Album of the Week, October 22, 2022.

The hazard of going alphabetically through a large collection of music is that sometimes you can’t see when you are about to step on a land mine. That’s what Dixieland, and the Dukes of Dixieland, represents in a collection of jazz music: to put your foot down here is to step around three or four land mines all at once, or risk them blowing up on you.

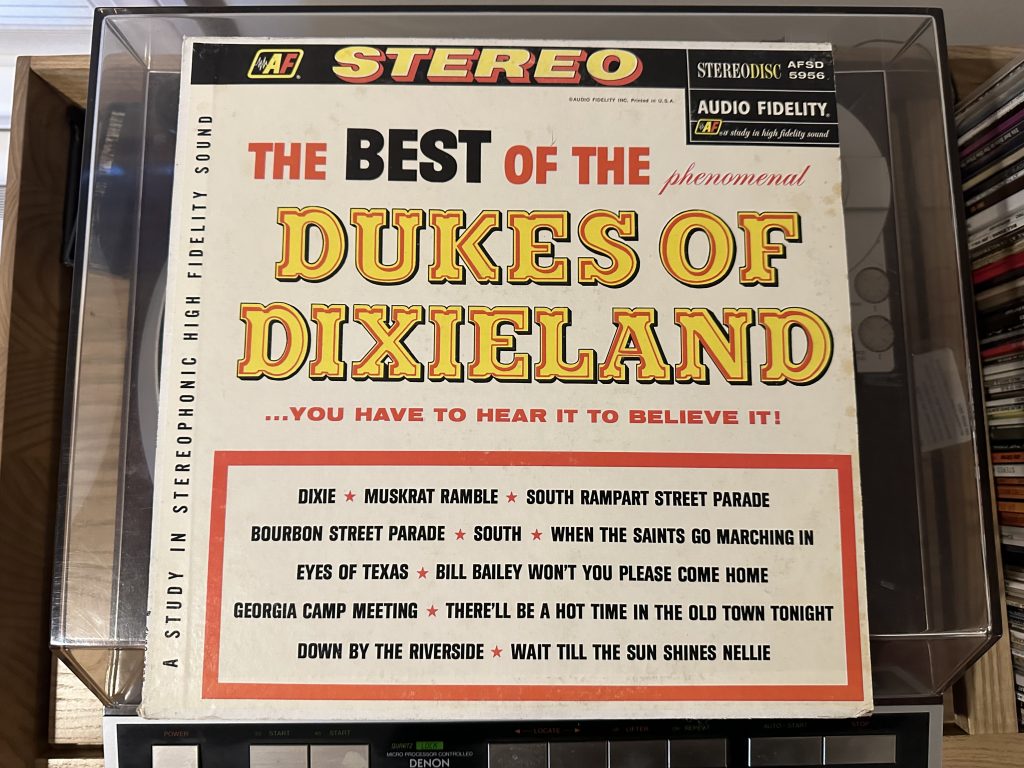

Let’s start with the facts: The Dukes of Dixieland were founded as an old time jazz revival band in 1947 by brothers Frank (trumpet) and Fred (trombone) Assunto with their father Papa Jac on trombone and banjo. Originally called the Basin Street 4, then 5, 6, and so on, they changed their name after going on tour with Horace Heidt and his Musical Knights, a big band radio and vaudeville circuit performer, in tribute to their home city and its tradition of jazz royalty—thus becoming the first Dixieland revival band. They recorded the first ever stereo record, released in 1957 on the Audio Fidelity label. They recorded several albums on which they backed Louis Armstrong. The Assunto brothers died in 1966 (Fred) and 1973 (Frank), and the name (if not the remaining performers) was picked up by producer John Shoup under disputed circumstances, with the new group, called the DUKES of Dixieland, apparently under the belief that the law is case sensitive, continuing to perform to this day.

So, the land mines: old-time jazz revival; Italian immigration in New Orleans; white appropriation of black culture; and of course disputed legacy band history (fair warning: I’m not getting into the arguments about the name). Let’s, for the moment, take those as stepped around (though we may find ourselves treading on one or more of them again soon). The question is: could they play? And the answer is: yes, but with considerably less swing and more self-consciousness than the men whose music they were preserving.

The sound overall of the record is precise, cleanly recorded, and well articulated. It’s all a little too careful, a little too on the nose. But there’s also a pleasure of a particular kind in hearing this music played carefully and well; what it loses in spontaneity and passion it gains in clarity. Tunes like “South” are played competently in their slow tempo, without ever risking taking off.

“Down By the Riverside” fares better, with the clarinetist keeping some heat under the the group as they move briskly through the arrangement. (One challenge with this recording: there isn’t a good sessionography, so I’m forced to guess at the identity of players who weren’t the Assunto family.) Indeed, the rule of thumb for quality on this record seems to be “the faster the tempo, the better the music,” as the opening number, “South Rampart Street Parade,” demonstrates.

So, about that appropriation thing. Generally, I don’t lean too hard against musicians who play in a tradition that isn’t their own, but as a white Protestant who sometimes sings gospel or South African music in church, I’ve learned to be careful about how I perform. There aren’t a lot of rules other than “be sensitive.” I’m therefore forced to look askance at a few numbers on this recording, including the interpolations of 32 bars or more of “The Flight of the Bumblebee,” “There’s a Place in France…” and “Dixie” in “When the Saints Go Marching In,” and the presence of the song “Dixie,” at all.

There’s a great story that Nat Hentoff tells about watching the Dukes record one of their sessions with Louis Armstrong:

“Dixie” was proposed as the next tune. Louis began to read the lyrics, but stopped, chuckling. “No, I can’t sing that. The colored cats would put me down.”

Nat Hentoff,

Nevertheless, that session did feature an instrumental version of “Dixie,” and Hentoff has written, “Hearing ‘Dixie’ with Louis leading the way, I was reminded of Louis’ uncompromising statement about Little Rock and also of the student sit-in leader I had met a few weeks before this session. I also remembered a white Southern historian who was proud of the sit-ins and said, ‘These students are also Southerners, and they are being true to the best Southern traditions of self-assertion and courage.’ ‘Dixie’ will never be the same again.”

Unfortunately that isn’t the version of “Dixie” on this record, which doesn’t feature any of the collaborations with Louis Armstrong. So we’re left with a group of white Southerners playing the song that begins “Oh, I wish I was in the land of cotton…”

Which brings me to the point about appropriation and immigration. What’s really interesting about the music of the Assuntos and the band they assembled is that it recapitulates the journey of Italian Americans to New Orleans. That there were Assuntos in the Big Easy at all was a direct consequence of the American Civil War, and the resulting collapse of the labor “market” in the South — if you’ve been an enslaved laborer all your life, when freedom comes along you’re unlikely to want to work in the places that enslaved you, even for pay — as well as of the Italian Risorgimento and the destabilization of the Southern Italian economy that followed.

While Northern Italy had factories and could offer good paying jobs, southern Italy (including Campania, from which my in-laws immigrated) and Sicily, home to the Assuntos and thousands of others, was left in poverty due to the continuation of the peasant labor system under absentee landlords. So planters in New Orleans ended up advertising in Sicily for workers, and many emigrated, leading to such a concentration of Italian Americans in New Orleans that at the turn of the century the joke went that the French Quarter ought to be renamed. And the immigrants picked up the culture of the place, including its music.

And ironically, the place picked up their music as well. Among the musicians in the Original Dixieland Jass Band, credited with releasing the first commercial jazz record in 1917, was Nick LaRocca, a Sicilian cornetist. So it appears that Dixieland was even more of a New Orleans melting pot than is normally known. But the all-white Dukes were not a good representation of that melting pot, by any stretch. There were other revival groups that managed to achieve a better blending of the streams of immigration and culture in the city, and eventually in this column we will get to one of them.

Where does this leave us? The common thread between LaRocca and the Assuntos lends resonance to the Dukes’ revival of the sound in the 1940s. And there’s no denying the craftsmanship of the bands featured in this best-of. In the back of my mind, though, every time I listen to a Dixieland record is the knowledge that this was throwback music made in deliberate rejection of the bebop jazz emerging from the black jazz musicians of the time, and that is why this admittedly well-made record doesn’t get much play in my house.

You can listen to the record here: