Album of the Week, September 14, 2024

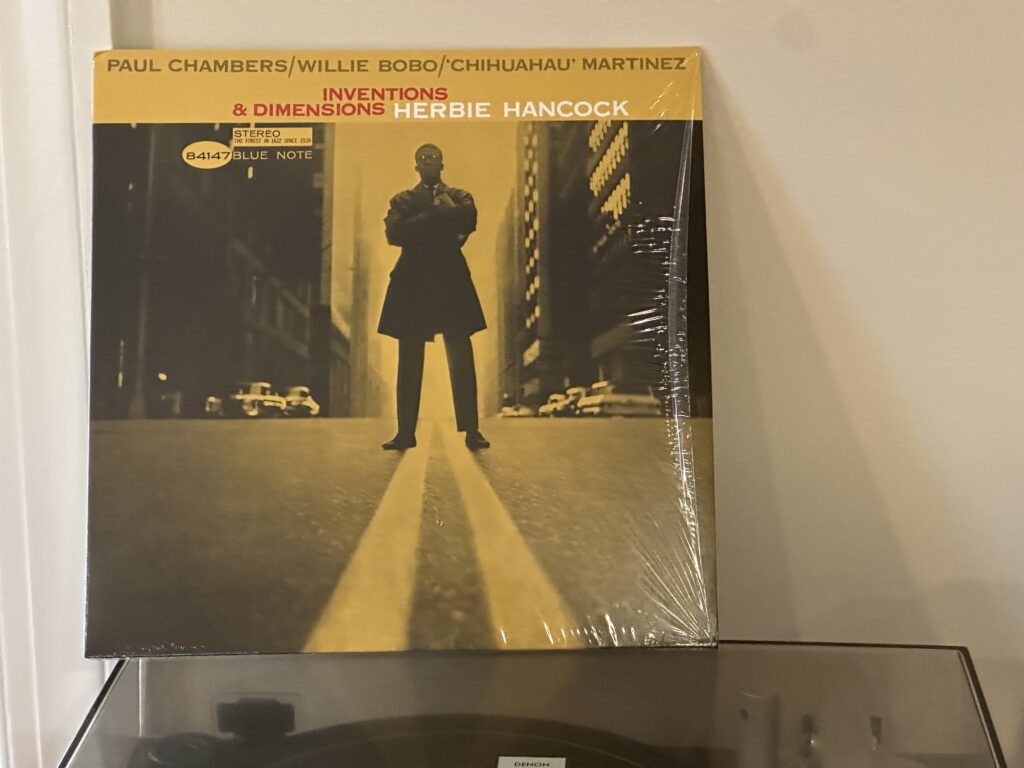

When we looked at Herbie Hancock’s career before joining Miles Davis’s quintet before, we heard his first two Blue Note albums and then jumped to Miles in Berlin. But he had a very busy 1962 through 1964, releasing an album a year (or more) under his own leadership as well as touring with Miles. Today we look at the most unusual of the albums from that early Blue Note period, Inventions & Dimensions, recorded on August 30, 1963 at Rudy Van Gelder’s Englewood Cliffs studio.

While the album is far from atonal, it’s definitely one of Herbie’s more experimental outings. Rather than the more traditional hard bop small groups of Takin’ Off and My Point of View, this session finds him with Latin drummer and percussionist Willie Bobo. Bobo grew up in Spanish Harlem and studied with the great Mongo Santamaria and recorded with Mary Lou Williams, before joining Santamaria in Tito Puente’s band. The two percussionists left to work with vibraphonist Cal Tjader in the late 1950s but as of the time of this recording he hadn’t yet made a huge impact outside the bounds of the mambo craze. (That was soon to change.) Redoubtable Miles Davis bassist Paul Chambers and percussionist Osvaldo “Chihuahua” Martinez rounded out the group, but the majority of the interesting musical happenings here are between Hancock and Bobo.

That may very well be because, apart from “Mimosa” on side two, the entire album is made up of spontaneous improvisations by Hancock, with Bobo grounding him with inventive but in-the-pocket drumming while Martinez and Chambers provide color and a heartbeat, respectively. Chambers in particular doesn’t seem to light up in this format and seems content to stay in the background.

But Hancock more than makes up for any reticence on the part of the other band members. Opening track “Succotash,” like its namesake, combines the widely diverse ingredients of the band into a harmonious whole. It begins as an introduction to the band, with Bobo, Chambers, Martinez, and finally Herbie joining over the course of eight bars. The meter is complex in the opening, with Hancock playing triplet rhythms against what eventually turns out to be a straight four in the percussion, for an effect that seems straight out of Steve Reich’s playbook (though the great minimalist composer’s first experiments with phasing were over a year away). Herbie plays a bunch of different tricks with the track-length improvisation here, going back and forth from the triple meter to straight time before finally returning to a triple meter crescendo. The one moment that Herbie drops away gives Bobo and Martinez the chance to play against each other, and the rhythms are infectious and hypnotic. When Hancock returns, he finds another melodic line before returning to the original triple meter.

“Triangle” begins as a more straightforward blues, but Hancock’s creatively dissonant voicings on the opening chords, sounding like Vince Guaraldi’s “Charlie Brown” theme in two different keys at once, signal that this is going to be anything but routine. The band digs into the pocket anyway, leaving Herbie free to find some deeply soulful patterns over the chords. Chambers may still be somewhat backgrounded throughout but he acquits himself well anyway, the less crowded arrangement here giving him more room to contribute a solid walking bass line. Hancock is still the star here, though, moving from that opening blues line to a pounding improvised passage that sounds a lot like Dave Brubeck in a declaratory mode.

“Jack Rabbit,” true to its name, is a faster romp, and features Bobo on cymbals and Martinez on congas pushing the beat forward. While the opening melody sounds a lot like a faster version of that “Charlie Brown” theme, Herbie’s improvisation overall is freer here, jumping from idea to idea at high speed. This is one that wouldn’t have been out of place (with different percussion) on one of the early Second Great Quintet albums.

“Mimosa” is the sole arranged track on the album, and even it is on the loose side. Starting with a symphonic introduction out of time that feels a bit like Bud Powell’s “Glass Enclosure,” the percussionists take us back into time and lead into Hancock’s main melody, which feels both wistful and romantic in roughly equal proportions—a feat when the melody is arguably just a vamp on the main chord changes. He moves from the initial statement into more elegiac melodic improvisations, all while Martinez and Bobo keep the beat with a steady, gently lilting samba pattern kept fresh by Bobo’s continually evolving cymbal washes. Chambers gets a solo starting at the six-minute mark and it’s a wonder, moving from the slow samba pulse into a double-time excursion around the wobbly rail of the changing chords. Overall though the track stays just on this side of disappearing into the background.

The album closes with “A Jump Ahead,” which is impelled by the urgency and drive of Bobo’s drums and a recurring movable octave in Chambers’ bass that sounds on wherever Herbie’s melody lands. The improvisation appears to center around these jumps of the melodic path, from the tonic to the sixth to the minor third to the fifth, with various exciting things happening in between. Herbie’s solo is more like his later work with Miles here, the chordal structure notwithstanding, in that he organizes his improvisation around an increasingly widening gyre of a right hand solo with sparse left hand accompaniment. And it does seem to be deeply improvised; you can even hear him doing the Bud Powell/Keith Jarrett sung accompaniment, a tribute to how deeply he’s concentrating throughout. Before taking it back to the melody, he bangs out a high rhythmic pattern on a single tone (in octaves), and then closes it out with a vamp on the tonic to the supertonic. It’s high concept in composition, but almost funky in execution.

Inventions & Dimensions is misleading in its seemingly casual nature. While much of the material is clearly freely improvised, it has early-1960s Herbie Hancock doing the improvisation, and that’s worth two or three lesser composers’ worth of fully fleshed out material. While the four musicians here never worked together again, the album stands as testimony to Hancock’s willingness to go far afield—a tendency we’ll see in spades on his more “conventional” album next week.

You can listen to this week’s album here: