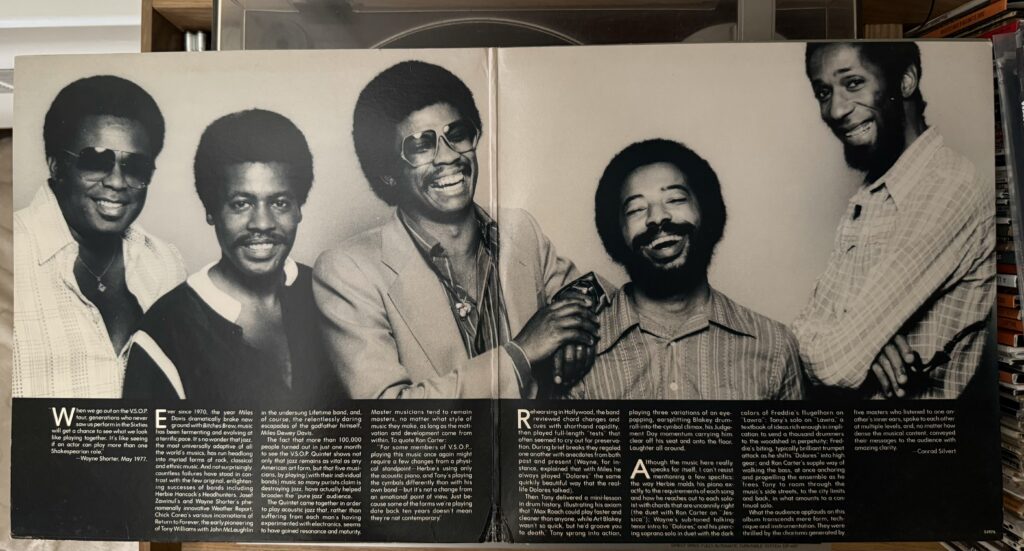

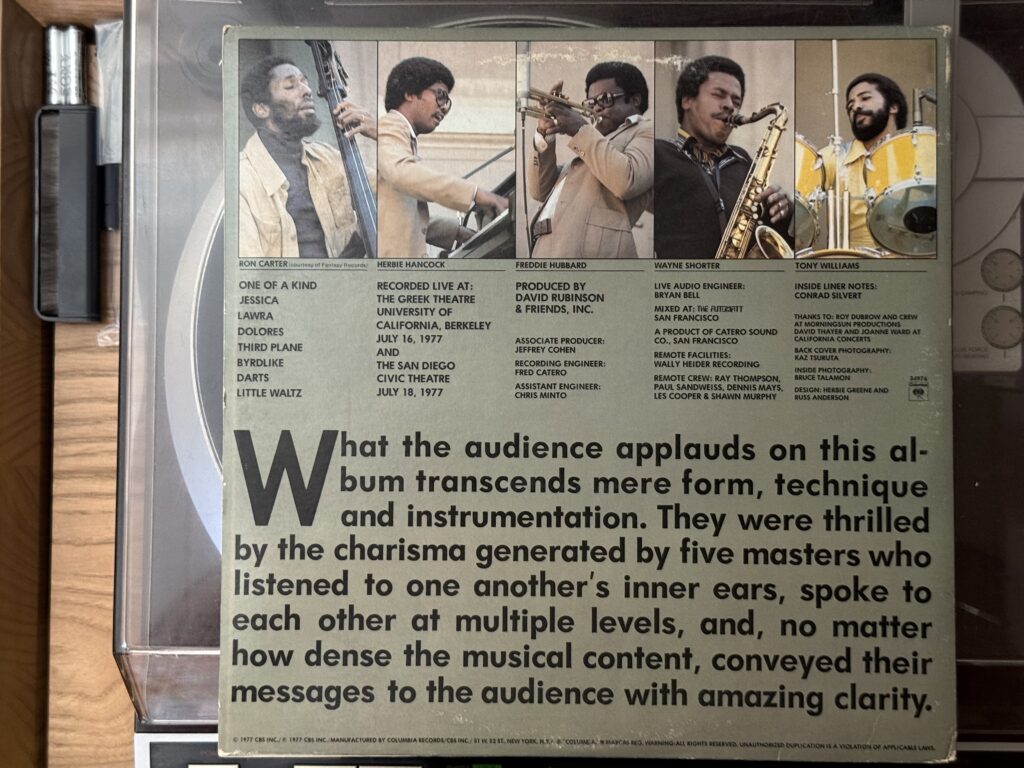

But instead, he kept going with the quintet that he had reformed from Miles’ Second Great Quintet, with Freddie Hubbard continuing to play the role of trumpet. The musicians did some studio sessions together; a day-long session on July 13, 1977 with Herbie, Ron Carter and Tony Williams saw tracks released both as Herbie Hancock Trio and as Carter’s Third Plane, with all three contributing to the compositions on the Carter album. And on July 16, the three musicians were joined by Wayne Shorter and Hubbard in a performance at the Greek Theatre at UC Berkeley, and then a second at the San Diego Civic Theatre on July 18. They were billed as V.S.O.P., and a live double album combining highlights from both shows was released in October 1977.

“One of a Kind” is one of two Hubbard compositions on the record, and one of two compositions that make their first appearance here. The band starts with a Tony Williams drum roll and arpeggios from Hancock, and then a fast beat on Carter’s bass. The horns come in with the melody, and we’re off to the races. As often happens in a Hubbard composition, the melody consists of a descending arpeggio, played precisely and cleanly. His tone is still a marvel at this date, taking all the pristine bell-like quality of a young Miles and turbocharging it. When Shorter comes in, it’s from left field, not directly following Hubbard’s lead but picking up a thread of his solo and deconstructing it. Hancock responds, not playing chords under his solo but responding to Shorter’s assays with terse runs and replies. Wayne eventually follows Hubbard into the stratosphere, but instead of soaring he swoops up and down in jagged attacks. Hancock flourishes a series of arpeggios in response to Shorter’s solo but drops back into a Twilight Zone-esque vamp behind Carter’s insistent rhythm as the horns return to play the head once more, closing on a high supertonic.

“Third Plane” was recorded three days prior as the title track to Carter’s album, but you’d never know the quintet hadn’t been playing it for years if Hancock didn’t announce it at the top. The Carter original is taken at a faster clip here, and the two horns dialog with each other over a melody that seems taken equally from Carter’s bassline and Herbie’s piano lead. In its quintet version the 8-bar modulation that lifts the tune briefly from B to B-flat is somehow less strange and more natural, maybe thanks to Shorter’s straight-ahead-with-a-twist solo. Hubbard plays flugelhorn for his solo, finding a pattern that he tosses back and forth with Herbie, before yielding to the piano, who plays what sounds like a stride-influenced solo over Carter’s insistent walking bass. Carter and Williams take a quick sixteen bar intro to the last two returns of the melody, and the band seems reluctant to let the tune go, hitting the end three times before bringing it to a close.

“Jessica” sees a welcome return of the sad ballad from Fat Albert Rotunda. Hancock outlines the chords while Carter and then Hubbard play the melody, followed by Shorter; the latter plays as if choking off a sob. Hubbard’s solo seems to consider all the different corners of the melody in a solo that’s less than 60 seconds long. When Shorter returns for his brief solo, it is with breathtaking sustained notes that seem to underline the sorrow in the work. Herbie’s solo, which takes three verses, plays with restraint and delicacy, accompanied only by Carter and the barest hint of Tony Williams. The horns return for one more run at the melody, then fall back as Carter and Herbie take the tune to an end.

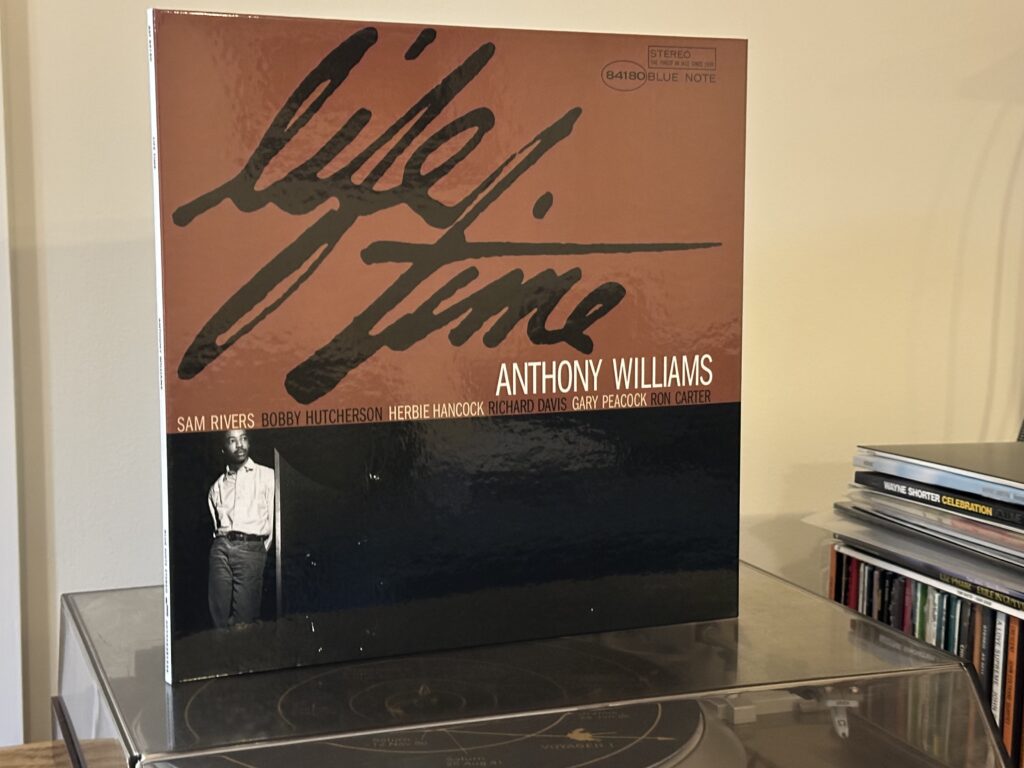

“Lawra,” a Tony Williams composition from the Third Plane/Trio sessions, Herbie begins with a riff in parallel fourths that could originate anywhere from Aaron Copland to nursery school to—as Williams enters on massive drum hits—a classic rock song. The rest of the band joins in to state the theme, with Hubbard and Shorter already trading beats, and thoughts, in the introduction. They continue this way for two full iterations of the tune before Herbie falls back and they continue to duet through the first pass. (An aside: the engineering on the album is superb, especially for a concert recording; the presence in this tune makes you feel as though Freddie Hubbard is standing just to the left of you while Shorter is somewhat to the far right side of the stage, a bit of stereo separation that’s particularly effective here.) The rest of the quintet drops back as Williams plays a polyrhythmic solo that leads back into the opening riff.

After an introduction of the players, “Darts” is a Herbie composition that here makes its only appearance in his discography. It’s a gnarly tune in a minor key, so naturally Wayne takes the first solo. Freddie Hubbard plays a solo that darts around several different modes before entering a give-and-take with Herbie. Herbie then improvises an extended run that centers on a diminished triad before returning to the head. It’s a nice enough track, but it’s clear why Herbie didn’t return to it.

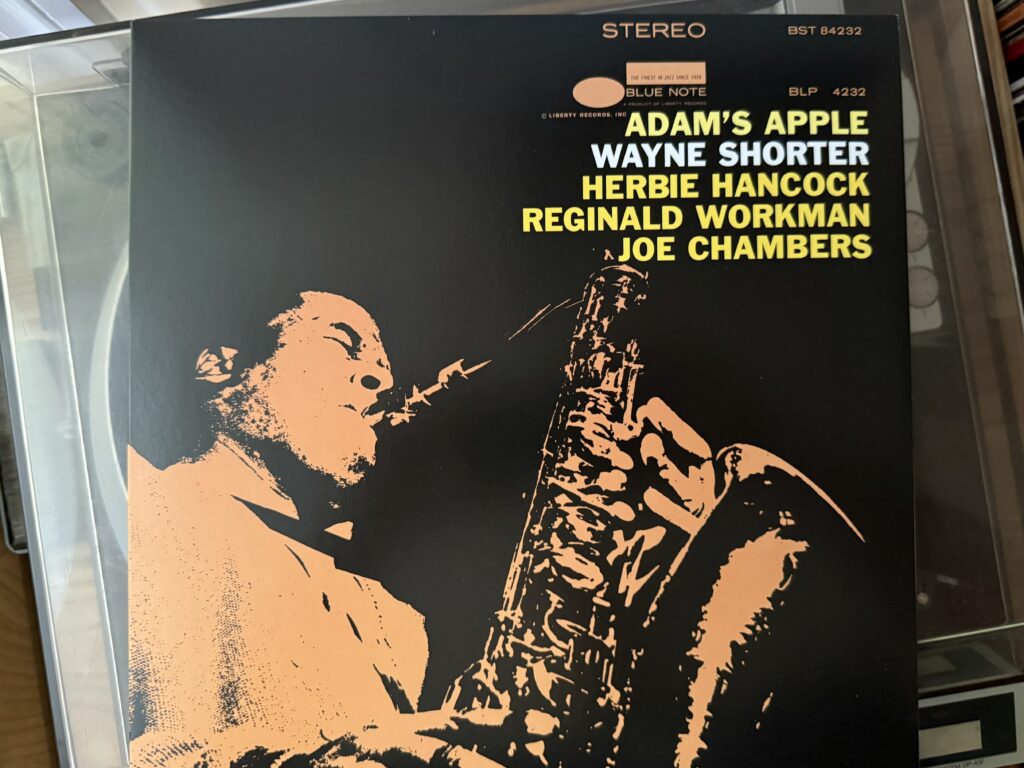

By contrast, “Delores,” by Wayne Shorter, is the song with the second-oldest roots on the album, having been first recorded by Miles’ quintet on Miles Smiles. Wayne essays the melody by himself for the first ninety seconds in free time, then gradually speeds up to performance tempo and is joined by Carter, Hancock and Williams. Hubbard enters as the band plays the opening melody together, then Wayne takes an extended solo that trades ideas with Herbie. As with the original recording, Herbie soon lays out, so he’s accompanied only by Carter and Williams. Ron Carter can be heard throughout, first walking the line, then improvising along the scale, sometimes down alongside Williams holding down the low end, then sliding up into a higher improvisation. Herbie signals the end of Wayne’s solo and anchors Freddie’s, not playing through but trading ideas with him. Tony Williams turns on the energy throughout Freddie’s solo, burning up the cymbals. The players then take an extended coda that improvises on the penultimate tone, trading ideas before returning once more to the head. This performance, more than any other, earns the blurb on the back of the album: “the charisma generated by five masters who listened to each other’s inner ears, spoke to each other at multiple levels, and, no matter how dense the musical content, conveyed their message to the audience with amazing clarity.”

For my money the band only runs low on steam on the penultimate number, “Little Waltz.” This is the other Carter composition on the record, having made its debut earlier that year on Carter’s solo album Piccolo. It’s a slow waltz that opens with Shorter and Carter duetting. The rest of the band enters, taking turns on the tune, but the tempo never gets faster than sleepy, though Shorter tries his best to pep it up in his extended solo. The closer, “Byrdlike,” is the second Hubbard composition and is also the oldest on the record, having first been recorded on Hubbard’s 1962 Blue Note album Ready for Freddie. The band has a merry romp through it at something like twice the tempo of “Little Waltz”; true to the name, Hubbard keeps his solo solidly in the hard bop lane, with echoes of Donald Byrd in his solo. Williams trades bars with Shorter, then Hubbard, and then slips directly into a fierce drum solo. The band briskly closes out the tune, with Hubbard and Shorter taking turns to see who can close out the number on the highest note.

Hancock and the quintet could easily have filled an entire evening with performances of compositions they played with the Miles Davis Quintet. That they chose to foreground material from an album recorded just a few days before shows that they were still dedicated to creating new music. The quintet would continue to record its live shows; the Tokyo Tempest in the Colosseum recording, also made in 1977 just a week later, is more of a “greatest hits” concert but demonstrates enormous firepower. They hit the road once more in 1979 and even went into the studio to record Five Stars, but after that the players didn’t get together again until the early 1990s. But Herbie Hancock, in particular, continued to explore new ways into his compositions, and we’ll hear another approach next time.

You can listen to this week’s album here: