Album of the Week, September 28, 2024

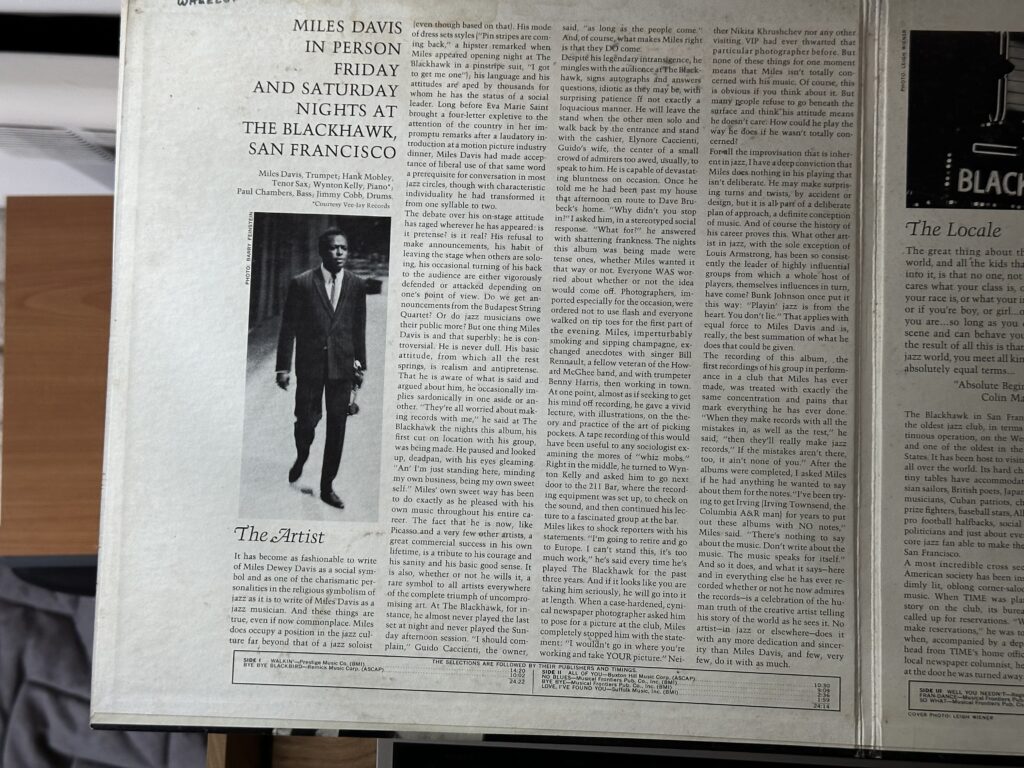

Miles’ Second Great Quintet took a while to gel, and the hardest position to settle was the second horn. Miles had worked with John Coltrane in the first quintet, and whether through conscious comparison to that titan’s stature or by some other means, the saxophonists—including Hank Mobley and George Coleman—who joined the quintet would leave without making much of an impact. It took the arrival of Wayne Shorter in late 1964 to bring all the pieces together; we’ve listened to the document of that beginning, in the recording of a live performance of the quintet from September 1964 released as Miles in Berlin.

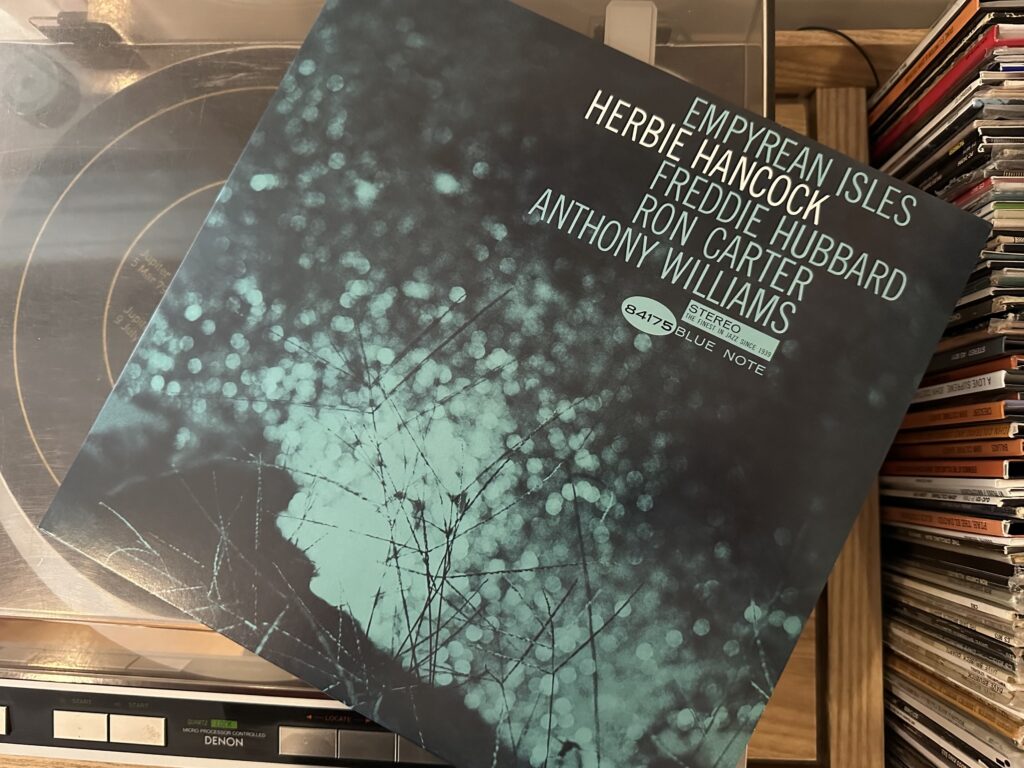

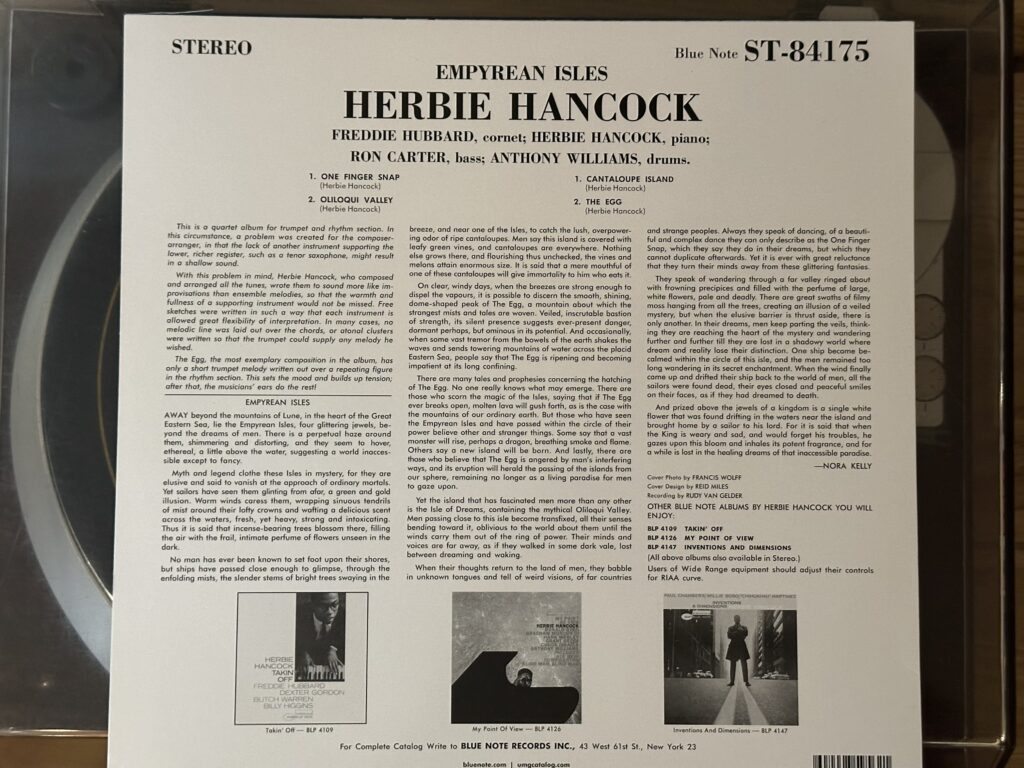

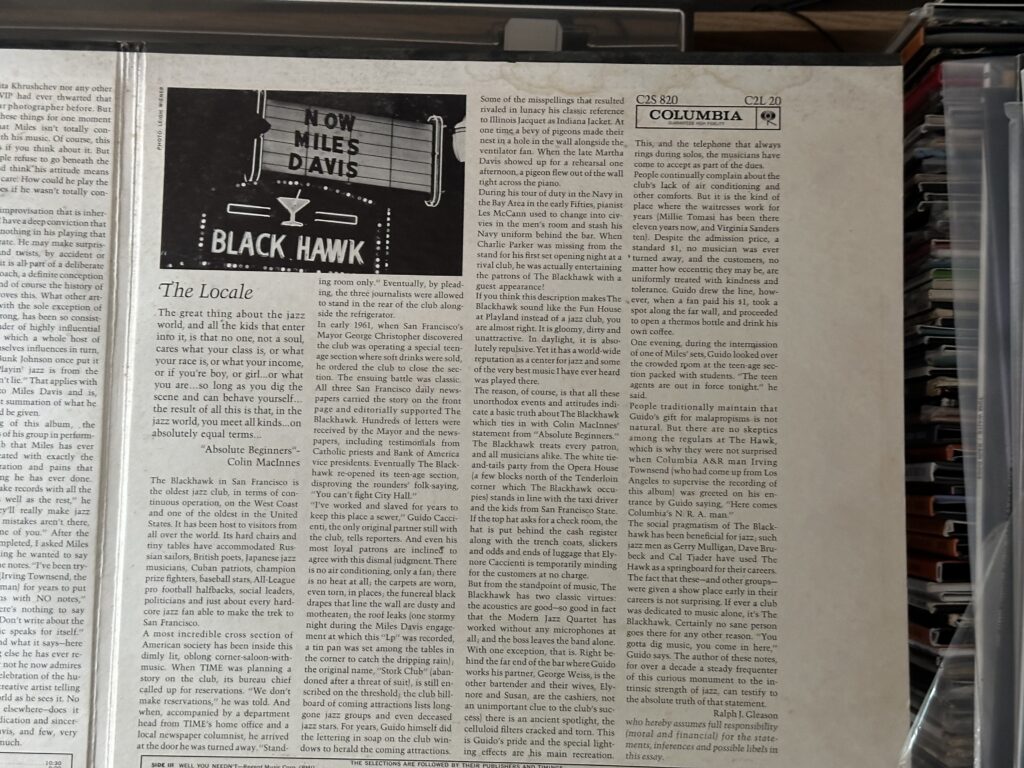

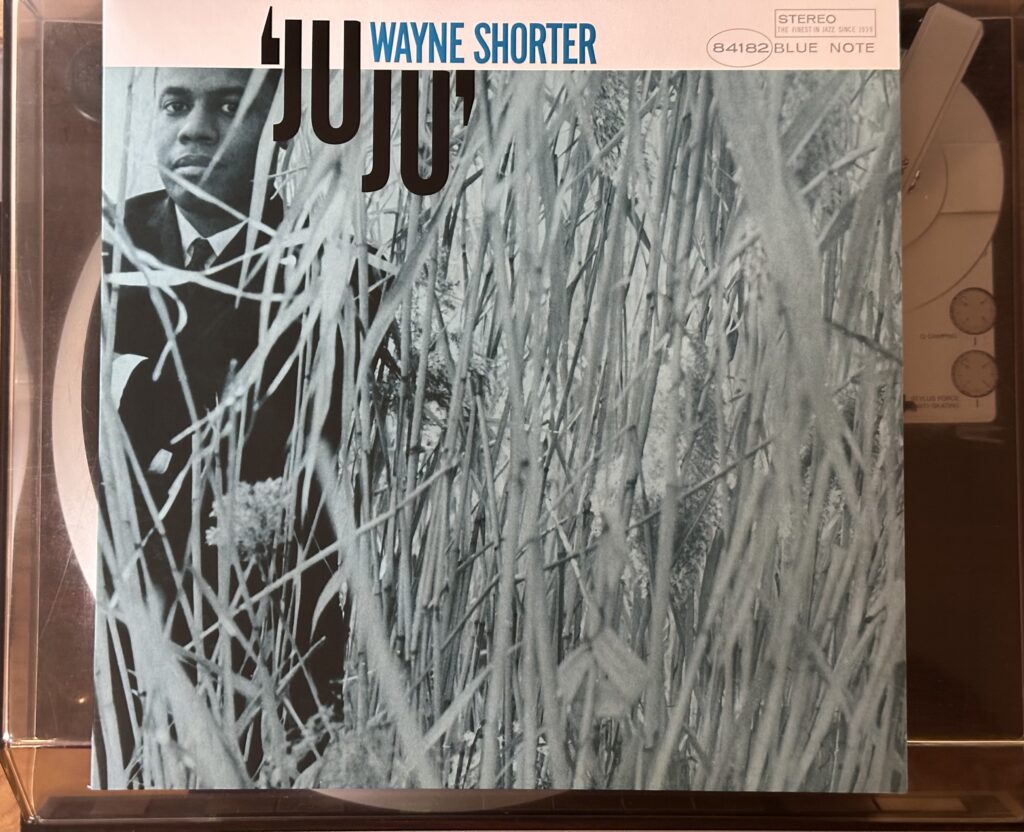

But Shorter was hardly sitting on his hands prior to joining the quintet. In April 1964 he recorded his first album as a leader for Blue Note Records, Night Dreamer. He followed this with today’s session, recorded August 3, 1964 at Van Gelder Studios in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, just about six weeks after Herbie Hancock’s session that became Empyrean Isles. Unlike Hancock’s session, though, JuJu featured not his bandmates in Miles’ quintet, but the rhythm section of a different saxophonist entirely: McCoy Tyner, Elvin Jones, and Reggie Workman, all of whom had worked with John Coltrane. In fact, Tyner and Jones had been in Van Gelder’s studio with Coltrane a week after Hancock’s band, on June 24, 1964, recording the tracks that would be released over fifty years later as Blue World.

The use of Coltrane’s rhythm section was controversial at the time for Shorter, who was fighting a mistaken impression in some quarters that he was only a Coltrane imitator. But JuJu would prove how wrong that impression was by foregrounding not only Shorter’s brilliant improvisation but also his compositional genius in a way that hadn’t been exposed to this point.

Shorter has said that “Juju” was inspired by African chant, which it may well have been, but what is most striking about it is its use of whole tone sequences in the descending opening note, over huge block chords from McCoy Tyner. Tyner takes the first solo, and it’s striking how without Shorter’s melodic line and that whole tone scale how normal everything sounds, at least until the head of the melody comes back. When I first heard this tune, on the Blue Note Best of Wayne Shorter compilation sometime in my early college years, I was struck by the echoes of Coltrane’s sound. Listening now, many years later, there’s definitely the sound of Coltrane’s band, but Wayne’s soloing is a completely different thing. He finds different corners of the melody and scale around which to improvise but never seems to disappear into the music the way that Trane was doing in 1964. The incredible moment for me in this work comes near the end, where after two minutes of intensely rhythmic soloing, Wayne surrenders to the harmonic imperative and simply blows a trill, then returns to his solo with octave jumps and shorter phrases as though he’s catching breaths. But he isn’t surrendering to the dance, as the inversion of the melody he plays at 5:30 shows; he continues to play consciously through the whole work. An intense drum break from Jones separates Shorter’s solo from the final choruses, and even here Shorter doesn’t bring the piece to a neat close; in the last 30 seconds he’s found a new melodic pattern, and Van Gelder fades out the end as the band still explores.

“Deluge” opens out of time, but quickly pivots into a swinging minor melody that is pretty conventional… until Shorter’s solo descends its scale from the supertonic and we’re reminded that we’re in the presence of a harmonic genius. Tyner’s solo remains grounded in the original chords. For a player who was himself no compositional slouch we can hear the difference in their imaginations and approaches to the music at this stage, as Tyner improvises across chords and rhythm while Shorter thinks melodically across a wide harmonic range.

“House of Jade” opens with a meditative arpeggio that might have appeared on one of Tyner’s later Blue Note albums, but was actually written by Shorter’s then-wife Irene. When Shorter’s saxophone enters it returns us to the moment with a 16 bar minor key melody that then transitions into a series of held suspensions, played as delicately as possible. The reverie lasts even as Shorter and the band take the melody into a double-time section, then back into the slower reflection to close.

“Mahjong” opens with that greatest of gifts, a sixteen-bar Elvin Jones drum solo in which we get to hear his full harmonic and rhythmic command of his instrument. Nat Hentoff’s liner notes point out that the tune is structured in a way—four bars melody, “4 rhythm, 4 melody, 4 rhythm, 4 bridge-type melody, 4 melody, 4 rhythm … the 4 bar sections of rhythm without melody suggest players pausing to think of their next move.” Mostly, though, the piece gifts us another brilliant Shorter improvisation, particularly at the end where his descending scales taper into a crepuscular hush…

… which makes the impact of the opening run of “Yes or No,” probably the second best known of the compositions on the album after the title track, all the greater. While the form of Shorter’s melody is blueslike, we’re definitely not in the harmonic language of the blues; the tune arpeggiates around a major triad but then leaps the octave and drops a minor third down to the 6th, repeats the pattern, and then climbs up a minor scale and descends down a set of minor triads to return to the tonic. All those words aside, it’s an immensely memorable melody and one that, even with the minor colors in the last four measures of the tune, is upbeat and exuberantly happy. McCoy Tyner follows, picking up from Wayne in the middle of a chorus, and playing through the changes with a gorgeous light touch, only occasionally falling back on the heavy clusters of chords that mark so much of his playing through the rest of the album. Elvin Jones’ extroverted drumroll at the end puts the cherry on top of what is a delightfully rich sundae.

“Twelve More Bars to Go” is, as Shorter says, both a nod to the 12-bar blues form of the piece and a picture of “someone having a very good time, going around to every bar in town.” The portrait plays out through the solo, as Shorter injects an inversion of the harmonic pattern at the very beginning, as he says, “to picture a man, slightly intoxicated, who, as he tries to go forward, backs up.” There are intermittent pauses, long stretches of fluent playing, repeated ideas — it sounds as though Shorter’s narrator has been having a wonderful time. As have we.

Wayne Shorter wasn’t done recording outstanding music with JuJu. On Christmas Eve 1964 he went on to record Speak No Evil, and the following month began recording E.S.P. with Miles. All told, Shorter and the other members of Miles’s band were on track to make the 1964-1965 period one of the most fruitful in modern jazz recording. We’ll hear another album from one of the members of the quintet that was also recorded at the same time, with some of the same players, next week.

You can listen to this week’s album here: