Album of the Week, February 3, 2024

John Coltrane appears to have taken the criticism of his avant-garde work in the early 1960s to heart. In fairness, being called “anti-jazz” cannot have been good for the tenor’s ego. But Trane was self-aware enough about his work, and conscious enough about his progression as a performer, to have taken a more deliberate step into a different sonic world on this album. Or, as he told critic Gene Lees (as told in the liner notes to this album) when he asked why the change in sound, “‘Variety.’ Meaning a change of pace. And perhaps he wanted to apprise [sic] those who haven’t discovered it [sic] that he can be lyrical.”

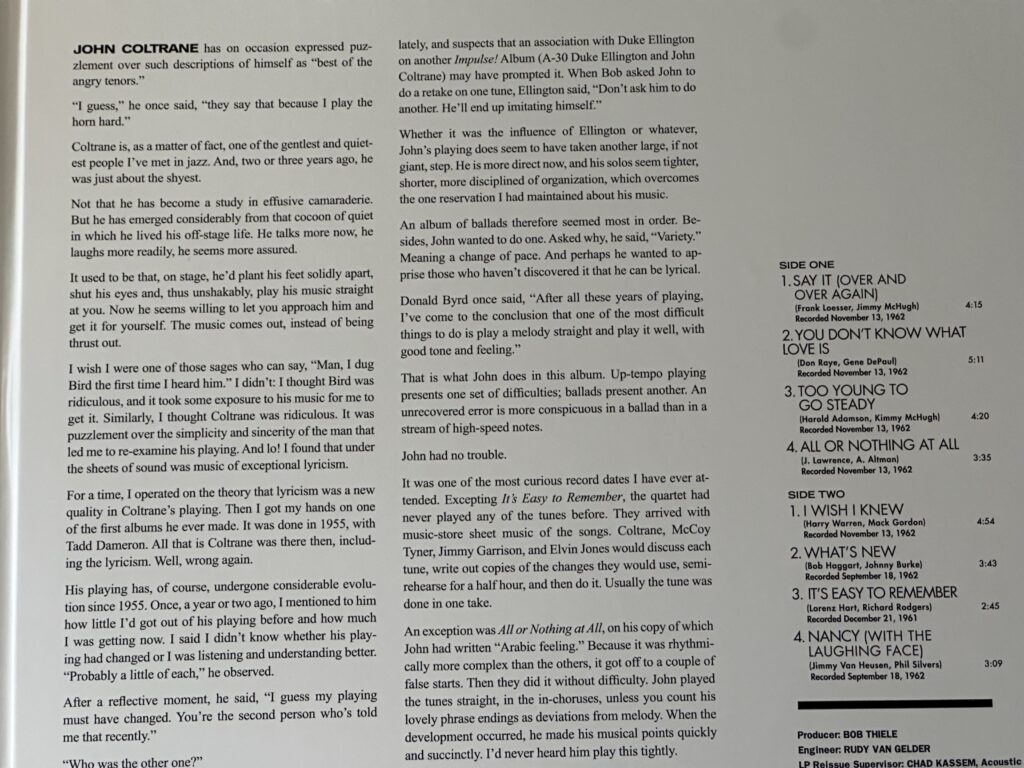

Whatever the reason, Ballads is about as lovely and straightforward a reading from the Great American Song Book as you’re likely to find. Recorded in three sessions beginning December 21, 1961, about six weeks after the final recordings at the Village Vanguard that yielded Live at the Village Vanguard and Impressions and still featuring Reggie Workman on bass, and continuing into late 1962 (with the classic quartet featuring Jimmy Garrison, McCoy Tyner and Elvin Jones), the sessions interleaved with recordings for other projects, including Coltrane, Duke Ellington & John Coltrane, and some of the studio recordings for Impressions. Legendarily, the quartet walked into the sessions with a pile of music-store sheet music for the songs, never having played any of them before. Overwhelmingly, the impression is of Coltrane treating his saxophone like a voice and his solos like song.

“Say It (Over & Over Again),” a Jimmy McHugh classic, sounds superficially in arrangement like the ballads we’ve just heard on McCoy Tyner’s solo albums, but listen closely and there are cues that Trane is still at the wheel. The suspensions in the pedal bass through the verse, the restraint of the group’s sound overall even as Tyner brings a gentle glissando through the middle of his solo, the opening feels tentative and even a little melancholy. But then comes the key change in the bridge and suddenly there are echoes of some of the soloistic choices on Coltrane’s Sound. The saxophonist’s solo trails off, as if in a reverie, and Tyner follows.

“You Don’t Know What Love Is,” by contrast, brings some of the energy in the reading of the head that Trane used in My Favorite Things. But while the vocal sound of the track is full and warm, he keeps the pyrotechnics hidden away in favor of a straightforward reading of the tune. Not to say it’s boring. The syncopation he brings in the major-key middle eight of the tune, the explosions from Elvin Jones’ kit, and most of all the modal rocking in the piano as the group transitions out of the head and into the first solo all place this in the lineage of “My Favorite Things” and “Greensleeves.” Trane’s solo gets more impassioned, bringing bursts of sound from Jones, but then he reels it back in on the final statement of the head, with only (only!) one final octave jump and descending arpeggio to hint at the pathos of the tune. By comparison, “Too Young to Go Steady” is a cheery, straightforward reading of the Jimmy McHugh tune made famous by Nat “King” Cole. Only Jones’ slightly wide-eyed double-time snare work hints at anything more than the tune itself. You’d never know the tune was written (by Gene DePaul, lyrics by Don Raye) for an Abbott and Costello film.

Jones kicks off “All or Nothing At All” with a full kit workout that leads into a modal bass line and comping piano chords. Lees’ liner notes indicate that Trane was trying for an Arabic feeling in this cover of the Arthur Altman tune, and there’s certainly more development in the solo, with hints of the “sheets of sound” glissandos at phrase ends and in the minute-long outro. But where earlier recordings might have had those glissandos climbing for the stars, here they seem to turn inward as the track gradually fades out. It’s another one where you get a sense of the Coltrane of “My Favorite Things” waiting in the wings, but he never quite steps into the spotlight.

Harry Warren’s “I Wish I Knew” gets a quiet and contemplative treatment. Both Jones and Jimmy Garrison are relatively restrained in their accompaniment, while Tyner shows his well-earned reputation for elegance in his brief solo. Trane plays a little with the time in the return of the head, but otherwise plays it absolutely straight. The finest moment of the arrangement might be the two arrivals of a new key in the coda, hinting that the band might just explore the tune forever if you let them.

Bob Haggart’s “What’s New” is given a full verse intro by Tyner playing solo, before Coltrane joins on the melody. While the overall tempo is subdued, Jones keeps just enough pots boiling on the kit that things continue moving into the solo, where Coltrane picks up the energy as well. The band ramps things down almost as quickly as they start. “It’s Easy to Remember (But So Hard to Forget),” a Rodgers and Hart classic, follows closely behind. The only track from that 1961 session on the record, and the only one featuring Reggie Workman, the sound is remarkably of a piece with the rest of the album. Trane perhaps incorporates a little more flourish into some of his playing in the middle chorus, but it’s otherwise a concise statement of the tune, given presence by an Elvin Jones roll of thunder at the end.

Jimmy Van Heusen’s “Nancy (With the Laughing Face)” was originally recorded by Frank Sinatra in 1944 and is named after his daughter, but there are no boots, made for walking or otherwise, in Trane’s treatment of the tune. Trane’s saxophone seems to breathe like a singer, achieving an almost vocal tone. Garrison’s bass is a subtle accompaniment throughout. The band picks up the energy a little in the second bridge, but ultimately closes the tune, and the album, as gently as it started.

Ballads accomplishes its goal of showing a different side of Coltrane. He trades flashy technique for constrained intensity and achieves a different kind of mastery of his instrument in moments like “You Don’t Know What Love Is” and “All or Nothing at All.” Compare the performance to some of Trane’s earlier ballad work, for instance on Lush Life—there’s many fewer notes here, saying just as much if not more. By subtracting some of the complexity of the earlier performances, Trane seems to gain depth and intensity in each of the notes he does play. We’ll continue in this vein with another album from his band next week.

You can listen to today’s album here: