Album of the Week, January 7, 2023

Bill Evans—whom we last saw providing compositions and historic accompaniment for Miles on Kind of Blue—was putting things back together. On June 25, 1961, he and his trio—Paul Motian on drums and Scott LaFaro on bass—performed a legendary set at the Village Vanguard club in New York City, from which the famed albums Live at the Village Vanguard and Waltz for Debby were drawn. The trio was making a name for Evans’ innovative, dreamy compositions and for the unusual equality of voice among the three players in the trio, particularly with Scott LaFaro’s bass playing. Then, on July 6, 1961, LaFaro was killed in a car crash on US 20 in Seneca, New York. Evans was bereft, playing nothing but his and LaFaro’s version of “I Loves You, Porgy” for days and pausing all performances.

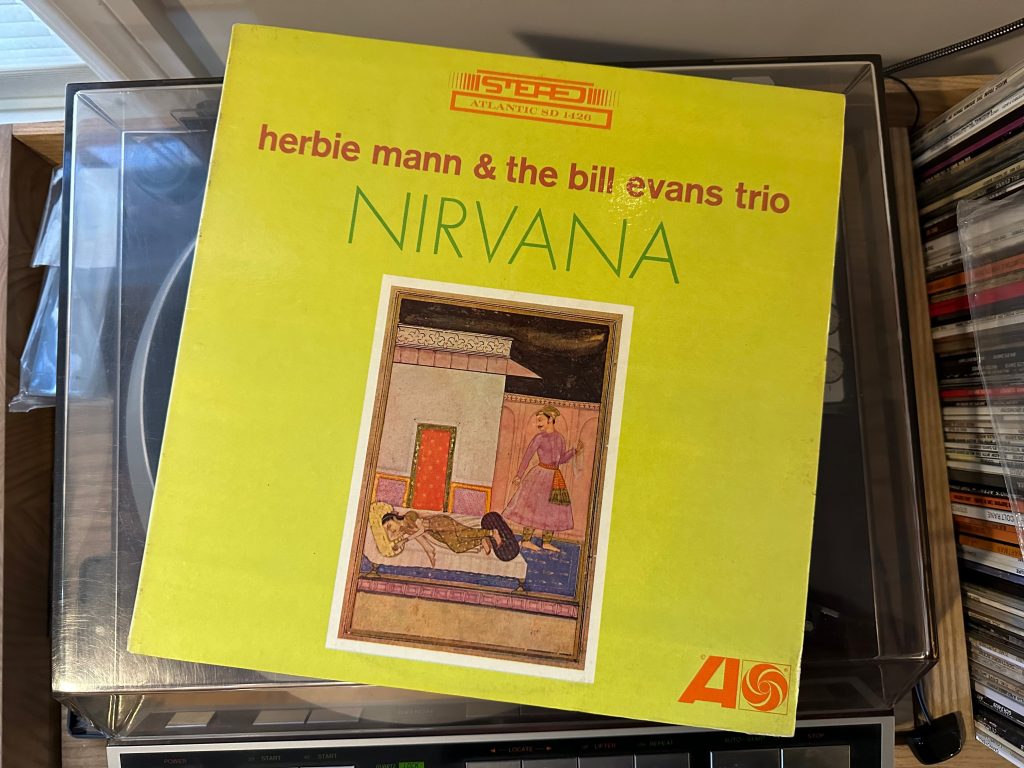

By December 1961 Evans was recording again. Spurred by his producer and Riverside Records founder, Orrin Keepnews, he put his trio back together, this time bringing in the bassist Chuck Israels. Before the trio recorded any sessions for Riverside, though, they found themselves in the Atlantic Records New York studios December 8, 1961 with producer Nesuhi Ertegun and flautist Herbie Mann.

If you have been on the Internet for any length of time you’ve seen the listicles of bad 1970s album covers. One, Push Push, is especially memorable, showing a balding, shirtless man in a hairy-chested slouch with a flute over his shoulder. That’s Herbie Mann. But before he was recording (pretty good!) jazz-funk albums with eye-bleach-worthy covers, he was a straight ahead post bop jazz soloist and composer. So while the pairing of the two might sound odd on paper, on vinyl it makes a lot more sense.

The opening track, “Nirvana,” is a Mann original, but it opens up sounding a lot like a Bill Evans composition, as the trio introduces the chordal progression almost at a whisper, Evans exploring modes around the chords as Israels’ bass quietly marks the fifths. When Mann’s flute enters it’s as though he was whispering too, and his melody provides Chuck Israels with the moment to start exploring the tune independently. The dialog among the players is sensitive and you can almost see them listening to each other and nodding quietly as each introduces new ideas. The tune unfolds like breathing.

The mood continues with “Gymnopédie,” one of the rare jazz covers of the second of the Erik Satie compositions, instead of the more commonly encountered first. The trio introduces the theme and Evans and Mann take turns essaying the melody of the composition. It’s a gentle meditation and true to the original composition, which depending on your inclination is either refreshing or slightly stultifying. Interestingly, though it sounds like a continuation of the first track, “Gymnopédie” and the final tune “Cashmere” were actually recorded at a different session in May of 1962.

“I Love You” changes things up, with the players digging into the faster tempo of the Cole Porter song and Mann’s flute ringing in a higher register. On the second chorus, Evans drops out and we hear just Mann, Motian and Israels, which seems to spur Mann’s improvisatory muscles. By the time the players reach the end of the tune, all are fully engaged, with Israels’ stretto in the accompaniment no less exciting than his solo passage, one of only two on the record.

“Willow Weep for Me” is back in ballad territory, and here the weakness of the record reveals itself: Herbie Mann is not that compelling a ballad player. He largely sticks to the melody or to very close improvisation around it, and while he tries to find the bluesier corners in Ann Ronell’s legendary tune, it’s ultimately not a compelling exercise. Evans finds more interesting things in the melody but ultimately this track is a little flat. “Lover Man” is better. The tempo is up just a touch, but more importantly Mann is more engaged, his improvisation and statement of the melody more compelling.

“Cashmere,” closing the album, is another Mann original and the trio digs into it, finding a slightly off-kilter syncopation in the accompanying line under Mann’s first statement of the melody. Mann’s subsequent improvisation picks up the syncopation and makes it central to his interpretation of the tune, and when he hands it back to Evans the latter’s chorus is sprightly and sly, zigging from corner to corner. Israels’ solo (here’s the other one!) digs into the silence between the melody lines and also into the syncopation, trying a one-note variation of the syncopation pattern over three bars as though leaning into the groove. His solo is supported by Motian’s unshowy but brilliant drumming, which quietly anchors each pulse of the entire album. The band’s returning statement brings the tune through several modes before closing on a final suspension.

Mann and Evans wouldn’t record again, but Evans would go on to make some essential records with his trio. We’ll hear some of them soon, but first we’ll hear another unusual record in his discography that he began recording between the December and May dates for Nirvana. Come back next week for more on that record.

You can listen to this week’s album here: