The CD Project proceeds apace; yesterday I finished ripping all my John Coltrane CDs to Apple Lossless format. As I looked at each disc in turn, annotating the files with session notes and musician info, I found myself drawn into memories of my self-education in jazz.

Growing up I listened to nothing but classical music until I was maybe 12 years old, when I discovered the Police—angry yet mannered, literate rock. At the time I wasn’t totally comfortable with the angry part, but I latched onto the mannered part. Listening to Sting felt rebellious but safe. A big part of that, particularly in the subsequent solo records, was the jazz influence. I decided I needed to learn more about jazz, and so I started at the logical jumping off point of Branford Marsalis, who at that time was playing with Sting.

Exploring jazz through Branford—a young player who was trying to establish his own identity but who provided few direct links back to the old tradition, simply because he generally only played his own compositions or a few standards—was difficult. But I liked what I was hearing, the interplay of the horns with the drums, and decided I needed to go deeper. By this time it was 1988 or 1989 and Bono was name-checking John Coltrane and A Love Supreme on U2’s grandiosely overblown Rattle and Hum—which naturally I also loved. (I was 16. Whaddaya want?) So I went out and got a copy of the pivotal Trane album.

I wish I could say that I was immediately blown away, but the truth is it took some time. There were things about the record that I thought were cool—the chants and the blazing solos on “Resolution,” made my hair stand on end. But I didn’t really get the modal melodies and couldn’t appreciate the extended drum solos at the heart of the piece. But I kept listening.

In another year or so, I was a first year at UVA, and shoring up my insecurity and loneliness with CD shopping at Plan 9. I desperately wanted to be cool and to be listening to things that no one around me was, and so I spent a lot of time spelunking throught the jazz racks, anchored to the few artists I knew anything about, which at that point consisted of Trane and Branford (and, somehow, Thelonious Monk—but that’s another story). I had no education, didn’t have the sense to start listening to jazz radio, so I used the copy on the back of the CDs to decide which ones to take home. This brought me to the Prestige and Fantasy releases (the so called “Original Jazz Classics”), which inevitably contained review capsules on the back cover of the CD with raves or claims of “instant classic.”

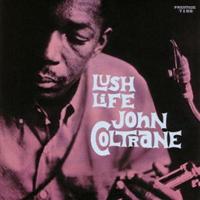

And that was how I came to pick up Lush Life: it was the Coltrane Prestige recording that had the highest ratings and the most stars on the back.

I took the disc back to the dorm and started listening. My then-roommate Greg was in the room and we soon were both listening: to the tremendous blown run that begins the album and “Like Someone in Love,” to the percussive experimentation of “I Love You” and the walking bass of “Trane’s Slo Blues.” And then the title cut, introduced by Red Garland’s piano followed by perfect choruses by both Trane and Donald Byrd. Partway through Byrd’s second chorus, Greg turned to me and asked, “How do you find this stuff?”

I wish I could have told him the truth, but I think I just mumbled something about being lucky.

I went on over the next few years to discover the rest of Trane’s work and to branch out into Miles, avant garde jazz, and the great blowing sessions of the 50s. I’ll be digitizing all of it in the weeks to come, but I think that none of the tracks will be as often as the five tracks from this set. I can’t even guess how many other versions of “Lush Life” I’ve found over the years (at least not without sitting in front of my home computer, though I can think of versions by Roland Hanna, Bobby Timmons, Joe Henderson, Duke Ellington (of course), and Johnny Hartman in a subsequent date with Coltrane), but this one remains the gold standard.