Album of the Week, April 27, 2024

As McCoy Tyner continued on his post-Coltrane career, his version of the modal jazz that he had begun playing with Trane from the earliest days continued to evolve. We saw some of the developing hallmarks of the style with Expansions: use of minor modes, unusual percussion, and drones. These continue on Extensions, recorded by Tyner on February 9, 1970 at Van Gelder Studios in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, but not released by Blue Note until 1973, after he had already left the label.

Tyner brought to the sessions not only his compositional A game but an incredible band. Returning from Extensions were Gary Bartz, Wayne Shorter and Ron Carter; new members included his old bandmate Elvin Jones on drums, and another Coltrane—Alice—on harp.

Alice McLeod, born 1937 in Detroit, began her jazz career at an early age, performing on piano in Detroit clubs in the late 1950s and moving to Paris to study with the great Bud Powell. She married a jazz musician there, trumpeter Kenny “Pancho” Hagood, and had a daughter, but was forced to return to the States as Hagood’s heroin addiction worsened. She performed with her own trio and with vibraphonist Terry Pollard; she was playing in Terry Gibbs’ quartet in 1962-1963 when she met John Coltrane. They married in 1965, and Coltrane became her daughter’s stepfather; they had three children together. Alice joined Coltrane’s band in 1966 after McCoy Tyner’s departure and played piano in the quartet until Trane’s 1967 death. She encouraged Trane’s growing interest in spiritual matters from as early as A Love Supreme, and he encouraged her musical development, even ordering a full sized concert harp for her without her knowledge which was delivered after his death.

Alice Coltrane wasn’t the first to adopt the concert harp as a jazz instrument; others, notably Dorothy Ashby, pioneered the instrument in a jazz setting. But she was the first to bring its sound into spiritual jazz, where she denuded it of any classical affectations. The harp sound that she adds to the album evokes music from earlier traditions, including African and Middle Eastern, a connection reinforced by the album’s National Geographic inspired cover.

Together on Extensions, Tyner and Alice Coltrane conjured a jazz sound that took the hallmarks of Tyner’s spiritual jazz style and added an element of repetition, almost to the point of mantra, and groove. Trane had all but abandoned traditional meters by the time of his death, but the form of spiritual jazz that Tyner plays here is anchored in a constant heartbeat.

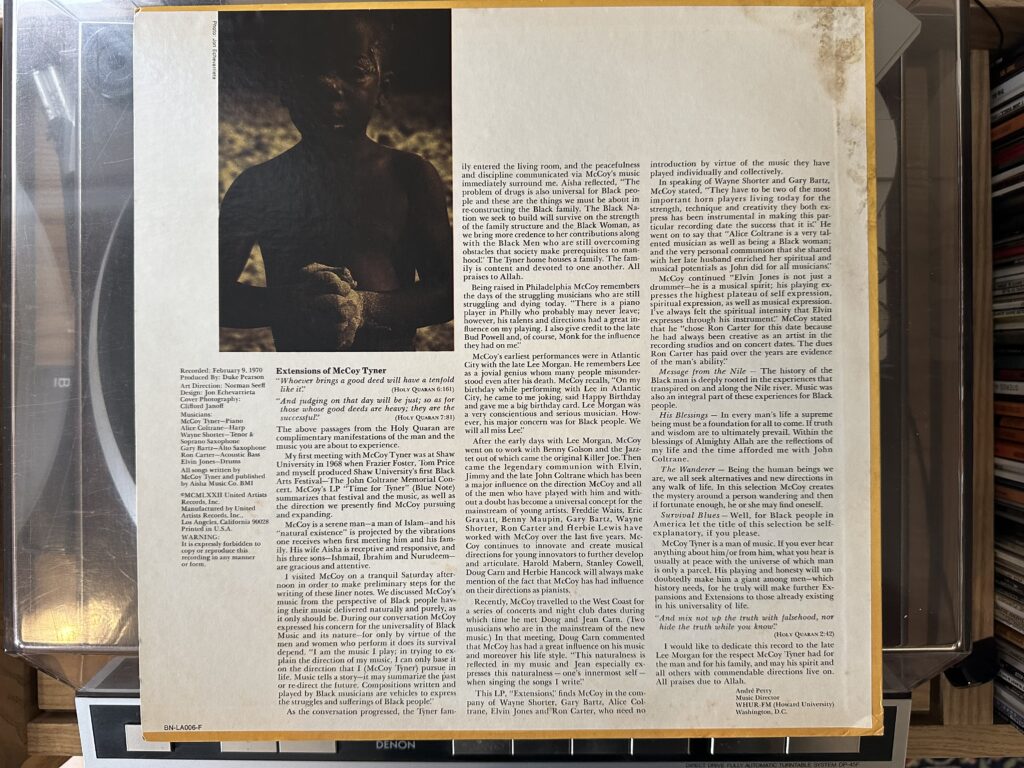

That heartbeat begins with Ron Carter, who opens “Message from the Nile” with a pulse on an open fifth. Alice Coltrane follows after four bars, adding harmonic complexity by bringing out the supertonic and seventh notes of the chord in her rhythmic harp patterns as Elvin Jones enters on cymbal and snare. Tyner enters, stating the melody with repeated, strongly rhythmic piano chords. Shorter and Bartz join at the second chorus, playing the melodic pattern in parallel fifths. The whole tune essentially consists of two tonal centers a minor sixth apart, and in each part of the tune the same melodic patterns are repeated four times, as if establishing a mantra for meditation; the static melodic and harmonic pattern still moves thanks to the strong rhythm established by piano, bass, drums and harp. Tyner solos, exploring the corners of the tonality established at the top, and then passes to Shorter, whose soprano saxophone echoes some of Coltrane’s melodic searching without dipping into the growled or smeared tones practiced by Trane. Those effects appear in Bartz’s solo as he returns over and over to the tonic. Alice Coltrane’s harp solo returns some measure of the opening ethereal meditation, underscored by a high-pitched wooden flute, uncredited but possibly played by Tyner himself (he was credited with playing the instrument on a subsequent Blue Note date). The whole thing is an active meditation, which WHUR-FM music director André Perry argued in the liner notes was influenced by the “history of the Black man … deeply rooted in the experiences that transpired on and along the Nile river.”

“The Wanderer” takes a more straightforward compositional approach and is the only track on the album on which Alice Coltrane does not appear. In contrast to “Message from the Nile,” the tune moves through eight chord changes in as many measures, the restlessness giving the tune its name. There’s a thematic connection to the prior tune, though, in the strong rhythmic pulse and in the playing of the theme in parallel fifths by the saxophones. However, there’s an abrupt gear shift about one minute in following the third statement of the melody, as Wayne Shorter takes off on a tenor exploration around the melody that’s underscored by Ron Carter’s running bass line. Carter indeed seems to find new tonal centers as he grounds the line in a sustained pulse on the tonic and the seventh. Shorter tapers off in a series of triple note runs, at which point Bartz picks up the solo torch in the alto that explores the ideas that Shorter was just playing with before returning to the melody, shifting it into a few different keys and then passing to Tyner. Tyner’s solo continues shifting the tonal center around until the players fall away and Jones wanders into several different rhythmic patterns, before transitioning back to the strong beat of the beginning as the band recapitulates the opening.

By contrast, “Survival Blues” begins with Tyner playing solo, an opening that seemingly straddles the spiritual jazz in which the record is centered with more traditional blues chords, even seeming to reach into some Duke Ellington inspired moments around the 30 second mark. At about the one minute mark, he settles into a strong rhythm backed by a repeated bass ground and supported by Jones in full polyrhythmic splendor, as well as by Alice Coltrane, who provides both chordal continuity and moments of chromatic accent. The tenor saxophone states the melody, which runs an octave via the seventh, three times before Shorter begins to shift things around, both chordally and rhythmically. His lines explore the entirety of the space around the melody before handing off to Tyner, who finds secondary rhythms and a second center of gravity around the fifth of the chord. Coltrane joins him on the second half of the solo, as she both picks up some of the secondary rhythms and reinforces the underlying chords with carefully chosen accenting notes in the upper octaves. Ron Carter takes a solo, accompanied by shaken sleigh bells, that walks the core rhythm around the entirety of the octave, finding unsettling tensions in the slide from the second to the third and down to the octave. The introductory melody returns before Jones takes an extended solo that explores the core pulse. The band returns, including Coltrane who performs an extended glissando into the restatement of the opening theme before Shorter returns once more to state the opening theme. (Bartz appears to have sat this one out.)

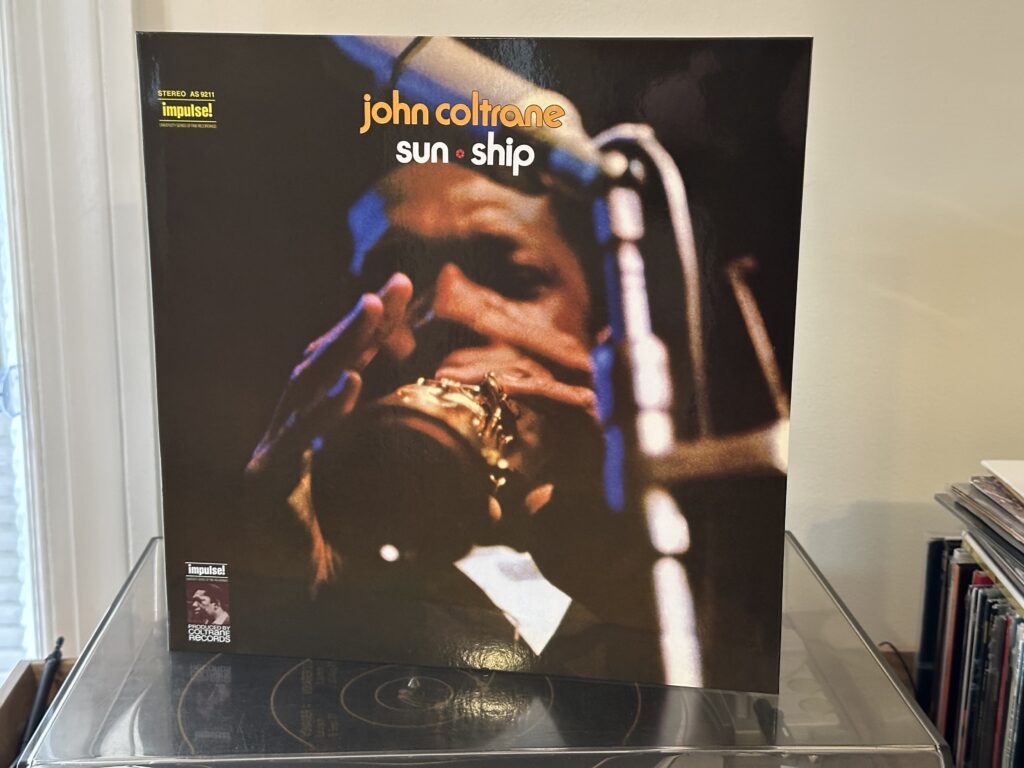

Coltrane brings that magnificent glissando back to open “His Blessings,” as Tyner explores the opening chord while Carter’s arco bass plays a melody that expands into a tremolo, Bartz pulses small fountains of sound, and Jones’ oceanic rolls keep things moving along. Shorter plays a line in the soprano saxophone that brings John Coltrane’s melodies on Sun Ship to mind while simultaneously calling back to In a Silent Way. Alice Coltrane takes a solo, performing glissandi in the upper strings while playing a melodic line with her other hand in the middle strings, over Carter and Tyner. Shorter returns for one more extended solo over a tremolo bass solo that hangs suspended on the fifth. If other tracks on the album call to mind some of Tyner’s earlier compositions, this one is unique, a spiritual meditation that seems to hang like a sphere in the air. The liner notes credit this as “the reflections of my life and the time afforded me with John Coltrane.”

In early 1970, Tyner was at the peak of his compositional and performing career, and Extensions reflects it. This was a peak period for his writing and performance that would continue even as he left Blue Note, a transition that delayed the release of Extensions for several years. But part of the credit for this album inevitably accrues to his players, especially Alice Coltrane. That debt becomes clearer when we listen to her work next week.

You can listen to the album here: