Album of the Week, October 21, 2023

One thing I neglected to address in my review of Pearl Bailey’s 1957 recording A Broad was the double entendre in the title. That’s because I was saving it for the discussion of this week’s recording, which is basically one long series of double entendres after another. This, in fact, was Pearl’s primary career direction for many years.

Given her career start in vaudeville, Bailey’s devotion to the art of the subversively sexual song is unsurprising. This is, after all, an art form that had as its flip side the burlesque, that originally comic art form that eventually became more and more risqué. Still, the songs on this collection are more mockingly suggestive than explicit, in keeping with Pearl’s style. As she noted in a 1965 interview:

She believes an entertainer can express himself through more subtle means. Anyone who has seen a Pearl Bailey performance knows she gets a point across with a lackadaisical shrug of her shoulders, a lazy wave of the hand, or a roll of the eyes.

She demonstrated for Belli by singing, “Row, Row, Row,” the tale of a young man who rows, rows, rows his boat until he and his girl friend are alone . . . at last!

“Honey, I don’t have to spell it out,” Ms. Bailey said as she interrupted the song to make a point with Belli. “The audience knows this here fella ain’t rowing for the fun of it.”

This kind of treatment, she says, is performing.

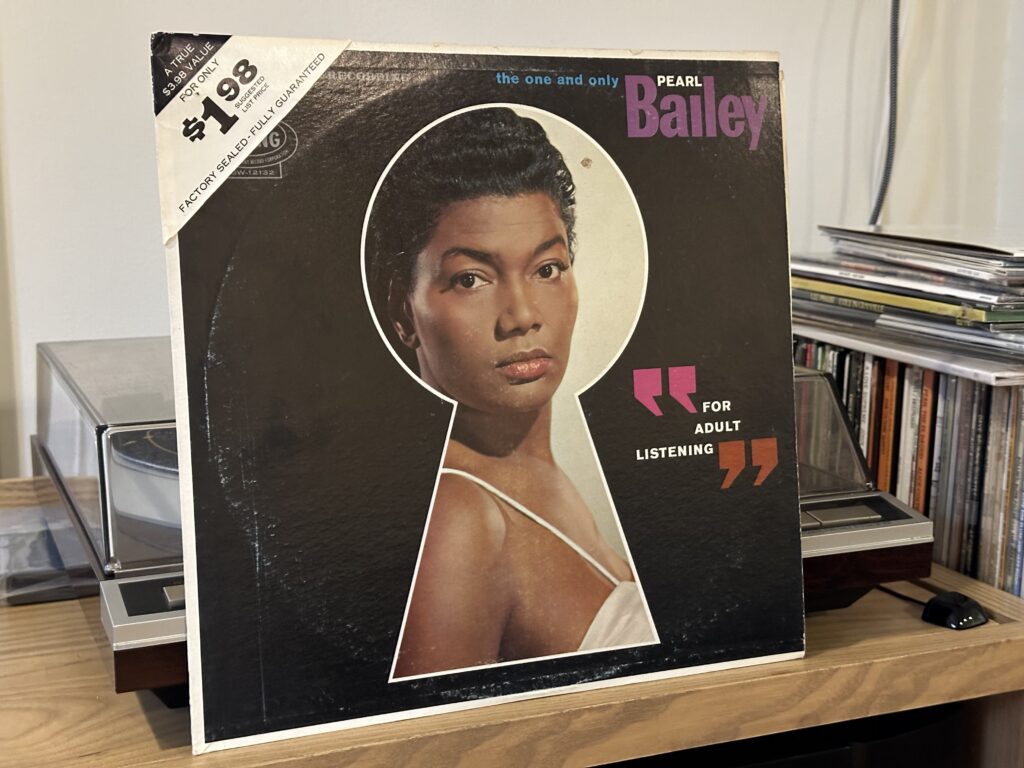

So Pearl performed, across a series of late 1950s and early 1960s albums, with titles like Sings for Adults Only, Naughty but Nice, More Songs For Adults Only, and today’s record, released in 1962. Mildly risqué the lyrics might have been, but the production values had climbed substantially since the days of A Broad, with none other than swing arranger Don Redman conducting the orchestra. And most importantly, the quality of Pearl’s performance and her choice of material—both broad and sensitive, uptempo and ballad—make this a record worth seeking out.

The record starts with “A Porter’s Love Song to a Chambermaid,” by Andy Razaf and James P. Johnson, which seems designed as a catalog of low-intensity come-ons. “I will be the oil mug/if you’ll be the oil” is a couplet whose overt implications are lost to history but whose covert meaning is clear enough; likewise “I’ll be the washboard/if you’ll be the tub,” “I’ll be the shoe brush/if you’ll be the shoe,” and so forth. But Pearl invests all these couplets with all the sly energy she has, and it plays.

She pulls off the same trick on “A Man is a Necessary Evil,” where after cataloguing the faults of a man, she allows “But a man is a necessary evil/especially on a cold, cold night.” Her wry energy continues to power “The Gypsy Goofed,” as she faults the fortune teller for her man’s faults: “She told me that you loved me and said that you’d be true, but darlin’, she was wrong because you loved somebody new.”

Not all is fun and games on the album. “My Man” is a dark chanson that feels like it could have been sung by Edith Piaf, save for the English lyrics: “Two or three girls has he/That he likes as well as me/But I love him!/I don’t know why I should/He isn’t good/He isn’t true/He beats me too/What can I do?” “You Waited Too Long” flips the script as Pearl tells her erstwhile paramour, “You waited too long/and now my heart is singing someone else’s song.”

“Sweet Georgia Brown” brings the tempo back up, with Pearl hinting at the secret of Georgia Brown’s charm: “They all sigh, want to die/For sweet Georgia Brown/I’ll tell you why/you know I don’t lie … not much…” “Easy Street,” by contrast, is a languid ballad that extols the virtues of relaxation: “When opportunity comes knockin’, you just keep on rockin’, ’cause you know your fortune’s made.”

“I Can’t Rock and Roll to Save My Soul” is, ironically, arranged as a rock song, opening with Pearl’s admonition to “oh, play that guitar!” She notes, “I am never known to slumber when they play a rhumba number, but I can’t rock and roll to save my soul.” There is a certain regrettable sameness about the lyrics of songs performed by big band and Sinatra era singers regarding the onslaught of Elvis, but Pearl sells this one through sheer exuberance.

“There’s a Man in My Life,” a slow ballad by Fats Waller with George Marion Jr., regretfully notes, “There’s a man in my life, responsible for/the kind of life I lead/He’s the talk of my heart/When thoughts of him start/I find myself all a-tremble like a wind blown reed.” The quiet despair in her voice is offset by the following track, “Everybody Loves My Baby,” which confidently declares “my baby don’t love nobody but me.”

We return to the suggestive with “There’s Plenty More Where That Came From,” which asks, “Do you like my huggin’? Do you like it, hon? Well, if you like my lovin’ and my kissin’ and my huggin’, come and get it, son, ’cause there’s plenty more where that come from.” The uptempo songs continue into the finale, “That’s My Weakness Now,” in which Pearl declares, “He’s got eyes of blue/I never cared for eyes of blue/but he’s got eyes of blue/and that’s my weakness now.” At the end we hear the hint of naughtiness: “he likes a family/well, Pearl’s never liked a family/but this boy wants a family/so that’s my weakness now.”

Pearl wasn’t destined to do suggestive material forever, even material as mildly suggestive as this. She was also performing on Broadway, and her 1967 all-black cast performance in Camelot opposite Cab Calloway played to sold-out houses and earned her a Tony Award. She was still in that renaissance when I first saw her perform in 1978 on The Muppet Show. She would write four books, be appointed a special ambassador to the United Nations, and complete a degree in theology at Georgetown University before her death in 1990. As a performer, she had impeccable taste and an indomitable wit, and you can see both in her performance with Sgt. Floyd Pepper from that Muppet Show episode.

You can listen to today’s album (in a later, retitled reissue) here:

I love everything about this.