We laid my uncle to rest yesterday beside his wife, my aunt Alene, in their plot in the family’s corner of the mountain cemetery where my grandparents, my Aunt Jewell, my great-grandparents, and my great-great-grandparents lie.

It was a large service, in Asheville’s First Baptist Church, full of (almost entirely) masked mourners whom I knew from my uncle’s stories, or his get-togethers at his pond, or from the wild game dinners I attended a few times that were held in his name as a fundraiser for various outdoorsy causes. But the center of it all was his story.

The story of a boy who was so shy he hid from the mailman, who trained himself to be the life of the party. Who had a frank and open face until a baseball flattened his nose (and convinced the county high school to invest in protective gear for its high school baseball catchers). Who stood with such straight and perfect posture that they called him String, until a training accident in a tank sent a recoiling 90mm gun into his back and side, leaving him with a limp and perpetual back pain that sent him home from the Army. Who was going to be his father’s heir in scientific farming, until the accident made him seek another career—a career that his second cousin, who was the political kingpin of Madison County and his lifelong quiet opponent in a family feud rooted in a land deal, told him would never be near his home. Or, as my Uncle would say, “When I come out of service, my good kinfolks, Mr. Zeno Ponder, sent word to me by my first cousin, Marvin Ball, that he’d see me in hell before I’d get a job in Madison County.”

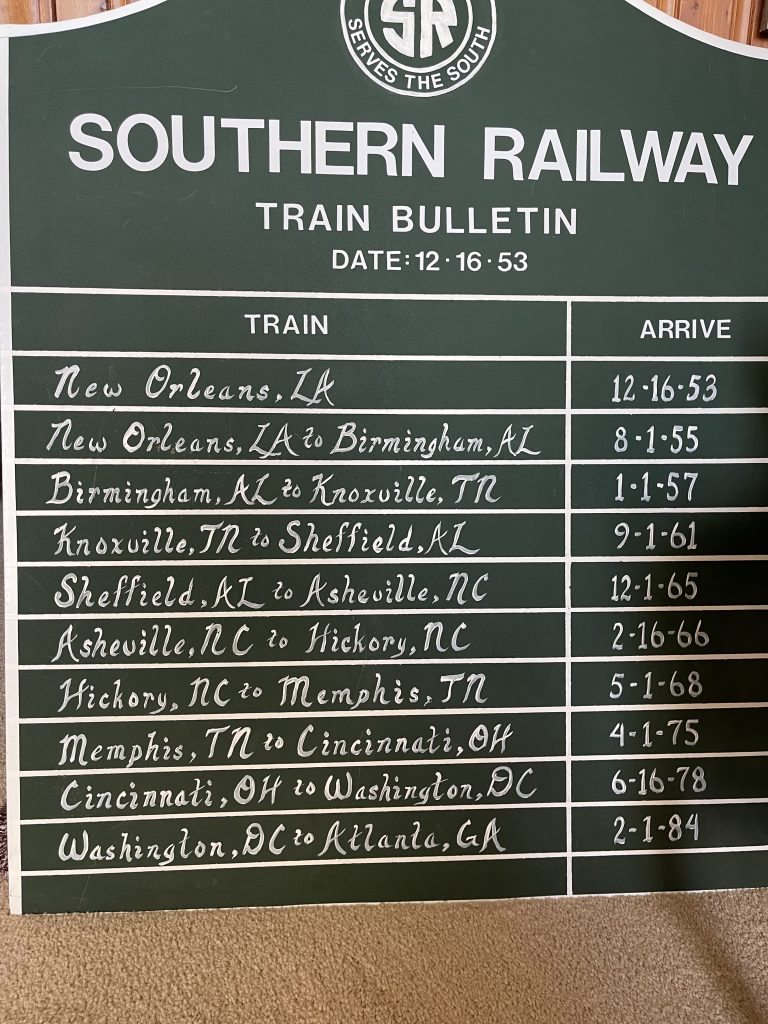

Who was sponsored for a job with Southern Railway by famed lawman Jesse James Bailey. Who, thanks to an early job as bodyguard for railroad executive and later Southern Railway president D.W. Brosnan, followed that career through eleven Southern cities and through multiple promotions until he retired as chief of railroad police. Who managed diplomacy with the old mountain gift for giving: small favors, “pettin’ pokes” with fresh produce, country sausage, or suspiciously clear Mason jars. Or by throwing enormous all-day-long barbecues. Or by taking you hunting. Whose gift of diplomacy built a network that showed up, in force and in masks, yesterday.

Who, when he retired, papered the walls of a study in his home on the old family farm with certificates and plaques: certified Railroad Policeman in Indiana. Certificates of appreciation from the North Carolina Sheriff’s Association, the Drug Enforcement Administration, the office of the mayor of Soddy-Daisy, Tennessee, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, the Secret Service. Honorary Illinois state trooper. Honorary chief of police in Hickory, North Carolina. Honorary assistant Attorney General in Alabama and Georgia. Honorary Lieutenant Colonel, Aide de Camp, Governor’s Staff in Georgia. Honorary Lieutenant Colonel and Aide de Camp in the Alabama State Militia. Honorary colonel and Aide-de-Camp in the Fairfax County Police Department. Kentucky Colonel. North Carolina Order of the Long Leaf Pine. Photograph with United States Senator Strom Thurmond. Christmas card from Barbara and George H.W. Bush. Congratulatory letter from Vice President Dan Quayle. Keys to several cities, including the key to Washington, DC presented by Mayor Marion Barry. Signed and framed copies of the Crime Control Act of 1990 (S.3256), which granted railroad police the power to enforce the laws of the jurisdiction in which they were operating, and which was passed largely on the strength of his diplomacy.

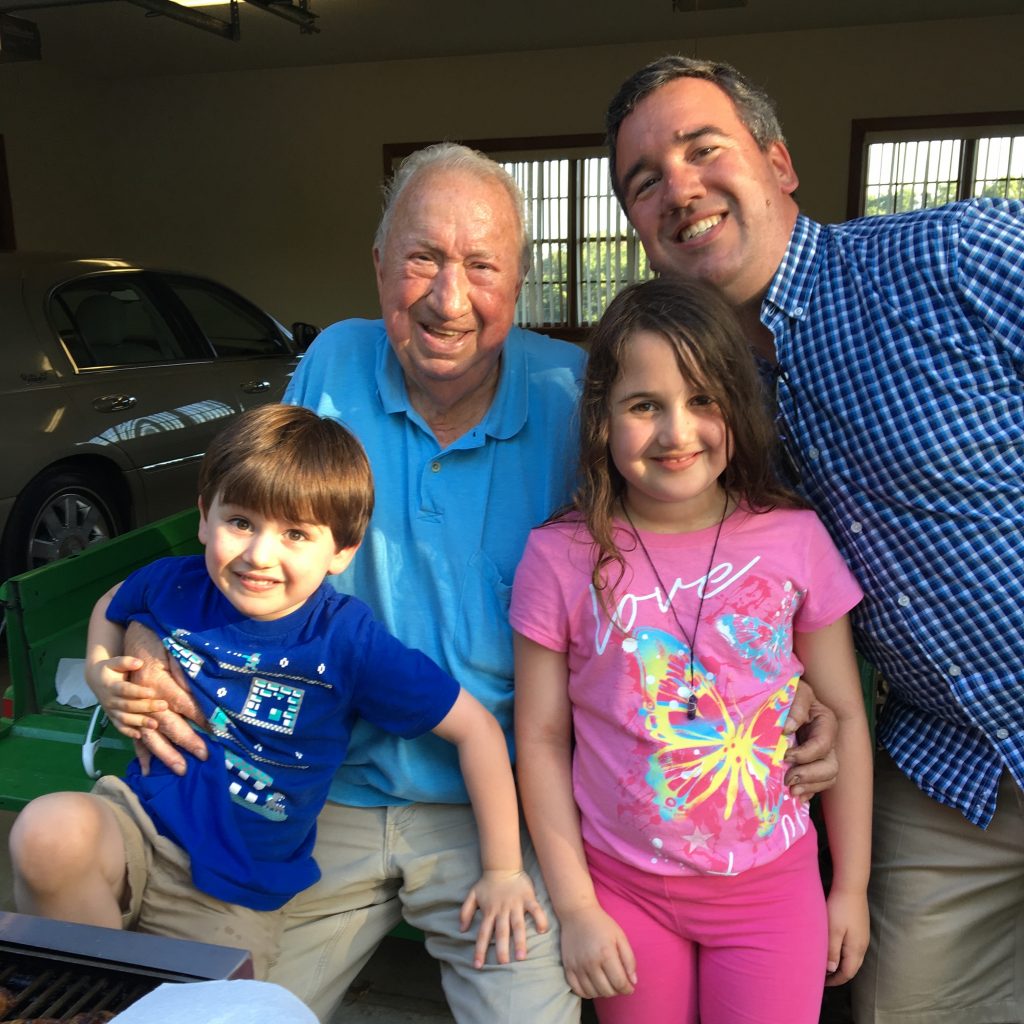

And who then promptly ignored that study, except to show visitors who asked, preferring to sit on his porch and watch the mountains, or down by his pond and soak in the silence. Or to take his grandchildren down the bumpy road to the pond on the Gator.

Because in the end, he was a man of enormous accomplishment for whom family was not only the most important thing, it was everything.

Godspeed, Uncle Forrest. You will be missed.